In his all-time classic novel Ivanhoe, Sir Walter Scott frequently refers to “Prince John and his friends”, but only a few are named. The novel is actually set in the period a decade and half prior to Magna Carta, when John was acting as regent for the real king, his brother Richard the Lionheart, who was away in Palestine, fighting the Third Crusade.

Shakespeare’s King John (one of his worst plays) is set in John’s actual reign as king. Shakespeare was more sympathetic to John than Scott has been. Here we present a list of men, culled out from both fiction and from non-fictional accounts, who could have aided and advised John.

The tallest among them was, without doubt, William Marshal, 1st Earl of Pembroke. Often called the “greatest knight that ever lived “in England (the eulogy came from Stephen Langton, leader of the rebel camp), Pembroke can be best likened to Bhishma of Mahabharata, a man who was caught between his sense of justice and his sense of duty. He also figures in the Shakespeare play.

The real William Marshal, who lived from 1147 till 1219, was an Anglo-Norman soldier who served four kings—Henry II, Richard I, John and Henry III, and was regent to the last named.

Impressed by his illustrious military career under Henry II, King Richard I included Pembroke in the council of regency, tasked with helping Prince John administer the kingdom when he (Richard) went for the Crusade in 1190. Pembroke aided John initially, but when he realised that John was now going against the interests of the real king, Pembroke joined the rebels. Richard rewarded him with titles and estates, including the earldom of Pembroke.

But, when John ascended the throne upon Richard’s death, Pembroke served him loyally. He fell out with the king in 1199, but was taken back into favour in 1212. He remained loyal throughout the hostilities that led to Magna Carta, and throughout the First Barons’ War.

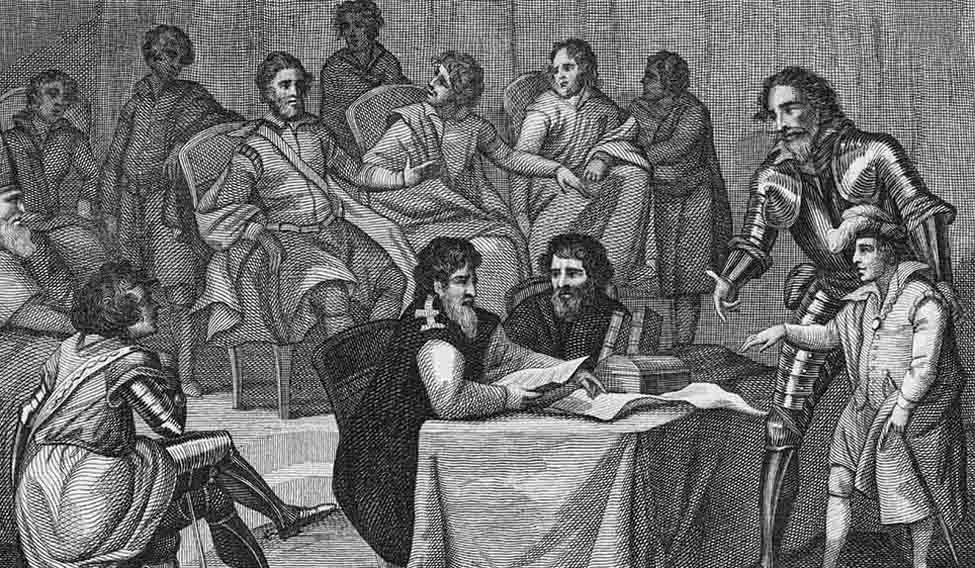

John took ill in 1216, and when he realised that his end was near, it was Pembroke whom he called to his deathbed and entrusted the job of ensuring that his nine-year-old son Henry succeeded him. The noble Pembroke made a solemn promise, and kept his word. He took the young Henry III under his care and acted as his regent.

Pembroke was one of the greatest statesmen of his time, known for his military prowess, diplomatic skills, administrative acumen, loyalty and chivalry. In 1217 he reissued Magna Carta, in which he is a signatory as a witness.

In March 1219, when he realised he was dying, Pembroke summoned a council of knights and bishops to ensure that the regency would be passed into the loyal hands of papal legate Pandulf Masca, instead of any other bishop or baron whom he did not trust. The great earl died, after fulfilling every word of honour he had given to his king, on 14 May 1219 at Caversham, and was buried in the Temple Church at Strand in London, where his tomb can still be seen.

Aubrey de Vere, 2nd Earl of Oxford and hereditary Master Chamberlain of England, was reputed as the “evil counsellor of John”. But it is doubtful whether the adjective ‘evil’ is appropriate. Like Pembroke, Oxford served his kings loyally.

He was with Richard in France and even paid 500 marks towards the ransom being collected to get Richard released from captivity. Later, he served John, too, faithfully. When the Pope put England under Interdict and excommunicated the King, he went to Dover to represent the King’s case before the Pope’s representatives. Oxford died in 1215, a few months before the barons forced John to sign Magna Carta, whereupon his brother Robert de Vere succeeded to the earldom of Oxford. But, Robert joined the rebels.

Another great noble who served John loyally was William Longespee, 3rd Earl of Salisbury, who also figures in the Shakespeare play. The real William Longespee (Latin for Longsword; so named because of his great size and the large weapons he carried) lived from 1176-7 to 1226. Salisbury was the illegitimate son of King Henry II, and, thus, half-brother to Richard and John. Richard married his half-brother to a great heiress, Ela of Salisbury.

During John’s reign, Salisbury held several high offices. In 1213, his fleet defeated the French at the Flemish port of Damme. In 1214, he went to help John’s friend Otto IV of Germany to invade France, but was captured by the French.

By the time Salisbury returned to England, the barons had been rebelling against John. In the civil war that took place the year after the signing of Magna Carta, he led the king’s army in the south. But, he deserted John when the French prince Louis (later Louis VIII) arrived to help the rebels. After John’s death, Salisbury served his successor Henry III and had a brilliant career. He died in 1226 (there was talk that he was poisoned), and was buried in the Salisbury Cathedral. When his tomb was opened in 1791, they found the well-preserved corpse of a rat inside his skull. The rat carried traces of arsenic!

The rat is now on display in a case at the Salisbury and South Wiltshire Museum.

Pembroke and Salisbury represented the finest side of mediaeval English chivalry and nobility. But there were also evil counsellors, who appear in Scott’s novel, though we don’t know how many of them were for real. One was Maurice de Bracy, a Norman knight who appears in the novel as the one who seeks the heroine Lady Rowena’s hand. But Rowena pains and pangs for the gallant protagonist, the Saxon knight Ivanhoe. An impatient de Bracy kidnaps her and her party on their way home from the tournament of Ashby. But, later, de Bracy is moved by her tears.

The evil incarnate in the Scott novel is Reginald Front-de-Boeuf, the lord of Torquilstone garrison where de Bracy brings Rowena and her party as prisoners. Reginald also tortures the Jew moneylender Isaac for 1,000 silver pieces. He is finally killed in the climactic battle of Torquilstone.

John’s chief adviser in the novel is Waldemar Fitzurse who sticks to the prince only for furthering his own prospects. At the end of the novel, when the gallant Richard returns to claim his throne back from John, Fitzurse leads an unsuccessful ambush against him, and loses. Richard banishes him from England forever.