From exploring the Guatemalan and Belize jungles as part of a project trying to solve the Mayan mystery, to being the second American to go to the epicentre of the Tunguska meteorite crater in Siberia, Gibson, 58, has done it all.

“I talk with people in different time zones across the world. So, I do not know what day of the week it is,” he quips.

Right now, Gibson, who is reluctant to disclose his current location, is chasing one of the biggest mysteries in modern history: Flight MH370. What happened to the Malaysia Airlines flight from Kuala Lumpur to Beijing that disappeared on March 8, 2014?

“We need to find out to give answers to families of the people who went missing, as well as to the world,” he says.

Gibson is often seen in ‘MH370’ T-shirts. “One of them was purchased at the first commemoration [of the flight going missing] in Kuala Lumpur,” he says. “It was made by the families of the victims.”

The others were gifted to him by the families at the second commemoration in Kuala Lumpur. “They refused to accept money, and insisted on me taking them, including the one I am wearing right now—which says MH 370 The Search: Keep It On.”

Gibson started his “independent investigation” a year after the flight went missing. Discussions in Facebook groups intrigued him initially, but it was the first commemoration in Kuala Lumpur that made him embark on the mission.

“I was shocked when I realised that, even after a year, the officials were not searching the beaches, nobody had interviewed eyewitnesses, everything was based on Inmarsat satellite data, and they had found nothing,” he recalls. “Then when I heard Grace Nathan [spokesperson of Voice 370, a support group of crash victims’ families] speak about her mother, it sounded so much like the way I would speak about my mother.”

The solo search is no big deal, he says. “The truth is that it doesn’t cost all that much,” says Gibson, who does not have a wife or children. All that he takes with him on his sea expeditions is his phone, with which he records GPS readings and takes pictures.

The travel expenses, too, are modest. “For instance, when I went to the Maldives, I stayed at a $40-per-night inn; I do not stay at thousand-dollar resorts,” he says.

Gibson is grateful to the local communities that have helped him, and says he can sense if he is likely to find some debris “as soon as I get to a beach”. “If I see things like nets, buoys and plastic scrap that are coming from the Indian Ocean, I know there is a chance that there could be something from the plane, too,” he says.

Sign of hope: A woman leaves a message of support for passengers of the missing Malaysia Airlines Flight MH370 in Kuala Lumpur | Reuters

Sign of hope: A woman leaves a message of support for passengers of the missing Malaysia Airlines Flight MH370 in Kuala Lumpur | Reuters

The Aircrash Support Group Australia, which represents the families of the crash victims, invited Gibson to Australia and arranged for him to meet oceanographer Charitha Pattiaratchi (Dr Charie). He also met Deputy Prime Minister Warren Trust and other top officials engaged in the search.

“These are very sincere people, very seriously trying to find the plane,” says Gibson.

