Four years ago, when Ratan Tata decided to hang up his boots after an illustrious tenure as chairman of Tata Group, the salt-to-software conglomerate started a headhunt for his successor. Cyrus Mistry, a member of the Tata Sons board by virtue of his father Pallonji Mistry's 18.4 per cent stake, was part of the committee that was formed to find Tata's successor. During the selection process, however, Mistry impressed the other members of the committee so much so that they decided not to look any further.

Mistry had proved his mettle as managing director of his family firm Shapoorji Pallonji and Company, and had served as director of Tata Elxsi and Tata Power. His father's clout in Bombay House, the Tata Group headquarters, also helped in no small measure in his selection. Mistry was only the second chairman—after Nowroji Saklatwala, who led the group from 1932 to 1938—of the 144-year-old group to not bear the Tata surname.

Saklatwala had had the shortest term as Tata chairman, which was interrupted abruptly when he died of a heart attack in 1938. But on October 24, Mistry's term turned out to be shorter, when Tata Sons announced that its board had replaced him and given charge to Ratan Tata as interim chairman.

Few people had seen it coming. But within minutes theories started emerging, postulating the reasons for the sudden decision. Many of them attributed it to the lacklustre performance of some Tata Group companies, and some others to Mistry's handling of crucial issues like the dispute with NTT DoCoMo and Tata Steel's sick assets in Europe. Then there was talk on a clash of culture between the old guard and Mistry's methods.

It was in 2009 that NTT DoCoMo partnered with Tata to form Tata Teleservices. As many of its performance goals were not met, the Japanese partner decided to exit the alliance in 2014, and wanted the Tatas to either find a buyer for its 26 per cent stake or buy it out. Tata could not find a buyer and did not buy back the DoCoMo share. In January 2015, NTT DoCoMo filed an arbitration case. In June this year, the London Court of International Arbitration ordered Tata to pay $1.17 billion in damages to NTT DoCoMo. The case is currently being heard by the Delhi High Court and courts in the US and the UK. It is said that Ratan Tata was unhappy about how the issue was dragged to court.

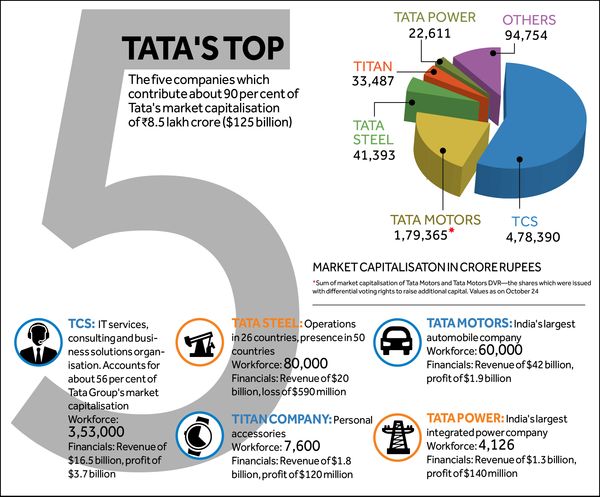

It is no secret that many of the Tata Group companies are struggling. Only two of its big ten businesses have done well in the recent past—the IT services giant Tata Consultancy Services and the carmaker Jaguar Land Rover, which it acquired from Ford in 2008. These two companies contributed more than 80 per cent of the group's total profit last year. In fact, TCS's fantastic run on the stock markets in the past decade has been the only reason behind Tata Group's stupendous growth in value during the period.

The lemon in the basket has been Tata Steel, once a flag-bearer of the group. Its $13.1 billion acquisition of the Anglo-Dutch steelmaker Corus in 2007 was part of Ratan Tata's ambitious global push. It made the company one of the biggest steelmakers in the world, but it soon became a victim of circumstances, as commodity prices started falling by 2012. Corus was burning money—according to some reports, as much as $1.3 million a day at one point. Tata was slow to react, and took years to figure out a way to stem the losses. In April this year, it sold the long products business in the UK to Greybull Capital for a token sum. And the company has been talking to the likes of ThyssenKrupp for a joint venture.

