They do it every time. Before the Chinese send their president or prime minister to visit a neighbouring country, they send a few troops across the border—just to test the neighbour’s military and political will.

Thus, ahead of Prime Minister Li Keqiang’s May 2013 visit, a few People’s Liberation Army (PLA) troops forayed into western Ladakh and stayed there for close to a month. They moved back only when India threatened to unleash the Tibetan protesters into Delhi streets to mar the premier’s visit.

Then, last September, ahead of President Xi Jinping’s flight to Ahmedabad and Delhi, the PLA sent a few troopers a few miles into what was held to be Indian territory in Chumar sector. They withdrew after Xi left India.

Such needling on the border is now taken more or less as part of China’s test-the-will diplomacy, but there was an added dimension to the needling on the eve of Xi’s visit. Apart from the border incursion in Chumar, the Chinese also tried to test India’s will and might, for the first time, in the waters. The PLA Navy sent two conventional submarines into the Indian Ocean and got the friendly government in Sri Lanka to allow them to dock at Hambantota, a port that the Chinese had built ostensibly for civil shipping in Sri Lanka.

It was no sneak arrival. On the contrary, the Indian Navy had come to know of the submarines’ arrival well ahead. Diesel-powered submarines have to surface almost every 24 hours during their underwater journey, to draw oxygen for recharging their batteries. “If they wanted the submarine mission to be a secret one, the Chinese would have sent nuclear submarines, which do not have to surface for weeks together,” pointed out an officer in India’s naval operations room. The Lankans, too, did not hide the fact that two Chinese subs had docked at their port. Clearly, the intent was to needle India.

India believes, and most of the world powers agree, that the Indian Ocean is India’s strategic backyard. With a powerful navy, India believes it can command the sea routes between the east and the west, through which a third of the world’s trade travels. “It is a role that we are expected to play,” said a naval officer. “The Indian Ocean has several choke points, which can be controlled by the Indian Navy. The world powers expect us to play that role. That is why virtually every navy in the Indian Ocean rim has been exercising with us.”

But, China does not agree. “The Indian Ocean Region (IOR) cannot be referred to as India’s backyard,” said Senior Captain Zhao Yi, a PLA Navy strategist and associate professor at the National Defence University, Beijing. “The word backyard is not very appropriate to use for an open sea. If the Indian Ocean was India’s backyard, then how are the navies of the US, Australia, Russia and other countries operating there? Possibility [of clashes] cannot be eliminated if you continue to consider this area your backyard.”

This is the first time that the Chinese have raised objections over the Indian role in the IOR, which the Indian Navy has been referring to as its area of responsibility for the past many decades.

And, the Chinese have been acting up on their belief. In November, the PLA Navy sent another submarine, this time a nuclear-powered one, which remained under water throughout its journey from its home port in the east. The Lankans allowed it to dock again at Hambantota.

Alarm bells rang in the Indian naval headquarters. The despatch of the nuclear-powered attack submarine (SSN) deep into the Indian waters, without having to dock in any neighbourhood port, was meant to be a show of muscle. “The next would be SSBNs,” said an Indian naval officer, referring to nuclear-powered submarines armed with nuclear-tipped ballistic missiles.

