Mama tied a blindfold over my eyes. The next thing I felt was my flesh being cut away. I heard the blade sawing back and forth through my skin.

Waris Dirie, in Desert Flower: The Extraordinary Journey of a Desert Nomad

Aarefa Johari, 28, from Grant Road, Mumbai, has not read Dirie’s autobiography. Yet she can relate to what the Somali supermodel and actor would have gone through when she was cut. Johari, too, was circumcised by a midwife with a razor blade at the age of seven. “I was not given anaesthesia,” she says. “My mother ensured that only a bit on the tip of my clitoris was cut. Still, it was painful.” She was upset with her mother but eventually forgave her.

“She got it done on me thinking it was beneficial for me and necessary as per our tradition,” says Johari, a journalist with scroll.in.

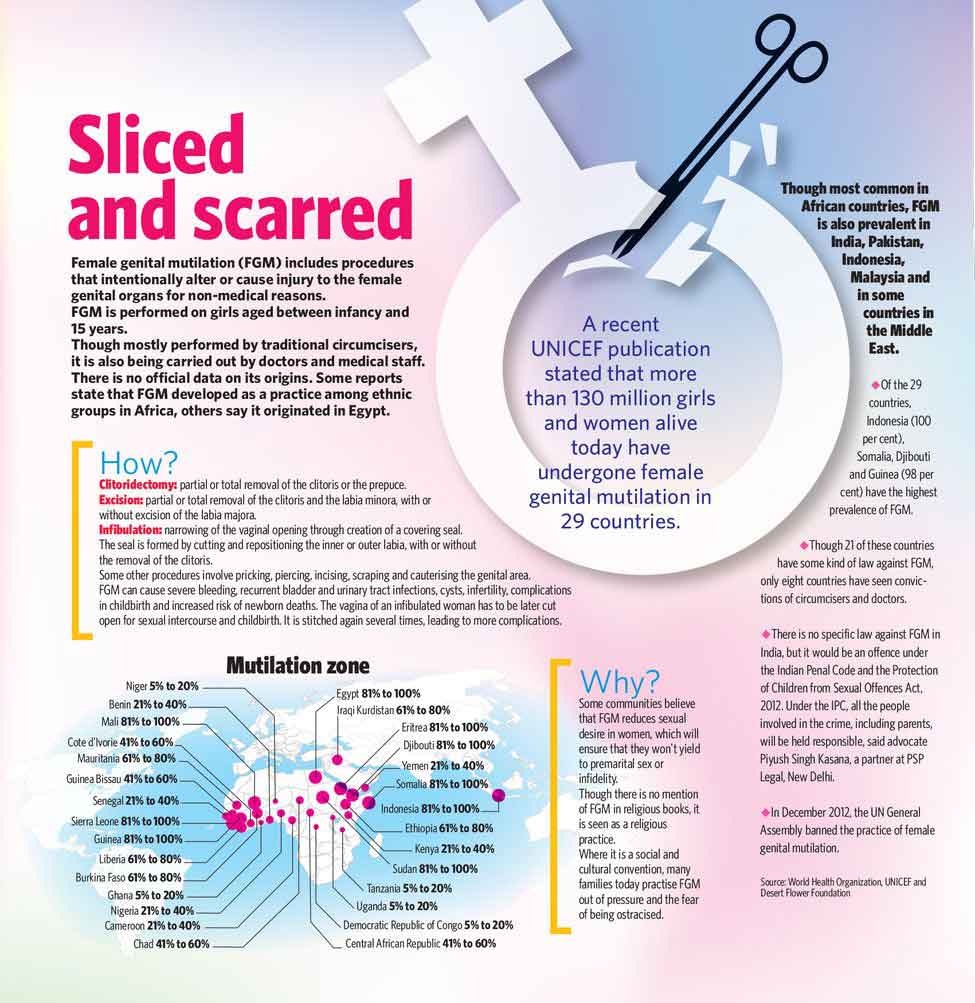

Female genital mutilation (FGM) or female circumcision, according to the World Health Organization, includes procedures that involve partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, or injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons. A recent UNICEF report states that more than 130 million girls and women alive today have undergone FGM in 29 countries where the practice is prevalent. As many as 30 million girls are at risk of being cut before their 15th birthday if the current trend continues. Most survivors are from African countries, but FGM is also practised in India, Pakistan, Indonesia, Malaysia and some countries in the Middle East.

FGM involves four procedures. What is practised in India is type 1, which involves partial or total removal of the clitoris or the prepuce. The other types of FGM include partial or total removal of the clitoris and the labia minora; narrowing of the vaginal opening; and other procedures like pricking, piercing, incising, scraping and cauterising the genital area.

