A white Scorpio with net curtains drives slowly through crowds. It is afternoon, and Jodhpur's sand-coloured court complex is crowded. To get to the last courtroom, one needs to head past the sprawl of lawyers in their shiny black suits, their typewriters clicking away. In the courtroom, proceedings against Asaram Bapu, Jodhpur’s most high profile prisoner, have just resumed.

The last witness to depose―Chanchal Mishra, former Jodhpur assistant commissioner of police―walks out. She has been on the stand for a month. The investigating officer and her team were responsible for putting away the 74-year-old self-styled god-man, for the alleged sexual assault of a minor.

Since the trial began, nine witnesses have been attacked. Three have been silenced. The rest live with the certainty that they might be next. LIC agent Kirpal Singh, a prime witness, was shot dead in Shahjahanpur, Uttar Pradesh. Akhil Gupta, Asaram's cook and personal assistant, was a key witness. He was shot dead in Muzaffarnagar, UP, in January. Amrut Prajapati, another witness, was shot dead last year.

Rahul Sachan was stabbed outside the Jodhpur court, after he gave his testimony. So, was Mahendra Chawla. Both lived to tell the tale. Arvind Bajpai, a school principal, who testified against Asaram received a parcel at home―live ammunition wrapped in a newspaper. Dinesh Bhavachandani, who has survived several attacks, had acid thrown at him in the latest one. The victim has rarely stepped out of her well-guarded house in the past two years. Once, to have her testimony recorded and then for her class 12 exams.

The deputy commissioner's office received threat letters by fax. The judge received threatening postcards. There is also the subtle warning. Last year, Asaram's followers were found distributing pamphlets outside Mishra's son's school.

Witnesses in India, especially if it is a criminal case, are certain that there will be consequences. “The best way is to shoot them,” says P.C. Solanki bitterly. He represents the girl whom Asaram allegedly raped. A bullet is cheap, effective and guarantees silence forever. There are other ways, too.

No word, no bond: Zaheera Shaikh, prime witness in the Best Bakery case, was sentenced to three months rigorous imprisonment for giving false evidence | PTI

No word, no bond: Zaheera Shaikh, prime witness in the Best Bakery case, was sentenced to three months rigorous imprisonment for giving false evidence | PTI

“It is neither safe, nor viable to be a witness,” says Rebecca John, senior criminal lawyer. “Witnesses are intimidated, bought off or bumped off. In the Jessica Lal case, Manu Sharma ‘told’ the witnesses to commit perjury. The cases drag for so long that unless you are determined, you will naturally lose interest in the case.” John was referring to the case of April 1999, in which Manu Sharma had shot Jessica Lal, a model, in the head at the bar of New Delhi's Tamarind Court restaurant.

The Supreme Court has voiced the same concern, albeit a little more eloquently. In National Human Rights Commission vs State of Gujarat 2003, a Supreme Court bench said the time was ripe “to act on the numerous experiences faced by the courts on frequent turning of witnesses as hostile, either due to threats, coercion, lures and monetary considerations at the instance of those in power, their henchmen and hirelings....”

The bench said that witnesses were the “eyes and ears of justice”, and if they were “incapacitated… the trial gets putrefied and paralysed”. If witnesses were “threatened or are forced to give false evidence”, the trial would not be fair, the bench said.

