Nations that do not remember their immediate past are in danger of repeating the same tragedy. This thought comes to me when someone under 35 years of age or even 55 draws a blank on being asked about the significance of June 25, 1975. Even newspapers never front-page it―some do not even carry the information; a few may just mention it somewhere in the corner of inside pages. Many opposition parties that were the victims of the Emergency choose to keep it low key, though the People's Union for Civil Liberties and such other organisations as usual hold protest meetings.

And yet, it was a day when India lost its democracy, and the US president sarcastically boasted that the US was now the largest democracy. Because of the sacrifices made by Indians under the inspiring leadership of Jayaprakash Narayan, the boast ceased to be true, but only after 21 months.

There was spirited resistance to the Emergency. Thousands went to jail, and many human rights activists worked underground. But, there is a limit to which unarmed people can fight an intolerant and a near fascist state that India had become those days.

In times of crisis like during the Emergency, the judiciary is expected to act as a bulwark against the excesses by the executive. But a fatal blow to freedom was struck by the Supreme Court judgment in the ADM Jabalpur case in 1976, holding that the right to life does not survive during the Emergency. The ruling overruled the view of nine High Courts that the legality of detaining order passed by the government could still be set aside for illegality. In fact, in some cases, the High Courts had ordered the release of detainees. But, the Supreme Court, by a majority of four judges against one honourable exception of Justice H.R. Khanna, laid down thus:

“In view of the Presidential Order dated June 27, 1975, no person has any locus standi to move any writ petition under Article 226 before a High Court for habeas corpus or any other writ or order or direction to challenge the legality of an order of detention on the ground that the order is not under or in compliance with the Act or is illegal or is vitiated by mala fides, factual or legal, or is based on extraneous considerations.”

The Supreme Court accepted the attorney general's argument that if a policeman, under orders of his superior, was to shoot a person or even arrest a Supreme Court judge, it would be legal and no relief available. I am shocked how the majority decision could rely on the Liversidge vs Anderson judgment, given during wartime in 1942 by the House of Lords (United Kingdom), when English courts subsequently felt so ashamed of that decision that a conscious effort was made to throw it in a dung heap.

Some commentators have ironically described the majority in Liversidge case as the court’s contribution to England's war effort. Similarly, many in India are inclined to describe the majority in the Jabalpur case as the Supreme Court's contribution to the continuance of the Emergency. Had it taken the same view as the High Courts, the Emergency would have collapsed because no court could have upheld the detention of stalwarts like Jayaprakash Narayan, Morarji Desai, Raj Narain, George Fernandes, Madhu Limaye and brave journalist Kuldip Nayar on the ground that they were a danger to the nation's security. The inevitable result would have been the immediate release of these leaders, leading to an overwhelming opposition movement which would have swept away the Indira Gandhi government by mid-1976. Alas, how sometimes fate of nations can be influenced by the pusillanimity of a few individuals―in this case embarrassingly by the highest judiciary, which it can never live down.

Soon after the change of government, Justices Y.V. Chandrachud and P.N. Bhagwati expressed regret and conceded that they should have joined Khanna, which would have been the majority. But this crying over their earlier view is like crying after having deliberately spilt the milk. So much distrust in judiciary had been generated that Parliament took precaution in passing the 44th amendment to the Constitution (1978), which has taken away the power of the president to suspend Article 21. But, we must continue to remember that “eternal vigilance is the price the nation must pay for safeguarding the liberties of individuals”. And the press should keep reminding the public of this frequently.

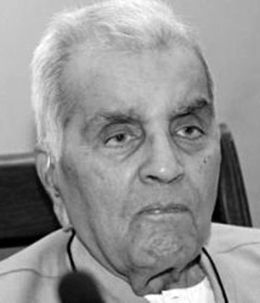

Sachar is a former chief justice of the Delhi High Court.