FGM, which has been outlawed in many countries as a serious violation of human rights, is still prevalent among the Dawoodi Bohra community in India. An educated and affluent group of people, Dawoodi Bohras are a sub-sect of Ismaili Shias. India has a rough estimate of 5 lakh Bohras―around half of the 10 lakh-strong Bohra community in the world―spread across Maharashtra, Gujarat and Rajasthan. Around 90 per cent of Bohri women still undergo the archaic ritual.

survivors of FGM, also known as khatna among Bohris, often compare it to rape. For Johari, who belongs to the same community, the response to the trauma has been more of outright anger. She says the intention has been to moderate pleasure. “That is what the Bohris have been told for years,” she says. “Cutting is done with the objective of subduing a girl’s sexual urges. Basically, the belief is that if you get your daughter’s circumcision done, she will not have premarital or extramarital affairs. I cannot understand why and how the community allows this to be done or how anybody can justify this.”

Johari lives with her grandparents and mother in a 98-year-old building, which offers a panoramic view of the city. As her grandfather, who had gone out for a walk, steps into the house, she pauses for a moment to offer him some water and then continues the conversation. “Clitoris is the pleasure centre of the female body. What I have learnt from gynaecologists is that the entire area has a lot of erectile tissues. There have been many cases in India where the entire clitoris was cut,” she says.

RESEARCH: SUSAMMA KURIAN; GRAPHICS: N.V. JOSE

RESEARCH: SUSAMMA KURIAN; GRAPHICS: N.V. JOSE

In India, khatna used to be carried out by traditional practitioners with no medical training. Nafisa Lokhandwala, 58, from Kalupur in Ahmedabad, remembers how she would assist her grandmother while she performed khatna. Though she knows the procedure, Nafisa has never practised it. Those who undergo khatna would be advised not to have sour food for a day or two. But they would be given lots of lemonade. “Dadima [grandma] used to make natural antibiotics in her kitchen,” says Lokhandwala, a BSNL employee. She was circumcised when she was seven years old. Her granddaughter Yakut is now five. When Nafisa told me that Yakut is four, the little one prodded her, showed her five fingers and smiled. Two years from now, Yakut will also be circumcised. “All Bohris get it done without fail,” says Lokhandwala.

Priya Goswami

Priya Goswami

Khatna is generally done at the age of six or seven―the age when a girl is “old enough to remember what she went through and young enough not to question it”, says Priya Goswami, director of A Pinch of Skin, a documentary on genital cutting that won special mention at the 60th National Film Awards. She says FGM is practised by Bohras settled abroad, too. “There are a lot of expatriate Bohras, settled in developed countries, who get their daughters to fly back to India to undergo genital cutting,” she says. “They do have an understanding that something is not right about it and that it is increasingly coming under the illegal arena.”

The girl is taken for khatna under the pretext of buying an ice cream or going to a birthday party. Dr Farida Calcuttawala still remembers how her aunt dressed her up the day she was circumcised. “I thought something nice was going to happen. I was told that we were going out,” she says. She was taken to a house, which looked unhygienic, in a crowded Bohri locality and was given something to eat. An old, fat Bohri woman cut her. “Then people suddenly pulled me down. Whatever they had to do, they did it. It was horrible,” she says. Usually, it is the mother who takes the girl for khatna. But Calcuttawala’s grandmother went with her, as her mother couldn’t see her go through it. “My dadima was an illiterate but strong-willed person. She would control all these things. My mom didn’t have a say in it,” she says.

At a clinic on a narrow street near Bhendi Bazaar in Mumbai, we met a midwife who does genital cutting. Fragile and pale, she didn’t really appear to be a ‘cutter’. “She does it at her home and in the clinic,” says the Bohri woman who accompanied us. The midwife was tight-lipped about what went on in the clinic, as she had been forbidden to speak about it by the doctor and the religious heads.

On further investigations, THE WEEK found that genital cutting is also done in premier multispeciality hospitals in metro cities. We got in touch with a gynaecologist in a Bohri-run multispeciality hospital in Mumbai, posing as relatives of a Hindu woman who was forced by her Bohri mother-in-law to undergo FGM. A woman married to a Bohri is expected to undergo circumcision in order to be considered a Bohri. “There won’t be blood loss or pain. Only a pinch of the clitoris is removed, that, too, under anaesthesia. The person has to be in the hospital for 4-6 hours only,” says the gynaecologist.

The procedure costs Rs15,000. When I tell the gynaecologist that we friend cannot afford it, she brings it down by Rs1,000. “The anaesthetist needs to be paid. Then there are hospital charges. Also, we use better quality suture so that the one doesn’t feel any discomfort after the procedure,” she says. Cutting is done in the hospital on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Fridays.