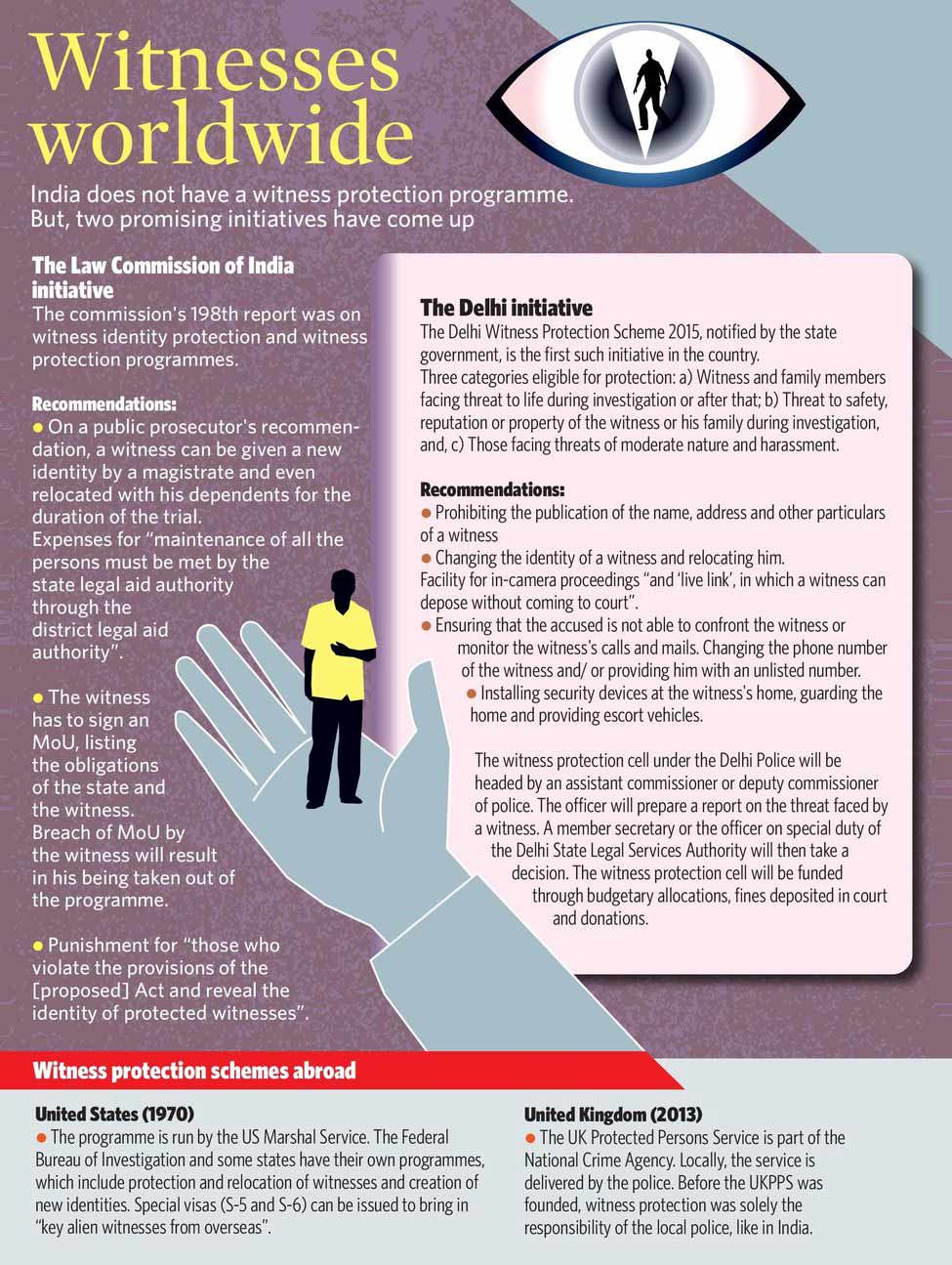

Perjury in the Jessica Lal murder case was most brazen. Shayan Munshi, star witness for the prosecution, is facing perjury charges after he changed his statement saying he did not know Hindi. Defence witness Prem Manocha is facing similar charges. Worried, the Delhi High Court directed the state government to frame a witness protection programme. In July, Delhi became the first state to notify the law. A special cell for witness protection has been set up.

The BMW hit-and-run case involving Sanjeev Nanda is just as sordid. Nanda had run over three policemen and three pedestrians, killing all. A sting by a television channel showed defence and prosecution lawyers asking eyewitness Sunil Kulkarni to change his testimony. The price? 05 crore. R.K Anand, the defence lawyer, was debarred.

The case about Varun Gandhi's hate speech in Pilibhit collapsed after 80 witnesses, including the journalist who recorded the event, changed their statements. In the speech, made on the sidelines of the 2009 Lok Sabha election campaign, Gandhi had allegedly threatened to behead people from a specific community.

