At the height of the Kargil war in 1999, prime minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee summoned the director-general (security) at the cabinet secretariat for a one-to-one, hush-hush meeting. He had one question for the officer: Did he have men who could carry out an operation near Pakistan’s nuclear facility in Kahuta, located in the Himalayan foothills in their part of Punjab?

Soon after the meeting, a band of 40 bearded men in plainclothes left their base at Sarsawa in Saharanpur district in Uttar Pradesh for a remote location in Jammu and Kashmir, the terrain of which was similar to that of Kahuta. The men were part of the Special Group, India’s most elite special forces unit that was so discreet that it was considered nonexistent. Their objective: train for a suicide mission. “For almost 45 days, the men were made to run up and down the hills for the mission, which did not happen ultimately,” an intelligence officer who monitored them from Delhi told THE WEEK.

Months later, in December, the same men were placed on standby again. Terrorists had hijacked the Indian Airlines flight 814 and forced it to land in Kandahar in Afghanistan. Thanks to the efforts of officers of the Research and Analysis Wing, Iran had agreed to provide five helicopters for a planned strike on the hijackers.

Ajit Doval, the current national security adviser, was then in the Intelligence Bureau and was involved in coordinating the mission. The operatives were told to kill the Taliban members surrounding the plane, and make way for a crack team of the National Security Guard to storm the aircraft. “However, the mounting pressure from the families [of hostages] and television channels forced Vajpayee to take a call against the strike,” said the intelligence officer, who, at that time, was working closely with the Prime Minister’s Office. “Unlike today, we had the capability to strike back. The political leadership had the option of using a fully capable and proven strike force.”

The situation that India finds itself in, after the attack on the 12 Brigade headquarters in Uri in Jammu and Kashmir on September 18 this year, is very different from the crises in 1999. Perhaps, a parallel can be drawn between now and the situation after the November 2008 attacks in Mumbai. On the midnight of December 24 that year, the men, women and children in the border villages near Jodhpur in Rajasthan began packing their belongings to leave their homes for good. The reason: They had just witnessed fireworks like never before, and it wasn’t Diwali.

In New Delhi, a phone call woke up M.L. Kumawat, then director-general of the Border Security Force. On the other end of the line was an intelligence officer of the specialised G-branch of the BSF. “The villagers are leaving,” said the officer. “They say there has been a build-up of force on the Pakistani side and that the government is asking them to vacate their homes.”

Kumawat realised that the fear of war had gripped the villagers. He called officials at All India Radio and asked them to put out an announcement. “No communication has been received either by the BSF or the Rajasthan government for vacating any village along the border,” he said. “Such reports are designed to create panic where there is none.”

The following morning, the Union home ministry swung into action. Officers in forward posts were told to stamp out rumours of war, as the government knew the cost of escalating the border tension. “Once it starts, it is difficult to stop the firing,” Kumawat told THE WEEK. “One small incident can trigger a warlike situation. We can’t go by public outcry. I am glad that the Narendra Modi government has opted for a mature response.”

India’s response to the Uri attack has certainly been mature, with the government focusing on strategic and diplomatic offensives to isolate Pakistan. An all-out war has been ruled out, but plans of a more subtle kind are afoot. Intelligence officers are exploring the possibilities of carrying out covert, precision strikes on terrorist camps in Pakistan-occupied Kashmir. Maps have been pulled out to mark coordinates of locations like 26/11 mastermind Hafiz Saeed’s proposed gathering in Karachi and the Jamat-ud-Dawa headquarters in Muridke near Lahore. The JuD is believed to be the parent organisation of Lashkar-e-Taiba, which carried out the Mumbai attacks.

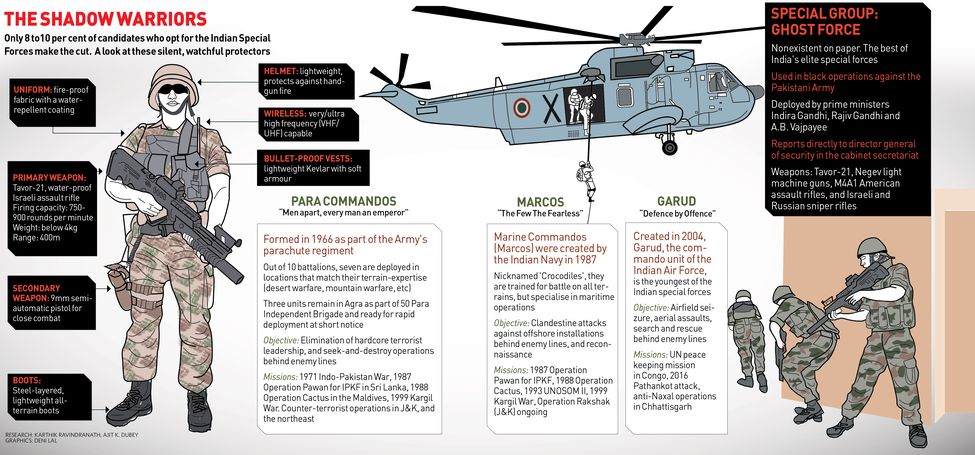

India certainly has the resources, at least on paper, to carry out covert strikes in PoK (see graphics). But the question is which of the special forces should go in, and whether they are prepared enough. Given the circumstances and the terrain involved, the Special Group appears to be the obvious choice. The SG personnel are well trained and well equipped, and have proved their mettle both on foreign soil and within India. SG, based in Sarsawa in UP, was used extensively by prime ministers Indira Gandhi, Rajiv Gandhi and Vajpayee for special operations in Kashmir and Punjab.

