What would you call two bright, talented and well-qualified city pigeons who left their cushy jobs, moved to a village 180km from Pune, and started living among the villagers? Loony? Perhaps. Brave? Likely. Determined? Most certainly. In 1987, Dr Ramesh Awasthi and Dr Manisha Gupte moved to Malshiras in Pune district, spent five years there, and started Mahila Sarvangeen Utkarsh Mandal (MASUM).

The organisation works with marginalised women in about 20 villages in Pune and Ahmednagar districts of Maharashtra and has, through community participation, made them capable of standing up for their own rights and fighting for the rights of others. “Every programme is ‘rights-based’,” says Gupte, a microbiologist and sociologist. “We are not there to do charity. People are not beneficiaries, but active participants in the process of social change.”

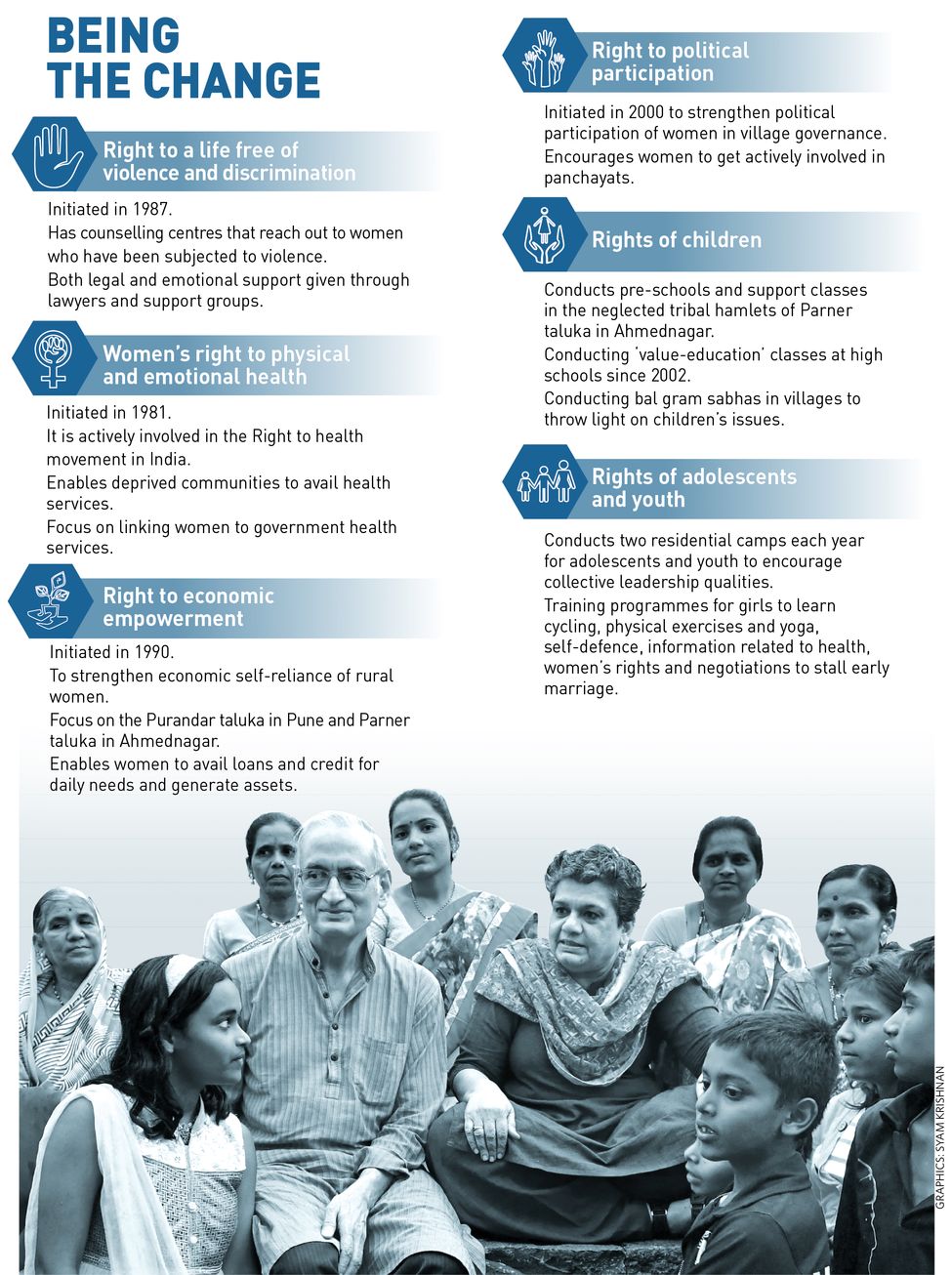

MASUM currently has six programmes, which relate to women’s right to emotional and physical health, to a life free of violence and discrimination, to political participation, to economic empowerment, and two programmes for youth and child rights.

“We are only the agents who are there to bring about a consciousness that life can be much better if there is an equal, democratic society with no violence, disparities or discrimination,” says Gupte, 61.

The couple were active in the Jayaprakash Narayan [JP] movement of the 1970s. Besides attending meetings and marches during the Emergency, Awasthi distributed Satya Samachar, an underground newspaper, and they both worked with the influential students organisation Chhatra Yuva Sangharsh Vahini. He was the son of a doctor, from a Punjabi family that had moved from Pakistan to Uttar Pradesh during partition. She was part of the third generation of social activists in her Maharashtrian family. Though they were from vastly different backgrounds, the ideology of total social transformation brought them close. They met as the Emergency was being lifted, remained friends for a bit, and finally tied the knot in 1982.

All those years, they had carried with them the seeds of transformation; all they wanted was fertile ground. They found a mentor in Dr N.H. Antia, a renowned plastic surgeon known for his work with leprosy patients in Pune. Gupte and Awasthi were working at Antia’s Foundation for Research in Community Health when they told him that they wanted to move to a village. He asked them to write a project proposal, which got them a grant for a rural health education project.