To be fair on him, Mistry inherited these losses. And he tried in his own way to fix it by getting out of it. But that was not the Tata way of doing business, and did not seem to have gone down well with the former chairman. Mistry, in fact, had made a number of asset sales during his tenure to bring down the debt burden. In 2014, Tata Power sold 30 per cent stake in its coal mine in Indonesia for Rs 3,100 crore. In April this year, Tata Chemicals sold its urea plant in Uttar Pradesh to a Norwegian company for Rs 2,600 crore. In May, Tata Communications sold the majority stake in a data centre it owned. In June, Tata sold Neotel, a telecom company it owned in South Africa, for Rs 3,000 crore.

There is an argument that rather than what Mistry sold, it was the one big purchase that he made sealed his fate. In June, he finalised Tata Power's acquisition of Welspun's solar farms for $1.4 billion. It was said to be without the approval of Ratan Tata and other key shareholder. And, that was not how business had been done at Bombay House.

It does not take much to figure out that Ratan Tata was not happy about what was going on and he wanted to change it. And the decision to remove Mistry was anything but sudden. In August, Tata Sons board inducted Ajay Piramal of Piramal Enterprises and Venu Srinivasan of TVS. It is said that Mistry, who chaired the board, was not aware of these appointments, which clearly showed the discontent between the chairman and the major shareholder, Tata Trusts.

Up in arms: A protest after the loss of 900 jobs at the local Tata Steel works in Scunthorpe, northern England. Ratan Tata is likely to revist the plan to disinvest the sick units | AFP

Up in arms: A protest after the loss of 900 jobs at the local Tata Steel works in Scunthorpe, northern England. Ratan Tata is likely to revist the plan to disinvest the sick units | AFP

With about 66 per cent stake, Tata Trusts (Sir Dorabji Tata Trust and the allied trusts, and Sir Ratan Tata Trust and Navajbai Ratan Tata Trust) control Tata Sons, the holding entity of the companies in the Tata empire. Ratan Tata is the chairman of the trusts.

Cyrus Mistry's father, Pallonji Mistry, owns 18.4 per cent. He inherited 12.4 per cent from his father, Shapoorji Pallonji, and the rest through rights issue. Shapoorji Pallonji bought the shares from the heirs of F.E. Dinshaw, who was a friend and financier of the Tatas and got the shares in lieu of the money the Tatas owed him. Tata group companies own 13 per cent, and Tata family members and others own the rest.

Tata Sons chairman and Tata Trusts chairman have almost always been the same person. There has been only one exception earlier—for a short period, J.R.D. Tata headed Tata Trusts when Ratan Tata was Tata Sons chairman. So Mistry had always been under the threat of Ratan Tata flexing his muscles.

But, what made Ratan Tata sack Mistry, his handpicked successor, in such an unceremonious way? “A graceful exit option was offered to Mistry,” said a person close to Tata. “He was asked to step down, but he did not.” It seems Mistry was keen on facing the board. The board had nine members, including Tata and Mistry. Six of them are said to have voted for removing Mistry and two abstained. (On October 25, a day later, Tata Sons inducted JLR CEO Ralf Speth and TCS's N. Chandrasekaran to its board.)

While the insiders had been contemplating their options for months, industry watchers were clueless about a possible leadership change. “The decision came as a shock,” said market expert Ambareesh Baliga. “Now the battle lines will be clearly drawn. I don't think they (the Mistrys) will take it lying down.”

Though there has been speculation on Mistry taking a legal recourse, Shapoorji Pallonji Group did not confirm it. “While the circumstances are being studied, there is no basis to media speculation about litigation at this stage,” said a statement from the group. But in a letter to the board written on October 25, Mistry criticised the decision to remove him, calling it “unique in the annals of corporate history.” He alleged he had not been given freedom to manage the conglomerate.