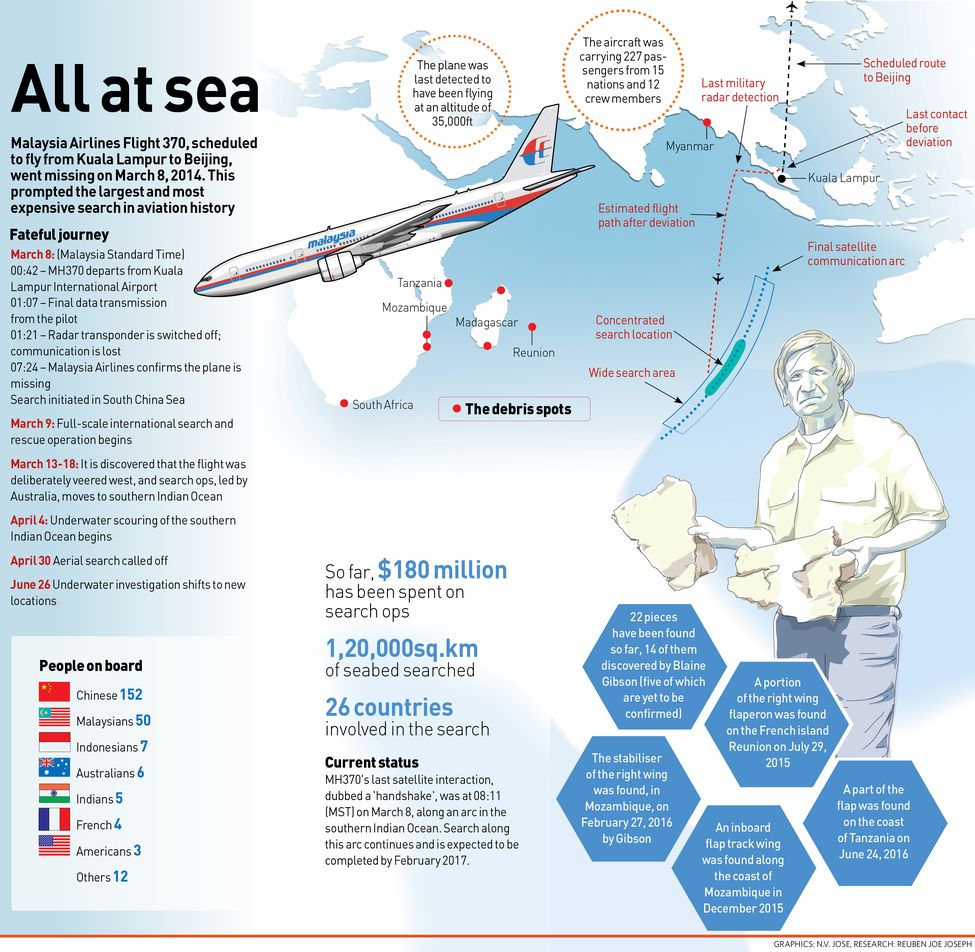

The discovery of the flaperon [a wing part used to stabilise aircraft] showed where the plane could have crashed. “We knew it was somewhere in the southern Indian Ocean, south of the Equator,” he says. “We have more than 22 pieces of debris [the last count given by the Malaysians, 9 of which are Gibson’s finds] in the southwest Indian Ocean. Everything is near Africa, nothing has been found in Australia or Tasmania.”

Gibson found the wing’s “No Step” panel in Mozambique in February 2016. That was the second piece of MH370 debris to be reported (the flaperon being the first). Incidentally, a South African teenager, Liam Lotter, who was holidaying in Mozambique, also discovered a piece of the aircraft’s fairing.

In June 2016, Gibson found five more pieces of debris on a beach in Madagascar. “That’s one beach, just 18km long,” says Gibson.

He went to that beach based on Dr Charie’s drift pattern clues. “It was clearly a hot zone,” says Gibson, who was surprised that nobody else went there.

Gibson handed over five pieces of debris to the Madagascar authorities. A Malaysian investigator was supposed to pick them up, but the plan, for reasons unknown, was cancelled, he says.

“The pieces are still sitting there,” says Gibson. “Malaysia recently said it will have its high commissioner pick them up. I hope that happens.”

On another beach 13km away, Gibson found three more pieces of debris. “I took two of them to Malaysia myself because they were small.”

The significance of the debris is that they indicate that the plane shattered on impact, says Gibson.

“Three are pieces from the interior cabin—one is the monitor case that goes around the TV at the back of seats... that is unmistakable. I saw that and tears welled up in my eyes,” he says. “One piece has the interior cabin laminate, the nice pretty little white pattern, and it is distinctive to Malaysia Airlines. These pieces prove that the cabin shattered on impact.”

These findings shatter the theory that the cabin could be intact on the seabed because of the pilot’s controlled ditching into the water, says Gibson.

“That was not what happened, period,” he says. “It was a high-speed impact, and it shattered the plane.”

