A year ago, when newly anointed Prime Minister Narendra Modi articulated the great Indian dream of a hundred smart cities, a smart phone-enabled generation perked up. The vision that flashed before their eyes was straight out of android land—cities with electronically fitted homes, seamless public transport, Wi-Fi enabled public places... indeed, a land where lives ran with digital precision, aided with an app for everything.

Then they rubbed their eyes, and took in the reality around—inundated roads and traffic chaos, power cuts and water wars, unsafe women and red-taped governance. Just how would anyone smarten up all this, and by when?

In the year it has taken for the government to give a policy framework, and more importantly, an outlay of Rs98,000 crore to Modi's vision, India has understood that this Modivian transformation is not an overnight (or for than matter, even a one-elected term) process. Cities, after all, cannot be upgraded from kitkat to lollypop at the speed of a smart gadget. That does not, however, mean that the slow wheel of transformation is not going to turn. It already has.

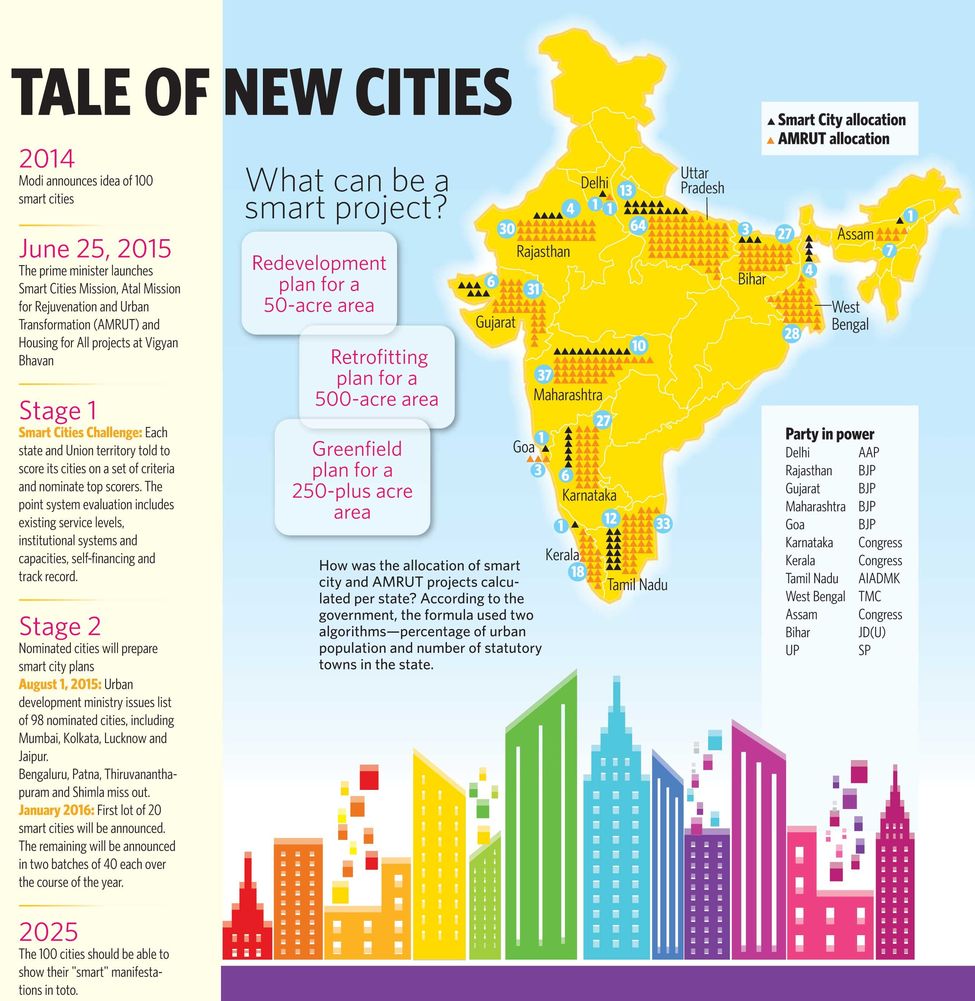

The Union government has allocated Rs48,000 crore for the smart cities project, and Rs50,000 crore for the Atal Mission for Urban Rejuvenation and Transformation (AMRUT), a sibling scheme with a slightly different focus.