Interestingly, Mistry's attempts to micro-manage the companies in the group was one thing that the directors and Ratan Tata were not comfortable with. They wanted the chairman to be a grand visionary, rather than someone who nitpicks over tiny details. Many insiders, especially some members of Tata Trusts, were aghast at Mistry's bookkeeping ways and the eagerness to collect the last rupee.

The trusts were not in sync with the high-profile Group Executive Council that Mistry set up with the intention of centralising the group's management. Even the CEOs of many group companies were not happy with the GEC. “Tata CEOs were used to running their companies independently under the guidance of Tata Sons,” said a Tata executive who did not want to be identified. “They did not take kindly to the interference.” The GEC was disbanded after Mistry was removed. At least three members of the GEC are said to be on their way out.

Despite the criticism that he deviated from the 'Tata way' of doing things, many measures that Mistry took were essential for the financial well-being of the group. In the letter to the directors, he had warned that the group might face $18 billion in writedowns because of five unprofitable businesses. According to an analysis by Edelweiss Capital, Mistry's focus on sale of assets which either were not profitable or were creating little shareholder value was hailed by the shareholders.

Mohandas Pai, chairman of Manipal Global Education Services and Aarin Capital, was disappointed by the way Mistry was treated by the Tata Sons board. “What has happened is wrong, as the legitimately appointed chairman of one of India’s largest industrial groups has been dethroned by other directors who succumbed to the pressure of a dominant shareholder, ignoring their fiduciary responsibility to 100 per cent of shareholders. If the dominant shareholder wanted a change in the leadership an extraordinary general meeting should have been called,” he said.

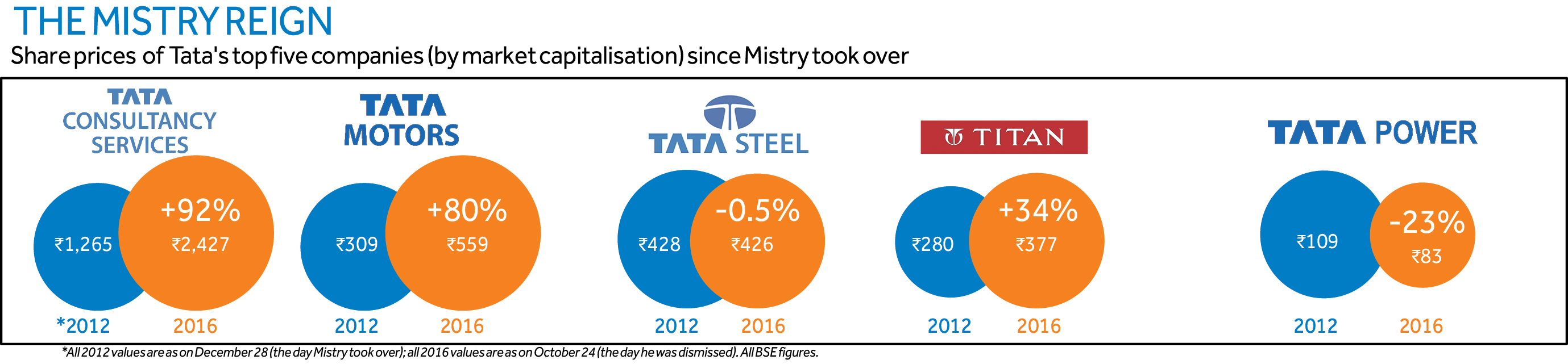

Under Mistry, the net profit of TCS jumped about 75 per cent, and its stock price rose 60 per cent. The revenue of Tata Motors grew 46 per cent under him, and its profit was up 11.4 per cent. “The company has had relative success in the passenger vehicles segment with the Tiago hatchback. But the company still has low capacity utilisation in this vertical, particularly at the Sanand unit. Nonetheless, Tata Motors has made a start with the Tiago finding favour with customers,” said Amit Sharma, senior research analyst (automobiles) at IHS Markit.