The reasons for moving to a village were plenty. Awasthi felt that if democracy had a life, it would be at the grassroots level. “Besides, JP used to say… ‘to see the real India, go to the villages. If you want to change the country, go live with people, speak less, see more, feel more about what is happening there, don’t go with answers. Learn the heartbeat of the country and the answers will come from the people, not from you. Walk hand in hand with people, don’t desert them.’ So, we felt we should go stay in a village,” he says.

Awasthi, an alumnus of IIT Delhi with a master’s degree in economics, was interested in rural development. So, they drew up a plan and went around looking for places that needed health education. After visiting many talukas in Pune district, they zeroed in on Malshiras. They decided to work with three primary health centres, which covered about one lakh people.

Lasting bond: Gupte with friends at Malshiras village.

Lasting bond: Gupte with friends at Malshiras village.

“Before we went there [Malshiras], we had got a grant to start a project for women’s employment from the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation [NORAD],” says Awasthi, 67. “And, talking to women [in the village], we learned that they had already started demanding their rights, and said they should have a place of their own. And so, under MASUM, we started a handloom project there, by installing eight looms, where weaving was done by women from Malshiras and 18 neighbouring villages.”

Thus began the MASUM journey. And, though it was hard work, the couple’s time in Malshiras was certainly not dull. “What happened 9 to 5 was quite different from what happened 5 to 9,” says Gupte. They would be surrounded by dalits, minorities and artisans, and the highlight of each evening would be the question: “ST aali ka? (Has the state transport bus arrived?).” Its arrival would signal the official onset of night.

During their stay, Awasthi wore several hats, from being the snake and scorpion catcher (he released them in faraway fields after making logbook entries) to being the local handyman, repairing transistors, watches and televisions. As payment for his efforts, the villagers taught him Marathi. Now, he is as fluent as a native speaker.