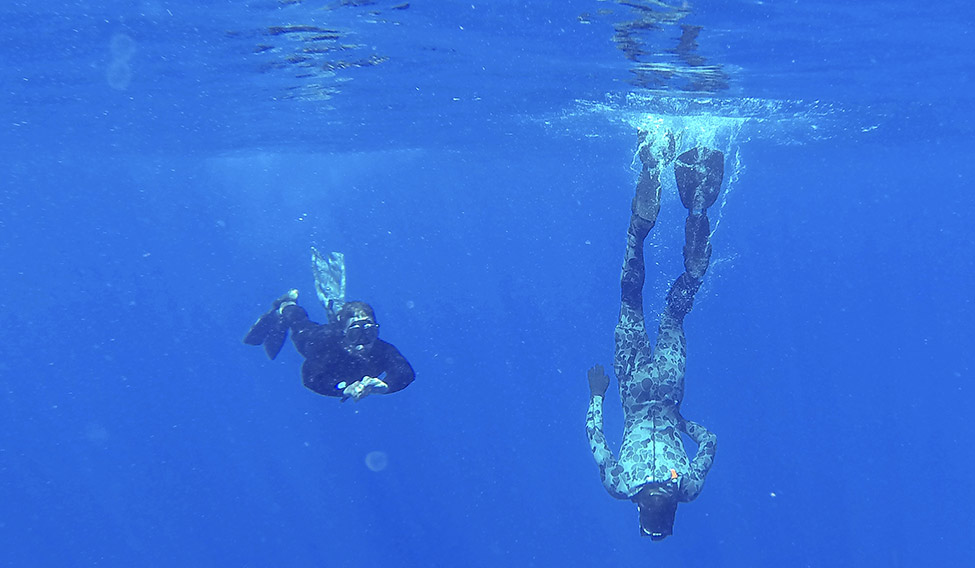

Deep Down Under : Australia has been in the forefront of the MH370 search operations. This 2014 photo shows Australian defence clearance divers scan for debris in the southern Indian Ocean. Up to 14 planes and as many ships focused on a single search area covering 77, 580 sq.km northwest of Perth. Sadly, no evidence was found in this region.

Deep Down Under : Australia has been in the forefront of the MH370 search operations. This 2014 photo shows Australian defence clearance divers scan for debris in the southern Indian Ocean. Up to 14 planes and as many ships focused on a single search area covering 77, 580 sq.km northwest of Perth. Sadly, no evidence was found in this region.

Doubts about Inmarsat data

Global experts have looked at this data and interpreted that the plane went southwards. Using certain assumptions, they identified a probable crash area.

“What if the satcom system was not operating perfectly?” he asks. “Even if you are off a little bit, you are off by a fairly large area.”

Gibson, however, says Inmarsat data is the best evidence available as of now. But there are limitations, he adds. “The satellite only knew how far the plane was,” he says. “It was not getting GPS coordinates transmitted back because Malaysia Airlines had not signed up for that programme.”

Gibson feels it is important to look at other evidences. “The debris and the drift analyses give us some clues,” he says. “Then, there are witnesses in the Maldives who saw a large, low-flying, jet plane that matched the description of MH370. If the eyes of the satellite are wrong, the eyes of the fishermen could be right.”

What about the article in Le Monde that claimed what the fishermen saw was a private jet?

“Oh, the fishermen are absolutely sure about what they saw,” says Gibson. “I have published the flight record from that morning. There was no domestic propeller plane flight flying there at that time.”

The article says the aircraft in question—Flight 149—was from Male to Thimarafushi, landing at 6:33am. “That flight did not exist, period,” says Gibson. “It was confirmed by the air-traffic controller.”

Gibson, however, clarifies that there is no proof that what the fishermen saw was, indeed, MH370.

“First, the Maldivian authorities said that there was no plane at all because their radars did not detect any aircraft. Then they said that it was a private jet, and rumours went out on the internet that it was the crown prince of Saudi Arabia [now the king], or Prince William and Kate Middleton,” says Gibson.