The markets, unsurprisingly, reacted strongly to the change. A day after Mistry was ousted, shares of all listed Tata companies except Tata Teleservices fell. Indian Hotels, Tata's hospitality arm, was the worst hit with a 3.16 per cent decline. Its share value had doubled during Mistry's tenure, as market participants had reacted positively to his attempts to sell its loss-making properties.

That means it will be difficult for Tata to undo everything that Mistry had done. However, in his first meeting with the heads of group companies, Ratan Tata hinted that some of Mistry's decisions might be reviewed. “We will evaluate and continue to undertake those that are required,” he said.

It is speculated that Tata will reverse the decision on the proposed sale of Tata Steel's Port Talbot unit in the UK. In fact, the British media has already said Mistry's removal was good news for the 11,000 UK workers of Tata Steel. They have been facing uncertanity ever since Mistry initiated a plan to sell sick assets.

Also, the dispute with NTT DoCoMo is likely to be settled soon. It was Tata who had promised the Japanese firm to pay half the amount of its investment if it left the business making a loss. He was said to be upset with Mistry's tough stand in the dispute. There are also reports that Tata may get out of the telecom business.

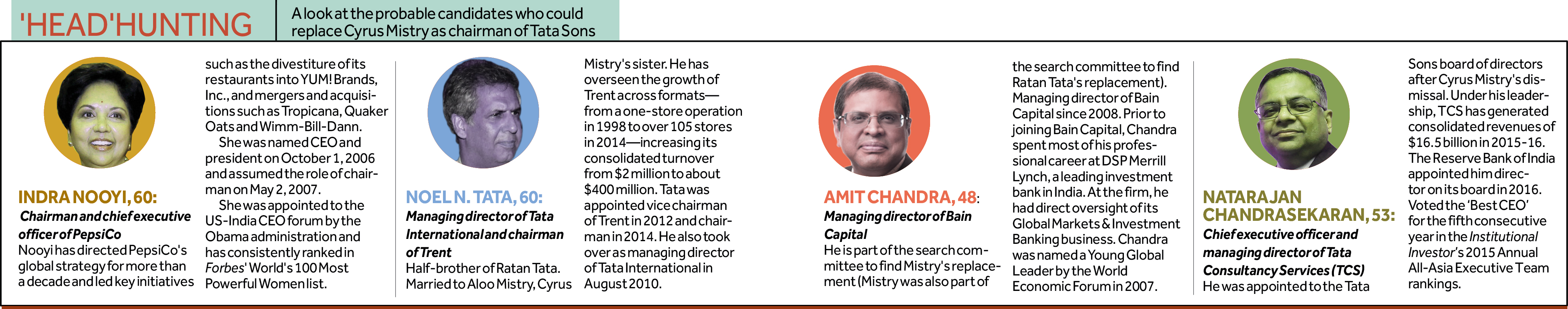

A bigger challenge for Tata would be finding a successor. He has made it clear that he had assumed the role of interim chairman for stability and continuity. “This will be for a short time,” he said. “A new permanent leadership will be in place.” The failed experiment with Mistry has made the job all the more difficult. Names like Indra Nooyi of PepsiCo, former Vodafone Group CEO Arun Sarin and former Deutsche Bank head honcho Anshu Jain are doing rounds. The frontrunner, however, seems to be TCS's Chandrasekaran.

The interim chairman and the next chairman cannot forget the fact Tata Group's problems pre-dated Mistry's tenure. Mistry tried to fix them in earnest, though not necessarily the way Tata would have liked. The next chairman will face the same challenges, but will have the opportunity not to repeat Mistry's 'mistakes'.

WITH ABHINAV SINGH AND RACHNA TYAGI