After five years, Gupte and Awasthi moved back to Pune, but have continued their association with MASUM. They visit the villages at least once a week.

The organisation has, over the years, built offices in Hadapsar and Saswad in Pune, and Parner in Ahmednagar. They have counselling centres in Saswad and Yawat, and health and paralegal centres in 15 villages.

Right to life without violence

Health and wealth: A training session at a MASUM health centre.

Health and wealth: A training session at a MASUM health centre.

Though they completed their initial health project while in Malshiras, Gupte and Awasthi were not satisfied. They wanted to socially transform the villages. The first major programme they started, in 1987, was the one related to women’s right to a life free of violence and discrimination. They formed counselling centres, called Samvad, to reach out to survivors of abuse. These centres also work closely with the free legal aid centre of the Pune district court, crisis shelters and other women’s organisations in the area.

Moreover, female support groups, locally formed, intervened at the household level to stop violence. “I was trained at MASUM for helping women who have faced domestic violence,” says Sheetal Chavan, MASUM staffer. “MASUM prepared support groups in different villages and now I help women through a support group.”

Slowly, people came to accept the MASUM women. “Men also understand that laws now support women and that they will not put up with violence of any kind,” says Malan Zhagade, a MASUM counsellor.

MASUM also brought in social workers and senior lawyers for their expertise and trained local women in how to handle survivors of abuse. People were trained to be paralegals, called Saathis, for two years, and then offered legal support to women at dedicated centres in 15 villages. They were trained not only to understand patriarchy and gender issues, but also to identify domestic violence. “From taking a woman’s application to sitting down and telling her that her husband cannot trouble her or her children, [especially] if he doesn’t help her financially, all these things are looked into here,” says Sunanda Khedekar, counsellor and team leader at the Samwad centre in Saswad. “Every Wednesday and Saturday, lawyers study the papers, after which the cases go to court. All the paperwork is done here,” says Zhagade.

Take, for instance, the case of Surekha. Since her wedding, her husband, Ravindra Tatyaba Shinde, always found fault with her cooking and housekeeping. His brother and sister-in-law would join in. “My father-in-law and brother-in-law married twice, so my sister-in-law would keep prodding my husband with questions like: ‘When are you going to leave her and remarry?’ My husband would get upset with all this talk and would beat me up. They used to abuse me a lot, mentally and physically,” says Surekha. “After I delivered a baby girl, nobody from my husband’s side came to take me and my daughter back. Instead, he asked for a divorce, which I said I wouldn’t give. That is when I registered a complaint and the matter was taken up in the Saswad court. Of course, my husband wasn’t happy that the matter went to court. He wanted a mutual divorce, but he had hit me a lot, he had hurt my head, my back and, when I was pregnant, he had even given me pills to abort the child. I said I wouldn’t do it, so he kicked me several times in my stomach. Our daughter is eleven but he hasn’t seen her yet. In fact, after four years, without divorcing me, he remarried, on the sly. He said to me ‘If you had not complained, we would have come to take you back. As you did, we won’t now’.”

Surekha’s uncle told her about MASUM and she contacted the organisation in 2009. “They gave me a lawyer, who would send notices to my husband,” says Surekha. “He would also help me with responses when my husband refused to accept the legal notices. Kavita Jagtap and Mangal Kunjir at MASUM helped me a lot.”

Right to health

Awasthi and Gupte started a savings and credit programme at Malshiras village.

Awasthi and Gupte started a savings and credit programme at Malshiras village.

In 1991, MASUM started its health programme, with the focus on bettering access to health care among the most deprived sections of the community. They trained a few people from each village, for two years, to be health workers, or Sadaphulis. As early diagnosis improves the chances of treatment, these workers asked women to understand their bodies and self-examine themselves. They conducted regular examinations at the village level, which have helped detect, among others, cervical cancer, reproductive tract infections and gynaecological problems. “From taking women to hospital to getting them operated, MASUM helped us a lot, especially when it came to uterine surgeries,” says Chhaya Ved Pathak of Mavdi village. “Even cancer patients are often tested by MASUM’s trained workers in the village itself. MASUM helped us at every step of the way, from organising health camps to diagnosis to surgery to even recuperation.”