But there was a catch. You had to earn your right to be smart. Cities had to vie with one another to get the Rs500 crore each over the next five years. The results of the first stage of the smart competition are out. And, the Union government has asked local municipal authorities to come up with plans, in consultation with residents and local groups, to smarten up their towns and cities.

Modi, however, has inserted words of caution: suggest doable things, offering smart solutions that could be game changers, rather than throw up mega wish lists.

While the Union government may have given the number of cities to be chosen from each state (depending on size and, perhaps, political affiliation), within each state, cities had to compete for the funds. Also, the state governments have to put in Rs1,000 crore per selected city over a five-year term towards the smart project.

So, cities such as Ajmer, which believed for nearly a year that it was a “chosen one”, ruefully realised that they would be chosen only if their proposal is smarter than, say, Jaipur or Bikaner (Rajasthan is allowed to develop four cities under smart cities project). Both Ajmer and Jaipur cleared the first hurdle, though Bikaner is out.

In the list of 98 cities selected at the end of the first stage of competition, some surprises have popped up. In Himachal Pradesh, Shimla lost out to relatively smaller Dharamsala; in Bihar, Bihar Sharif pushed capital Patna aside. State capitals such as Gangtok, Bengaluru and Thiruvananthapuram also didn’t clear the first smart level. Though there was a buzz about Kochi, not a single city from Kerala made the cut.

Now, these cities have to submit Smart City Plans, which will be whetted by the urban development ministry to select the first 20 “chosen” cities.

This means that a smart proposal for, say, Guwahati in Assam could be different from what Tirupati in Andhra Pradesh may come up with. If smartening up traffic movement is the proposal of one city, another might want to focus on greening the power grid, while another may have a solution to address perennial flooding. Thus, no two smart cities will be the same.

What then is smart? As Union Urban Development Minister Venkaiah Naidu says a smart city is one which enables decent living, a clean and sustainable environment and adopts smart (read technological) solutions to meet these needs.

Research: Rekha Dixit, Graphics: N.V. Jose

Research: Rekha Dixit, Graphics: N.V. Jose

“You don't have to be ultra-modern to be 'smart'," says Shailesh Pathak, executive director, Bharatiya Urban, a realty company that is developing a gated smart enclave on the fringes of Bengaluru. “Cities of the Harappan civilisation were smart even by today's definition, with brick-lined drains and right-angled roads. The only difference is that today there is information technology.”

The rich in India already lead smart lives, says Pratap Padode, head of the India chapter of Smart Cities Council, a global consortium of solution providers, practitioners and academics who aim to promote smart cities. “The clincher will be for each city to come up with that one single solution that makes a drastic change in the overall life of its people,” he says.

Indeed, even before Modi articulated his smart cities vision, urban rejuvenation was ongoing, notes Padode. “Delhi Metro was a game changer. The Bus Rapid Transport routes are success stories in Ahmedabad and Indore. Agartala recently invested Rs20 crore in smart city lighting, sprucing up 33,000 street lamps, having calculated that the savings in the power bill will pay back the loan eventually,” he explains, adding that Modi's scheme has only given direction and funds to the process of urban rejuvenation.

But, will retrofitting and redeveloping 100 existing brownfield cities by 2022 address India's burgeoning demand for decent urban living? Every town planner, demographer and economist swears by the Mackenzie Global Institute Study of 2010, which predicts that 70 per cent of India's Gross Domestic Product (GDP) will come from urban areas by 2030.

The India-lives-in-its-villages idyll made the first noticeable shift in Census 2011, which recorded that 31 per cent of Indian population lived in urban areas. “By 2041, it will be 50 per cent,” says Pathak.

Says Talleen Kumar, CEO, Delhi Mumbai Industrial Corridor Development Corporation, “India is urbanising at such a pace that every minute, 30 people migrate from a village to a city. If we do not create urban areas for these people to migrate to, existing cities will become slums.”