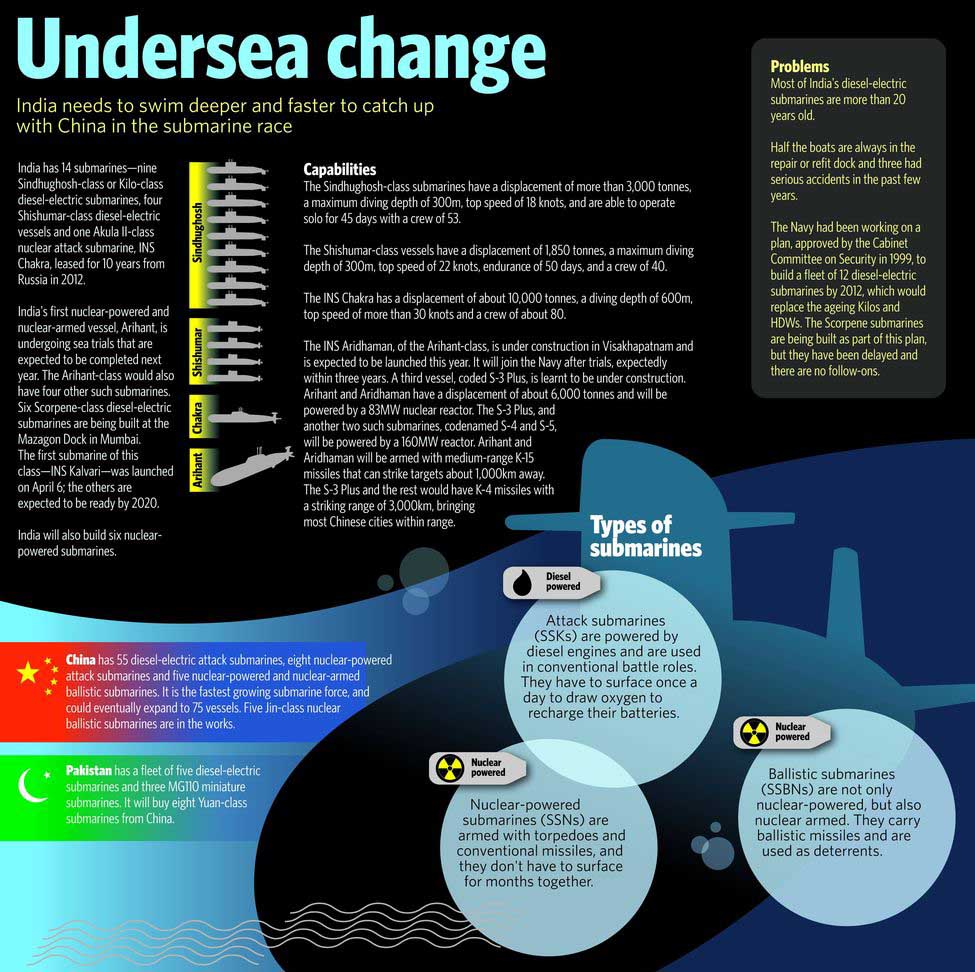

Submarines are of three kinds—SSKs, SSNs and SSBNs. SSKs, otherwise called attack submarines or conventional submarines, are powered by diesel engines and are used in the conventional battle roles. They have to surface almost once a day to draw oxygen for recharging their batteries, and that is when they get spotted by enemy ships, helicopters, reconnaissance planes or satellites.

SSNs are nuclear-powered submarines, but are armed with only torpedoes and conventional missiles, just like SSKs. Their advantage over SSKs is that they do not have to surface for weeks and months together, and thus can remain hidden from enemy eyes.

SSBNs or ballistic submarines are nuclear-powered and nuclear armed. They carry submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs) and are used as deterrence against a nuclear attack by the enemy. The philosophy is that the enemy would first take out India’s land-based missiles and nuclear bombers in a first attack. The submarine-stored missiles, which would be hidden under the sea, would then be used to strike back at the enemy. “It is a well-acknowledged fact that sea-based deterrence is the most survivable leg of the strategic triad,” Indian Navy chief Admiral Robin Dhowan told THE WEEK.

After the Chinese nuclear submarine visited Hambantota, the Research and Analysis Wing (R&AW), India’s spy agency, allegedly activated the plan to defeat Mahinda Rajapaksa’s China-friendly government in the Sri Lankan general election. It was alleged that the R&AW supplied opposition groups with secret communication equipment. India has since denied any interference in the election, but the result was to India’s liking. Rajapaksa suffered a surprise defeat. The new president Maithripala Sirisena’s visit to Delhi in February, his first foray abroad, was seen as a thanksgiving gesture. Sirisena is said to have promised Prime Minister Narendra Modi that no further Chinese subs would dock at Hambantota.

All the same, the Chinese threat has not exactly disappeared. On the contrary, the Chinese began showing that they can reach farther than Sri Lanka. In late May, a Yuan class 335 diesel submarine travelled farther north than Sri Lanka, crossed the Arabian Sea, “fairly close to Indian waters,” as a naval officer admitted, and docked at Karachi for nearly a week. “The idea was to show off the long endurance that even their diesel submarines have got,” the officer said.

The Chinese have been flexing the submarine muscle for some time now. “The Indo-Pacific region is important to us and it should be understandable for the Chinese Navy to go to the IOR,” asserted Senior Captain Zhao. In the last two years, Indian submarine-hunters have sighted Chinese submarines 68 times, passing close to Indian waters on the pretext of participating in anti-piracy patrols.

The Indian Navy is not convinced, saying you do not deploy submarines to chase pirates in the Gulf of Aden and nearby areas. Why not? ask the Chinese. “Why can’t submarines take part in anti-piracy operations?” asked Senior Captain Wei Xiandong, chief of staff of the Shanghai Naval Garrison, sitting in the briefing room of guided missile frigate Tong Ling in Shanghai.

In March 2014, a Chinese flotilla arrived off Andaman and Nicobar Islands, on the pretext of searching for the vanished Malaysian Airliner MH-370, but India shooed them away. “Such recce missions are undertaken basically to measure the depth and warmth of the waters,” pointed out an Indian submariner. “You need such data for finding out how your own submarine can operate in those conditions.” Indeed, the Indian Navy is concerned. “We are keeping a close watch on the movement of Chinese forces in and around our territorial waters,” Dhowan said.

India believes that China is building a series of strategic assets, called ‘string of pearls’, around the Indian peninsula. The ‘string of pearls’, India believes, would be a series of friendly ports and other maritime assets in countries around the Indian peninsula from where the PLA Navy would be allowed to operate. “There should be no concern about it, because, for China, defence policy is defensive in nature. We do not want to play a hegemonic role or to threaten other region or country,” Senior Captain Wei said.