MASUM also set up a generic drug store, which became quite successful, but it was shut down after the organisation’s work expanded. Distribution of drugs still continues, but it is now done through health workers, says Awasthi.

Right to economic empowerment

In 1990, Antia visited Bangladesh, where he met Muhammad Yunus, the social entrepreneur of Grameen Bank fame. Impressed, he brought back literature regarding the microfinance organisation and gave it to Awasthi. Soon, a savings and credit programme, which worked through self-help groups, was started in Malshiras. Women would save small amounts every month and take low-interest loans without any collateral.

“We started running that model in 1990 and started giving loans. We changed Yunus’s method a bit and, with Gandhian and democratic principles, we decentralised it,” says Awasthi. “With Balutedar [servant caste] women conducting these meetings, it changed the power equation. A Maratha woman had to give a loan application to a Balutedar woman. It was done in subtle ways, under MASUM, to change things.”

As the programme progressed, a close connection was seen between malnourishment, illness and indebtedness. Because of malnourishment, there was illness, which led villagers to doctors, who often exploited them. To pay doctors, the villagers took loans, became indebted and did not have enough money to provide proper nutrition to their family. Thus went the cycle. MASUM, however, changed that. “Before MASUM, we would borrow money from moneylenders; those in dire need would borrow it on higher interest rates and it was very difficult to pay back the sum,” says Chhaya Ved Pathak, who bought a sewing machine with a MASUM loan. “We would have to pay Rs 10 interest on every Rs 100 borrowed. But, at MASUM, it was Rs 1 and we were given up to three months to repay it. From the fourth month, we could pay it by instalments, so MASUM really helped us a lot.”

Right to political participation

Kavita Jagtap

Kavita Jagtap

During their programmes, Gupte and Awasthi found that the rural women were reluctant to enter the public space to voice their concerns. Seeing this, the couple began with political participation in the male-dominated gram sabhas. They created a mahila gram sabha, which was held a day before the regular gram sabha and, soon, the women felt empowered enough to participate in the latter. Once the women were made to realise that the village council was their space, too, they ended up going to the sarpanch, getting the key, and holding meetings on the panchayat office premises. “MASUM made women aware about their options and then we started going to the gram sabha. Before that, we didn’t know any better and women’s lives were restricted to chul ani mul (stove and child),” says Maya Shinde, a villager. “We not only got cupboards and iron pans, but also got electricity. Now, men and women are equal and most homes in the village have nameplates with both names on them.”

Rights of children and youth

As catching them young was a priority, MASUM also started two programmes for children and youth—Ranpakhre (children of the jungle) and Bharari (taking flight). Every Saturday and Sunday, nearly 2,000 children meet in each village for games such as carrom, skipping and cycling. They also have a Pustak Samiti, or book council, as well as a library. “Most of the children here love reading and it is not limited to just Marathi books; they also read English books,” says librarian Nikita Bhimrao Satav. “Children of Mavdi village read books on Shivaji Maharaj and Lokmanya Tilak, and even on great scientists and the environment. It is my job to lend them books and make entries in my records whenever they are returned.”

In the course of the programme, children were also made equals in the transformation. When it was found that there was a deficiency of vitamin A, which led to night blindness, the children were taught how to identify it. “When a child, late in the evening, holds your hand or needs your help to go back to his or her house, that means there is night blindness,” says Awasthi. “This resulted in students themselves identifying others with night blindness and, on one occasion, 40 of them turned up at a primary health centre and asked for vitamin A.”