Kumar is heading, perhaps, the biggest urbanisation project in India, which aims to develop eight new mega-cities along the Dedicated Freight Route, an ambitious plan of the Indian Railways to create a rapid transit railroad from Dadri on the outskirts of New Delhi to the Jawaharlal Nehru Port Trust near Mumbai.

The biggest of these cities will be Dholera, about 100km from Ahmedabad, and sprawled over 920sq km. The first phase of the project is expected to be completed by 2019. By 2040, Dholera is projected to house 20 lakh people. As all the urban nodes on the corridor are being planned around industries, Kumar says the project will be a solution to three challenges modern India faces—rapid urbanisation, planned infrastructure and increased manufacturing.

“Our job is to plan and lay the basic facilities that will attract the private sector to invest in manufacturing and building residences,” says Kumar. These cities of the future, he adds, will pierce the skyline, and incorporate the latest technology in sewage treatment, power distribution, flood water management and sustainability.

“Since Indian cities are lagging so far behind the demands of the present, it is an even greater challenge for us to predict the demands of a distant future and cater to them,” he notes.

These mega-cities, however, are part of a distant dream; many are still in the land acquisition phase. But that has not stopped the Union government from announcing four similar freight/industrial corridors: Bengaluru-Mumbai, Chennai-Bengaluru, Visakhapatnam-Chennai and Amritsar-Kolkata.

Realists argue that brownfield rejuvenation will be the driver of bettering urban life for the next decade at least. “By 2020, Dholera won’t have a population of even a lakh,” says Pathak. “Migrants will continue to flock to existing urban areas, so smartening them up is an urgent need.”

Recent urban growth in India, however, has been erratic, pro-rich and so random that many are classic examples of exactly how not to urbanise. Millennium city Gurgaon is a case in point. The mofussil township of one lakh people (1981) enumerated over 15 lakh in the 2011 census.

The city—named after Guru Dronacharya of the Mahabharat, who was gifted the village for training the Kuru princes, thus, guru-gaon or the teacher’s village—grew, acquiring arable tracts from nearby villages, and attracted commerce and well-heeled residents to its plush glass-and-chrome offices and gated communities, complete with swimming pools that sucked the water table bone dry.

The sociological chaos that Gurgaon’s growth created is regularly chronicled through ghastly stories of crime, especially against women. The nearby villagers are, after all, inhabited by men who became rich by selling land, but have no occupation or employable skills to get absorbed in Gurgaon’s economic boom.

Worse, the millennium city stops in its tracks the moment it receives a liberal sprinkling of rain, as it is seen now with the ongoing monsoon spell. “They are now planning to retrofit Gurgaon with storm water drains and flood control measures,” says Kumar. “It should have been part of the urban planning before the city grew.”

Indeed, private sector participation without accompanying civic infrastructure is now telling on most urban areas that have had a visual facelift.

Mumbai’s central area of Lalbaug-Parel, which metamorphosed from mill-worker land to neo-rich land over the past decade, is another example. While skyscrapers have added to the population load, civic amenities have not been upscaled, resulting in a mess of potholed roads, uncleared garbage and flooding drains outside every gated complex.

The discordance between the government and the private sector may be to blame in most cases, but complete private sector initiatives have not had success stories either.

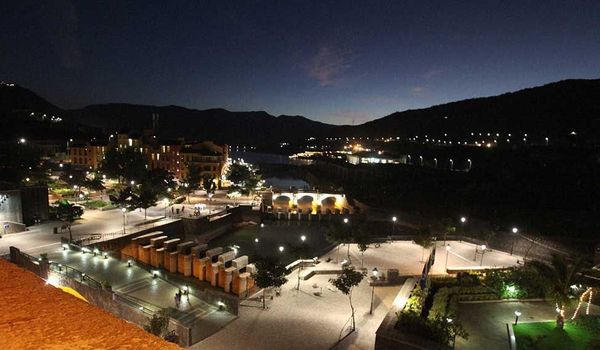

Lavasa was sold as a dreamland in the mid-2000s. A picturesque lakeside town in the Western Ghats near Pune, where you could walk to work from your ultramodern home to an office of similar amenities. Only, it turned out that there was no work to do in the office.