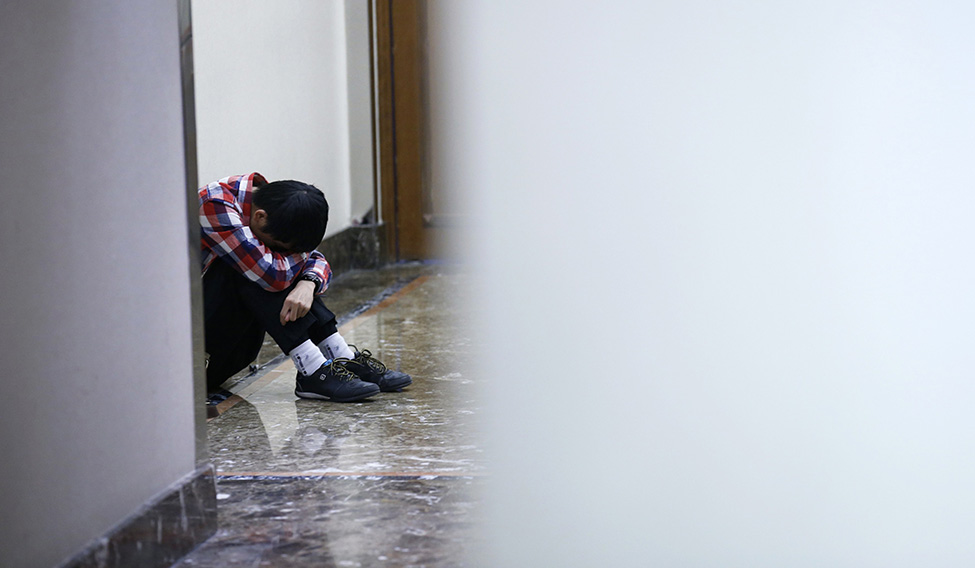

Great depression: An MH370 passenger’s friend weeps as he waits for news from Malaysia Airlines at the lobby of a hotel in Beijing in March 2014 | Reuters

Great depression: An MH370 passenger’s friend weeps as he waits for news from Malaysia Airlines at the lobby of a hotel in Beijing in March 2014 | Reuters

The Maldivian authorities did not detect the plane because they do not have any radar down there, he says. “Probably, they were embarrassed to say that a big plane could have flown over their country and they did not know about it.”

William and Kate flew in on a 747, a regularly scheduled flight—not a private jet—from London a couple of days earlier, says Gibson.

Similarly, the Saudi prince flew into Male airport in his 747, which did not go over Kudahuvadhoo, where the fishermen claimed to see the aircraft,” he says.

So, what did the fishermen actually see? “Mystery,” he says.

Gibson says he was well-received by the authorities and investigation team in Malaysia when he arrived with the pieces of debris. “The problem appears to be at the upper levels,” he notes.

Gibson, however, is all praise for the Australians. “They have been absolutely wonderful with the families of victims,” he says. “It was not their plane, but it is their search area.”

Australia invited the families and Gibson on board the search ship. “Those guys on that ship really care, they are really trying to find this plane,” he says.

A passenger’s relative wails in grief after a news conference in Kuala Lumpur | Reuters

A passenger’s relative wails in grief after a news conference in Kuala Lumpur | Reuters

Gibson has a set of detractors, too. In fact, there are people who allege his findings were “planted”. He dismisses such criticism as “absolutely preposterous”.

“The person who started the whole thing has a theory that the plane is buried in sand in Kazakhstan,” he says. “Another one has a theory that the plane crashed in the Gulf of Thailand. For them, it is about protecting their pet theories. For me, it is about finding the truth.”

Gibson laughs at the idea of him travelling around the world with Boeing 777 parts in his suitcase. “That is clearly character defamation,” he says. “I am a private citizen, spending my own money to try to find out what happened to this plane.”

He has also got some veiled threats. “I remember one of them saying, ‘No plane, no Blaine’,” he says. “I have learnt that there are agenda factories. There seem to be people out there who want to blame traditional enemies such as the US, Israel and the Arabs. There is a big list of conspiracy theories out there.”

Gibson says he is steadfast in his mission because he is making a difference. “And I am not going to give up,” he says.

Oceanic mystery: Australian air force personnel throw a self-locating data marker buoy from a C-130J Hercules aircraft during a search sortie over southern Indian Ocean | AFP

Oceanic mystery: Australian air force personnel throw a self-locating data marker buoy from a C-130J Hercules aircraft during a search sortie over southern Indian Ocean | AFP

The Indian connect

What makes Blaine’s efforts laudable is evident only when one speaks to the real sufferers in this mystery. THE WEEK met two of the three families of Indian victims that are yet to recover from the shock. (Samved Kolhekar, who lost his parents and younger brother, did not respond to repeated attempts to contact him.)