But, Dhowan should be worried. For he knows that India is fast losing the naval edge that it had over Pakistan and China. Apart from owning a fleet of diesel-powered German HDW and Russian Kilo class submarines, Indian naval brass also used to boast that they had been operating mighty aircraft-carriers, the globally acknowledged symbols of maritime might, for the last 40 years, whereas China got its first carrier only a couple of years ago. And, Pakistan still has not seen a carrier.

But, both the adversaries have been building their maritime muscle in the last few years, while India’s has been depleting. Pakistan has got three brand new French-built Agosta submarines, and they are also learnt to have asked the Chinese for eight Yuan class submarines. China has a fleet of 55 conventional attack submarines, eight SSNs and five SSBNs. Another five Jin-class SSBNs are being built.

Against this, India has very little to show, or conceal. Against China’s 55 conventional attack submarines, India has a fleet of just nine Russian Kilo and four German HDW submarines, most of which are more than a quarter century old. The boats are so old that half of them are always in the repair or refit dock and three of them met with serious accidents in the last few years, leading even to the unceremonious exit of Navy chief D.K. Joshi.

Against China’s five SSBNs, India has none. India’s first SSBN, Arihant, is still undergoing sea trials, which are expected to be completed next year, after which the ship will join the Navy. Against China’s eight SSNs, India has one, INS Chakra, which has been leased from Russia for training and is not supposed to be deployed in an offensive role.

The Navy had been working on a plan, approved by the cabinet in 1999, to build a fleet of 12 conventional submarines by 2012, which would replace the ageing Kilos and HDWs. This would be followed by another 12 conventional submarines by 2030, and to have three Arihant-class SSBNs for strategic deterrence. The French Scorpenes are being built as part of this plan, but they been delayed and there are no follow-ons.

Meanwhile, the existing fleet is getting depleted. The Kilo class INS Sindhukirti, sent for repairs to Visakhapatnam in 2006, has just been upgraded and will rejoin the Navy next month. “At any given time, we have at least half the fleet in the repair or refit dock,” said a submariner. Two of the Kilo class submarines met with serious accidents in the last two years—the accident on the INS Sindhurakshak killed 18 and the one on the INS Sindhuratna killed two. Joshi quit soon after the Sindhuratna accident.

The crippling accidents, the long delay in refits and the quick pace at which adversaries are upgrading their fleet have now forced the Navy to ask for at least three nuclear-powered and armed SSBNs, six nuclear-powered but conventionally armed SSNs and 18 conventional diesel SSKs.

“The SSBNs will help India create a strong sea-based deterrent for second missile strike if China and Pakistan indulge in any nuclear misadventure,” explained Vice Admiral A.K. Singh, who was one of the first officers to serve on India’s first leased nuclear submarine, Chakra, in the 1990s. “On the other hand, the SSNs will help the Indian Navy to deploy for tactical missions in faraway locations such as the South China Sea.”

As it is, Arihant’s follow-on ship, INS Aridhaman, is under construction at the ship-building centre in Visakhapatnam and is expected to be launched this year. It will take another two or three years to join the navy, after sea trials and weapon trials. A third vessel, coded S-3 Plus and whose existence is still kept a secret, is learnt to be under construction.

Arihant and Aridhaman are learnt to be of 6,000 tonnes each and would be powered by a 83MW nuclear reactors; S-3 Plus will be powered by a 160MW reactor. So, will be two others, codenamed S-4 and S-5. Arihant and Aridhaman will be armed with medium-range K-15 missiles, which can strike targets about 1,000km away. S-3 Plus and the rest would have K-4 missiles with a striking range of 3,000km, thus bringing most Chinese cities within their range.

Indeed, the Chinese submarine-launched missiles have ranges up to 8,000km, but that does not worry India’s flag officers. “Those are their deterrence against the US, and we are not bothered,” said an officer. “Each navy develops its weapons with capabilities that meet its requirement. Since our submarines will be able to strike anywhere in China with missiles of 3,000km range, we are not bothered about comparisons.”

The worry is not about range of the weaponry or capability or endurance of the vessels. The worry is about the long gestation period that ship-building programmes involve. There is still no finality on how and where these boats will be built, and how long they will take.

With nearly half a dozen nuclear submarines being planned to be launched in the next 10-15 years, training the crew is a major concern. The Russian Chakra has been taken on lease essentially to train the crew in nuclear submarine operation, but now the Navy feels that it needs one more boat to train the crew. Prime Minister Narendra Modi has asked Russian President Vladimir Putin to lend one more ‘training’ nuclear sub, which is expected to arrive by 2018.

According to the naval brass, India would need a fleet of at least 11 nuclear submarines (both SSBNs and SSNs). “Submarines are primarily designed for sea denial missions,” Admiral Dhowan told THE WEEK. “They are also typically employed for a vast spectrum of other tasks ranging from defensive to offensive missions. In addition, strategic submarines provide a significant deterrence capability.”

WITH R. PRASANNAN/DELHI