The murder of witnesses in the Asaram case has revived the call for a witness protection programme in India. In 2006, the Law Commission's 198th report (see graphics) clearly said that such a programme was “necessary’’ to protect witnesses of “serious offences”.

The commission wanted more than police protection for witnesses. It suggested that the identity of those testifying be kept secret. Witness anonymity is especially helpful in cases where the accused does not know the witness. So far, anonymity is guaranteed only to witnesses in cases involving terrorism and national security.

The Delhi High Court toyed with the same idea. In 2013, it issued guidelines for recording statements of vulnerable witnesses. It defined a vulnerable witness as a person who was not yet 18. The court proposed in camera, video examination in sensitive cases. However, nationwide, witnesses continued to be intimidated, especially in cases involving murder and even communal riots.

Graphics: N.V. Jose

Graphics: N.V. Jose

While the imprint of the powerful may be visible in the verdict―think Salman Khan's hit-and-run case or even his black buck shooting case―the prosecution, too, is not above playing games. There are pocket witnesses, who will stick with the truth. Then there are the witnesses who will suddenly crop up in the middle of a case. In a Delhi bomb blast case, the Delhi Police sprang a surprise witness for the trial. This witness ‘identified’ the accused from the facial features. John says, “The idea is to win. The prosecution does the same.”

If the accused has political clout, then the threat to witnesses doubles. Ask Ajay Kumar Katara. If his identity was kept anonymous, he would not have had to live a marked life since February 2002.

It was peak winter in Delhi and the height of mayhem: marriage season. Ajay was returning home to Ghaziabad when his scooter broke down near the Hapur toll booth. It was past midnight and streets were deserted. A Tata Safari pulled up, asked him to move his scooter out of the way and sped off. There were four people in the Safari; in the back seat sat a fair, round-faced man in a red kurta. Three days later the round-faced man's charred body was found next to the highway. Ajay was the last man to see Nitish Katara alive.

An IAS officer's son, the 24-year-old Nitish was dating Bharati Yadav, daughter of D.P. Yadav, politician and mafia boss from Uttar Pradesh. Peeved by the relationship, Bharti's brother Vikas Yadav and cousin Vishal Yadav picked Nitish up from a wedding, which he was attending with Bharti, and hammered him to death. They ran into Ajay on their way back from the wedding.

As key witness, Ajay stubbornly refused to change his statement despite the defence trying to malign him and slapping cases on him. In the end, his statement won the case. The Supreme Court found the Yadav boys and Sukhdev Pehalwan guilty, and called Ajay's stand an act of “courage”.

“All witnesses had resiled and only this man recorded his statement against the accused,” the bench said. “His is a strange case. What kind of people are we? Even the girl in the case [Bharti] denies the relationship till it is established by her phone calls and cards sent to the boy. Everybody has resiled in the case.” Then, the bench complimented Ajay: “See the power you wielded.”

On the night of the murder, it was Bharti who woke up Neelam Katara, Nitish's mother, frantic with worry. There were friends who saw Nitish leave with the Yadavs. But, once the case began, it was as in the Agatha Christie book, Then There were None. Stories changed as witnesses were bought over; some refused to get involved.

“You have to remember, he was like a don,” says Ajay. “No one wanted to take him on. He controls thugs. Why would you want to become his enemy?” Neelam, who had led a rather sheltered life as a bureaucrat's wife, got a rude shock. “One by one, all the witnesses turned,” she says. “The UP policemen themselves changed what they said in court.” So, the burden of truth fell on Ajay Kumar Katara, no relative, just a stranger with a spine.

The defence did try to buy him off. He was promised a house in Goa and his parents were told that they would never have to worry about money again. Ajay has been intimidated, poisoned and fired upon, once when his security guards were with him. His security detail was given 050 lakh to look away. “After he threatened to kill me, I became even more determined to tell the truth. If I am going to die, I might as well tell the truth,” said Ajay. Despite the Supreme Court sentencing the Yadavs, the threat remains.

Unlike in the west, where being part of a jury is seen as a duty, being a witness in India usually means being summoned to court repeatedly. It takes years to record witnesses' statements and the compensation is paltry. In the Asaram case, the daily allowance given by the court to the victim's father is Rs.5.25.