Kranti Shirsath

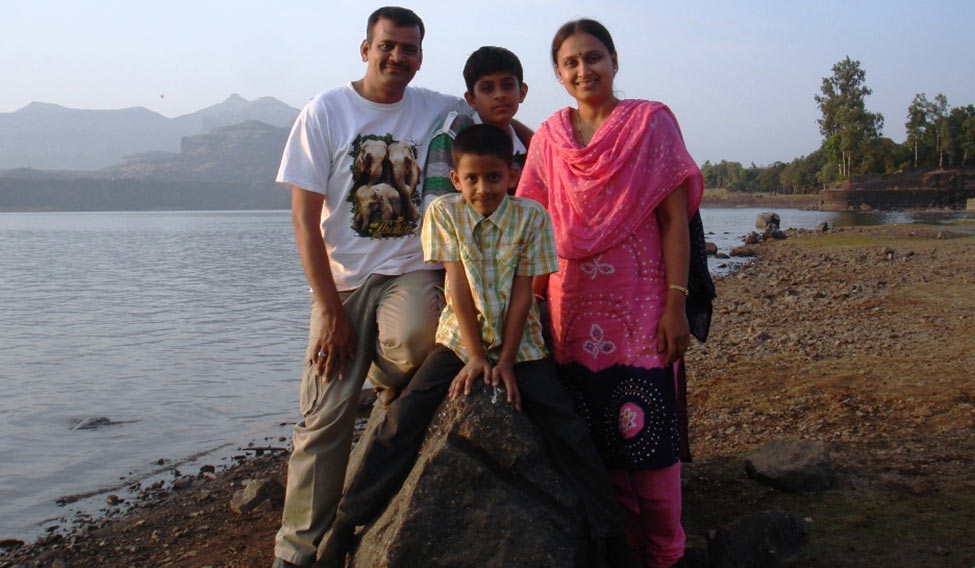

A 2012 family photo greets me as I enter Pralhad Shirsath’s spacious apartment in Pune. In the frame, Pralhad, Kranti and their sons Rahul and Yashwant (aka Kabir) are beaming, standing on the Great Wall of China.

The smile on Pralhad’s face now is different, strained. Rahul’s cherubic face has turned gaunt—he has dark, sunken sockets for eyes.

Rahul was 16 and Kabir 9 when their mother, a chemistry lecturer, boarded Flight MH370 to join Pralhad, who was then working in Pyongyang, North Korea.

“My mother had a long trip: Mumbai-Delhi-Kuala Lumpur-Beijing-Pyongyang. The last time we spoke was when she called from Mumbai to say bye,” says Rahul. “I wished her a happy journey.”

The next morning, Rahul had just woken up when his uncle called, telling him to watch news. “I got nervous,” he recalls.

Then he saw it: a Malaysia Airlines plane had “vanished”. “I could feel blood pumping through my veins, and then I fainted,” he says. “When I regained consciousness, I called my father. On hearing my voice, he broke down. That was when reality hit me—‘this is actually happening’. I frantically tried my mother’s number, but there was no response.”

On the night before, Pralhad had called Kranti to make sure she had boarded the flight; he was to pick her up the next morning. “Everything is okay... don’t worry, see you in the morning,” she said.

After the news broke, Pralhad used his connections in diplomatic circles and travelled by road and air to China. “In Beijing, Buddhist monks rushed to help the relatives of victims. They spoke fluent English and were well-trained to handle such situations.”

Back to base: Indian Navy ship INS Kesari, which was involved in search operations, returns to Port Blair | Reuters

Back to base: Indian Navy ship INS Kesari, which was involved in search operations, returns to Port Blair | Reuters

The Indian embassies—in North Korea, China and Malaysia—were very helpful, says Pralhad, who was the country head of Concern Worldwide in North Korea.

He quit the job and returned to India to take care of his children. He spends most of his time in Pimpalgaon, about 200km from Pune, where he grows bell peppers in a greenhouse. “This place has her memories,” he says. Now, all he seeks is “the truth, some conclusions”.

According to Inmarsat data, the flight was airborne for about eight hours after it disappeared from the radar. “If it flew over Malaysia and Indonesia, how come their surveillance systems did not spot it? Also, that means somebody was controlling that plane,” he says.