Poor planning: Lavasa, India's first planned hill city, failed to strike gold | PTI

Poor planning: Lavasa, India's first planned hill city, failed to strike gold | PTI

“A town has to have an economic driver, only then will it attract people. Lavasa had none,” says Padode. “First it was sold as a tourist destination, but there was no tourism. Then they tried selling it as an education destination. Forget the environmental issues it ran into, it was unplanned in terms of economic propositions.”

Pathak highlights another example. “The Special Area Development Authority project in Gwalior West, which aimed to be a counter magnet to Delhi, is another flop, as it has no employment to lure residents,” he says (read 'Smarting city', THE WEEK, May 27, 2015) .

What, then, is the direction that India’s urbanscape will take? While the mix of greenfield projects, and retrofitting, redeveloping and extending existing cities will ensure that urbanisation remains a dynamic process, it will be the vision of the developers that would ensure a success story from a Muhammad bin Tughlaq-type failure.

Experts stress the importance of predicting a future need, not formulating a stop-gap measure to sort out a crisis. For instance, will creating more flyovers be a more sustainable solution than ensuring fewer cars through a robust public transport system?

Also, there needs to be a dynamic leadership at the city level, like a Rudy Guiliani (former New York mayor), the face of New York after the 9/11 attacks, or Ken Livingstone, who introduced the controversial but daring congestion charges to dissuade car traffic in central London.

“Bengaluru is a city of activists, yet their combined activism has not smartened up the city in any way,” says Pathak, who believes mega-cities should be free of state control and allowed to chart their growth courses. “Unfortunately, our laws do not permit that any mayor ever gets a second term, so the idea of a city leader is aborted even before inception.”

Smartening is a continuous process, says Padode, citing the classic example of how Spain's Barcelona, a compact city where most destinations are accessible by foot, cycle or public transport, is smarter than Altanta in the US, which though has the same population, has such a sprawl that its residents are fuel-guzzlers. “Barcelona is smart by today’s standards, but it may not be in future, if it does not change according to changing needs,’’ he says.

Who knows this better than Jayesh Ranjan, tasked with the challenge of retrofitting Cyberabad, which, though the most modern enclave in Hyderabad, is already falling short of global standards. From greening buildings to making them disabled-friendly to tackling the emerging problem of e-waste, he had his job cut out for him. “Just when you think you have achieved your goal, the goal post shifts,’’ he says.

Ways to get phat

Greenfield city

One that starts from scratch. This kind of a project could take decades, as the processes―right from land acquisition―are slow.

Advantage:

* The latest technology can be used right from the foundation

Disadvantages:

* Environmental and land rights issues

* Cost-intensive

* Requires a good visionary, or else there is risk of the project flopping

Examples: The nodes on the Delhi-Mumbai Industrial Corridor; Amaravati, the new capital of Andhra Pradesh; and Lavasa in Maharashtra. Also, many extensions of existing cities are greenfield projects.

Brownfield city

This is the modernising or “smartening up” of an existing city.

There are two types:Redevelopment projects Pulling down existing infrastructure of a city and rebuilding the area.

Advantages:

* Land acquisition not required

* Some existing infrastructure such as arterial roads can be left intact

* Enclave gets modernised at a reasonably low cost and less environmental damage

Disadvantages:

* Getting sanctions from stakeholders of the area can be a challenge

* There should be consonant development of the neighbourhood of the enclave

Example: The ongoing East Kidwai Nagar project in Delhi. It is primarily a low-rise government staff housing enclave of early post-independent India, and the redevelopment of 86 acres here will be a combination of residential and commercial complexes housing government offices. The 15-storeyed buildings will be built using latest technology.

Retrofitting projects

The smartening up is done around existing infrastructure. It is technology-driven, finding smart solutions to improve the quality of urbanisation. Retrofitting projects include making Wi-Fi zones, creating green technology for waste disposal and reducing power consumption. The bulk of smart cities in the years to come will be created through retrofitting.

Advantages:

* No major reconstruction

* No land acquisition

* One smart solution can be taken up at a time

Disadvantages:

* At times, working around existing infrastructure is more challenging than building from scratch.

* Requires permission of various stakeholders.

Example: Ongoing smartening up of Cyberabad