“It is the most onerous and honourable task,” says Navkiran Singh, a Chandigarh-based lawyer. “In India, as a witness, you wait for hours if you are called for a statement. Usually, it is never recorded the same day. You do not have a place to sit, but the accused has. You often do not even get a glass of water.”

In the opaque and convoluted legal system, a witness is the foundation of a case. Says Mishra, “If we cannot gain and retain witnesses, how will the police ever build the case?”

Standing up in court to tell your story is far from easy. As the Supreme Court observed in Swaran Singh vs the State of Punjab: “A witness in a criminal trial may come from a far-off place to find the case adjourned. He has to come to the court many times and at what cost to his own self and his family is not difficult to fathom. It has become more or less a fashion to have a criminal case adjourned again and again till the witness tires and he gives up. Not only that a witness is threatened; he is abducted; he is maimed; he is done away with; or even bribed.”

Even in the fast-track court in Jodhpur, it took the victim three months to record her statement. The caseload for the judges is immense, so it often takes the witness more than one trip to the court to make a statement.

Sandal scandal: Bodies of suspected sandalwood smugglers who were killed in Seshachalam forest, Andhra Pradesh | AFP

Sandal scandal: Bodies of suspected sandalwood smugglers who were killed in Seshachalam forest, Andhra Pradesh | AFP

Former Bombay High Court judge Hosbet Suresh believes that in sensitive cases, such as sexual assaults, the statement given by the victim should be sealed. “The statement should be taken soon after the incident,” he says. “In Hong Kong, for example, there is a scheme where after the evidentiary statement of the victim is taken, she is given a new name, a new identity and a new job.” The victim does not need to come to court after that. “It also ensures high conviction rates. How can you expect the witness to clearly remember what happened years ago?”

The trauma of reliving the experience for years is far from healthy. For those testifying in riots and 'encounter' cases, the stakes are much higher. The Gujarat riots―and the flip-flop of Zahira Sheikh's statement in the Best Bakery case―emphasised the need for a witness protection programme. The court had ordered the Central Industrial Security Force to protect 117 witnesses appearing in the riot cases.

Sometimes, the so-called protectors become predators. Ilangovan, Balachandran and Sekar from Tamil Nadu have been living with the fear of death since the summer. The three witnessed the ‘encounter’ in which the Special Task Force of the Andhra Pradesh Police killed 20 sandalwood smugglers. Their accounts suggest that it was more of a massacre than an encounter.

Henri Tiphagne of People’s Watch, an NGO, has been keeping them safe in the organisation's office. The three are terrified to go back home, as they fear being rounded up by the police. “What they did was an act of courage,” Tiphagne says. In an attempt to ensure that their first statement was protected, Tiphagne produced them in front of the National Human Rights Commission. “Their version has to be given legitimacy. It has to be protected,” he says.

Over the next few months, the witnesses had to relive the terror of that night when “the police shot their friends”. They had to recount their story to the people who they were testifying against! They were taken down the same route by the police, to reconstruct the events. “They have to be produced by the AP Police in front of the magistrate to record their statement. They were surrounded by STF people and our first battle was to get their lawyers in,” Tiphagne says.

While the statements have been recorded, the state still has a right to recall the witness. “The problem will begin now that they are back in the village,” Tiphagne says. “They will be discouraged from telling their story by others. It is safer for them. Who wants to take on the police?”

And, fear is not the only weapon in the state's arsenal. There is another, more effective weapon: endless delay. As these cases drag for decades, witnesses who are not eliminated have their spirits crushed. The five survivors of Hashimpura massacre―where 42 men were rounded up and shot by the Army and the Provincial Armed Constabulary―have waited 28 years and are still waiting. Three accused have died, so has the information officer. And, the files have been lost. A Delhi trial court let the accused off because of lack of evidence.

“In majority of cases it takes so long to summon that the witness waits indefinitely,” says John. “How do you expect a witness to reconnect with the facts of the case? There are consequences of this endless wait, which have to borne by the witness.” Truth and justice do not count.