Even if there was a technical glitch, the Boeing 777 has six systems to communicate with the ground, notes Pralhad. “How can all malfunction at the same time?” he asks.

Pralhad, who slams the Malaysian authorities for their lethargic approach, has also been questioning them on the flight’s cargo. “We know that there were lithium-ion batteries for Motorola China as well as cartons of mangosteen. If there was a fire because of the batteries, the pilots would have placed distress calls,” he says.

Pralhad rules out pilot suicide or mass murder theories. “If the pilot wanted to commit suicide or mass murder, he did not have to fly for so many hours. Also, he could have crashed the plane into some prominent location and achieved a bigger result.”

Global politics could have been at play, says Pralhad. “In Kuala Lumpur, the relatives of missing Chinese victims kept saying that they had to be cautious as government spies were after them,” he says.

Pralhad also recalls a theory that North Korea had hijacked Flight MH370. “I have a hundred reasons to believe that because that country can do anything.... It is also capable of hiding that aircraft.”

Pralhad’s pain is palpable. He recalls an incident a few months after the tragedy. “At a birthday party, some games had been organised for children.

z The compere announced that a gift awaited the kid who ran to him first with his or her mother’s purse. Like other children, Kabir [who was just nine] darted in excitement, and then suddenly stopped. I was crushed.”

Pralhad says the trauma is far from reaching a closure. “Even now when I go to bed, I type MH370 on my mobile to get updates,” he says.

Chandrika Sharma

K.S. Narendran, a management consultant in Chennai, lost his wife Chandrika Sharma, who was on her way to Mongolia. She was the executive secretary of International Collective in Support of Fish Workers.

Good old memories: Pralhad Shirsath with wife Kranti, who was on Flight MH 370, and their sons during a holiday.

Good old memories: Pralhad Shirsath with wife Kranti, who was on Flight MH 370, and their sons during a holiday.

The couple had met at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences in Mumbai, and got close while working in Delhi. Narendran describes Chandrika as “a lively, animated person who had a tremendous zest for life”. “Yet, she had a seriousness revolving around larger social and environmental concerns,”

he says.

Narendran and daughter Meghna visited Kuala Lumpur, but “the trip didn’t answer any questions or offer new perspectives”, he says. “However, it was good to meet other families [of victims],” he says.

Did anyone from India contact him? “Zilch,” he says. “The incident took place in March, and the general elections were due in May. So it was not surprising.”

However, the Indian embassy in Kuala Lumpur has been in touch and “very helpful”, says Narendran.

Malaysia Airlines offers tele-support to the families, but the calls have a “call-centre quality to them”, he says. “Ask them questions, and they would flounder. Earlier, they called daily or once in a couple of days; now they call once a week.”

The situation is frustrating, says Narendran. “One wants a certain logical end,” he says. “The cases are in the court. Malaysia Airlines had offered $50,000 as the first instalment of compensation. Given the overall air of suspicion, one didn’t know what one was signing up for.... One was not in a hurry. Accepting it would be a tacit admission that it is all over.”

Narendran feels no big money has been spent on the search. “They have spent about $180 million, while a Boeing 777 costs about $300 million,” he says. “China—a big economy, which had the maximum number of passengers on that flight—has not contributed proportionately, and that is mysterious.”

Anguish and anger: K.S. Narendran of Chennai (right) lost his wife Chandrika Sharma (left), who, he says, had a “tremendous zest for life” | R.G. Sasthaa

Anguish and anger: K.S. Narendran of Chennai (right) lost his wife Chandrika Sharma (left), who, he says, had a “tremendous zest for life” | R.G. Sasthaa

Similarly, he wonders why all 14 countries, including India, whose citizens were on the flight, are not taking sufficient interest in the search.

Recently, he wrote to the ministries of external affairs and civil aviation, urging them “to be willing to fund the continuation of the search, to be counted as an interested player, to push Malaysia to deal with the debris on time and report back and to help the families to deal with the aftermath and other legal processes”.

No response yet, he says.

Narendran says, initially, he had many well-wishers around him. “But once the house empties out, one has to stare at the emptiness and it stares back,” he says.

Some things are irreversible, he says. “If I have to move forward, I have to be willing to let go of some things,” he adds. “I, however, am not yet willing.”