Staffed mostly by Para (Special Forces) officers of the Army, SG is directly under the command of the prime minister. “We were the first ones in the country to use AK-47 rifles, which were imported clandestinely from a European nation,” a former SG operative told THE WEEK.

SG’s list of successful ops is long. In the late 1980s, after Gen Hussain Muhammed Ershad captured power in Bangladesh, he held a political opponent in captivity. Even her life in prison was under threat. “The political personality was brought out from there by the Special Group under direct orders from the [Indian] prime minister,” said a source.

SG has also been used for black ops abroad. During the Indian Peacekeeping Force’s operations in Sri Lanka’s Tamil stronghold of Jaffna, SG provided training to members of the militant Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam. The force was also involved in Operation Blue Star to flush out terrorists from the Golden Temple in Amritsar. Former SG operatives say that even though the 1 Para (SF) of the Army claimed that it had killed militant leaders J.S. Bhindranwale and his military chief, Maj Gen (retd) Shabeg Singh, their bodies were riddled with AK-47 bullets. Only SG used AK-47 then.

As home minister, L.K. Advani used SG to eliminate militants in Kashmir. “Both he and defence minister George Fernandes would visit the headquarters in Sarsawa to personally congratulate and encourage the men who were carrying out successful operations at short notice, away from public glare, and sometimes even beyond the boundaries of our country,” said the senior officer.

SG, however, has lost some of its bite in recent years. A senior Army officer who served in SG said the curtailing of funds for intelligence gathering and deep operations had affected the force. Apparently, the feud between Gen V.K. Singh, when he was Army chief, and his junior colleagues, had severely constrained the intelligence gathering capabilities of the Army. In 2012, post Singh’s retirement, the top-secret Technical Support Division led by Colonel Hunny Bakshi was disbanded.

Covert ops, such as the ones that India is considering in PoK, require the right mix of technology, equipment and actionable intelligence to succeed. But, with intelligence gathering in disarray, it remains doubtful whether India has it.

Call to arms: Militants raising anti-India slogans in Muzaffarabad in Pakistan-occupied Kashmir | AFP

Call to arms: Militants raising anti-India slogans in Muzaffarabad in Pakistan-occupied Kashmir | AFP

To dismantle the terror infrastructure across the border, the special forces would first need to pin-point the location of terrorists. “We know these terror camps are not in pucca buildings,” said a former R&AW officer. “Often the satellite images give locations that are actually school buildings. How do we target them in such a case? Unless someone tells us where and when, it is very difficult to think of an aerial strike. If we send special forces to a pin-pointed location, we need to have deniability…. In case our man is caught, we lose all our credibility.”

Here is where moles and sources across the border become important. Till a few years ago, not even half a dozen cross-border sources or assets were available to Indian intelligence agencies. “We need to run our sources in the enemy territory and they should be able to carry out these operations by themselves,” said an officer of a border guarding force.

There is also the argument that the option of covert strikes within Indian territory is not well explored. “Covert operation does not necessarily mean that you have to cross the border,” said K. Srinivasan, former inspector-general who had worked in the intelligence wings of the BSF and the Central Reserve Police Force. “Along the border, there are a lot of elements who act as the support base for terrorists…. If we stamp out these elements, we can cut the oxygen supply of the terrorists.”

If the agencies know this formula, why do they fail to implement it? The answer takes us back to the basics. The demand of the intelligence wings for surveillance and interception capabilities has been pending for years. Currently, only law enforcement agencies and the Intelligence Bureau are allowed to intercept calls. The intelligence units of the forces deployed in Kashmir depend on other agencies for it. “As a result, there is a huge time lag, which is a big handicap for the troops on the ground. Any kind of covert operations cannot be carried out if real-time information is not available,” said an intelligence officer.

According to former home secretary G.K. Pillai, combining goodwill gestures with covert operations in conflict zones will increase manifold the chances of success. “Pakistan is carrying out aerial strikes in Balochistan. We have always enjoyed local support there but did not build on it. It is important to build on that goodwill today,” he said.

Kumawat cautions that while carrying out covert operations against Pakistan, New Delhi must keep in mind that it is in conflict with Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence and its military, and not its people. “If the people of Pakistan start feeling that the army and the non-state actors are not working in their interest, that will be our biggest victory,” he said.

Covert ops, however, do not offer a permanent solution to a problem that has festered over many decades, said Pillai. “Kashmir is the key,” he said. An officer who was part of many successful covert operations in the valley said if tourism is brought back, sports take place and development embraces Kashmir, India can even think of holding a plebiscite in the state. Will Pakistan hold a similar plebiscite in PoK? That day the war will be won.