A bal panchayat of 10 children—five boys and five girls—was formed in every village. In these, children create their own manifesto and are elected to office. There are five committees, with two children each, for education, recreation, culture, books and communication. They are taught about child rights and are told to look out for children in need, be it a fellow student who drops out of school or one who is forced to get married. The children also hold their own gram sabhas, where a number of issues are raised, including the need for clean drinking water, violence in school, dalit children being made to sweep floors and inappropriate advances by male teachers. The children, defending their right to independence, say, “You say that men cannot raise women’s issues, so how can our mothers and fathers raise our issues?”

Youth, too, form an integral part of MASUM’s efforts and, every year, two residential camps of three days each, consisting of 100 boys and girls, are conducted to encourage youth advocacy and to create awareness.

Jagtap’s journey

The biggest change MASUM can claim to have brought is in the mindset of the villagers. When Kavita Jagtap, a semi-educated dalit woman from a poor family, became part of MASUM, she was a nobody. Now, sometimes, even the sarpanch rings her up late at night, asking her to tell the police to take up the case of an abused woman. She calls the officer and, voila, the police register the case. “Now, if I make a call, the police also take proper action, especially when the women go on their own and say Jagtap madam has sent me,” says Jagtap. “Then the police sit up and take notice. That much we have achieved over the years.” Sometimes, even the judge calls her inside his chamber to discuss certain cases.

But, how did this happen? “There was a case of sexual harassment of a village girl,” says Awasthi. “The village leadership and other powerful people came into the MASUM office and demanded that we withdraw the case. Jagtap, though alone at the office, didn’t yield, and despite being threatened, stood her ground with the Maratha leadership of the village. It was simply remarkable.” And, thus, a legend was born.

Jagtap, however, is just one of many women who have found their feet, and voice, over the years. “MASUM has made us independent. A lot of other organisations come and distribute free goodies and go away, but MASUM has made us independent in our minds and has encouraged us, both women and children, to think freely. That is what distinguishes MASUM from others,” says Sheetal Chavan.

Taking their message of self-help forward, Gupte and Awasthi withdrew from their leadership position in 2010, paving the way for a second generation of leaders in MASUM. “The culture we want in the country—transparency and accountability—has to be there in the public distribution of every institution,” says Awasthi.

So, they selected six team leaders for their six programmes. These leaders assemble in December, and prepare their monthly activity plans, annual plans as well as annual budgets. While each staff member has multiple responsibilities, the main aspects remain health, paralegal and microfinance, as these require specialised training. Currently, MASUM has 43 staff members, urban and rural, most of whom come from the minority and marginalised communities.

MASUM has also recently started a Lokshahi Utsav (democracy festival) in Pune. If democracy has to be saved, let us celebrate what we have, says Awasthi. “After all, a weak democracy can only be replaced by a strong one.”

COURAGE AND CONVICTION

Along with knowledge, skills and a platform, MASUM provides courage, too. Vatsala Deokar, a MASUM field worker, was the only witness in a case where a woman from her village, Sharda Ashok Deokar, was burnt to death—she died in her arms, in an ambulance. Sharda, in her dying declaration, had told Vatsala that her husband, Ashok Maruti Deokar, had doused her with kerosene and set her ablaze. The husband’s relatives went to Vatsala’s house with Rs 5 lakh, telling her to take the money, use some of it, and give the rest of it to MASUM. Vatsala told them that neither she nor her organisation took “tainted money”, before sending them packing. “You may not want to continue the case,” she told them, “but Sharda’s voice rings in my ears day and night as she kept telling me ‘Me ata janar pan tyala sutti naka deu (I am going to die but don’t let him escape).’ I cannot betray that dead woman.”

Fearing that she would be attacked on her way to court or that her case file would be snatched away, Vatsala sent her daughter, Sangeeta, with the file, to the MASUM office a day before the hearing. The following morning, Vatsala collected the file from the office and reached the court. Her lawyer insisted that the evidence would not hold ground and that the judge would laugh it off. Vatsala, however, persisted, and the judge accepted the evidence, sentencing Ashok to life imprisonment. “That is the kind of moral and ethical character you want to build among your staff,” says Gupte.