Nafisa Lokhandwala underwent circumcision when she was seven years old. Her granddaughter Yakut is now five. Lokhandwala is planning to get khatna done on Yakut once she turns seven. "All Bohris get it done without fail,’’ she says | Mini P. Thomas

Nafisa Lokhandwala underwent circumcision when she was seven years old. Her granddaughter Yakut is now five. Lokhandwala is planning to get khatna done on Yakut once she turns seven. "All Bohris get it done without fail,’’ she says | Mini P. Thomas

Khatna can be performed only after a sanction from the religious head. “A list is given out; you are supposed to go to those doctors only,” says Aiman Kanchwala, 30, who got cut at the age of seven. “I don’t know how the network operates or how the list is circulated. It is a well-guarded information.”

Rukaiya Master, 17, from Sunel, a small town in Jhalawar district in Rajasthan, says that every Bohri girl should undergo khatna, as it is a religious practice. She underwent it when she was seven. Islamic scholars, however, say that there is no mention of any type of genital mutilation in the Quran. “Religion has nothing to do with it,” says Dr Zeenat Shaukat Ali, professor of Islamic Studies, St Xavier’s College, Mumbai, and director of The Wisdom Foundation. “These are customary practices of certain traditional societies in some parts of Africa, where all women were genitally mutilated irrespective of their religion, caste or creed. Among them, there were Muslims, too.” They continued to follow it even after migrating to other countries. Bohris started practising it as they got converted to Islam. The objective of the practice, says Ali, is to subdue women emotionally and sexually.

“I think when you are part of a community, you need to follow certain practices,” says Tasneem, who runs a small boutique in Viramgam, Gujarat. Tasneem has three daughters. The elder ones, who are now 14 and 10, underwent khatna. The younger one, at a year and a half, is too young for it.

Unlike male circumcision, khatna is a hush-hush affair. Bohris don’t talk about it. Some of the men in the community don’t even know that this practice exists. “My husband came to know of it only after marriage. He was very upset,” says Calcuttawala. “I just hate this thing happened to me. It is an absolute criminal act, which leaves a girl scarred for the rest of her life. It is akin to someone cutting off your toe for no reason. How dare they cut off a part of my body without my permission? Would you be OK with that?’’ Johari says some of the people she knew had to go for therapy post marriage. “They were not able to interact with their partners and the very thought of someone touching them there scared them,” she says.

At the crowded Bhendi Bazaar in Mumbai, it is easy to identify Bohri women, thanks to their colourful ridas. But there is no consensus among them on whether to continue the practice. Most older women do not question the practice; for them, it lies in the zone of unquestioning belief. Some are for the practice and ensure that even their maid’s daughters get it done; others don’t believe in the practice but lack courage to speak against it. There are mothers who haven’t got it done on their daughters, but lie about it for the fear of being ostracised.

Those who choose not to comply with the patriarchal directives have strong reasons to do so. Genital cutting can have several health implications. Eight-year-old Insia was taken to some dingy place and cut a few years ago. Her grandmother told her that she ate too many berries and thus had some growth to be removed. She could not walk for days. “There are girls who have gone through years of menstrual discomfort,” says a Bohri woman.

Rukaiya Master, 17, underwent circumcision at the age of seven. She says that every Bohri girl should undergo khatna, as it is a religious practice | Mini P. Thomas

Rukaiya Master, 17, underwent circumcision at the age of seven. She says that every Bohri girl should undergo khatna, as it is a religious practice | Mini P. Thomas

“Complications can be immediate such as shock, bleeding and infection,” says Dr Kamini Rao, gynaecologist and medical director, Milann, The Fertility Center, Bengaluru. “These can sometimes lead to death.” It can also lead to sexual dysfunction, infertility, urinary problems, vaginal tears during coitus and delivery, resulting in bleeding. “At times, bleeding can be profuse, leading to morbidity and mortality,” says Dr Laila Dave, senior consultant and obstetrician, Nova Specialty Hospitals, Mumbai. Some studies indicate that women who have undergone FGM are more likely to die during childbirth. They also have a higher risk of delivering stillborn children.

FGM victims often complain that they don’t feel attracted to men the way their peers do. “We don’t experience the same pleasure that a normal woman would during sex. The constant burning after sex does not allow me to enjoy it as a normal woman would. You cannot masturbate as your clitoris becomes extremely sensitive,” says Zainab from Mumbai, who is a marketing manager in Dubai. She says it is hard to accept that any community can go to the extent of curbing a female’s sexual desire and keeping it in control. “It is difficult to get over the fact that women in your family, who have undergone and dealt with similar situations in the past, are still willing to put their children through it, and that too well-educated women,” she says.

Johari is worried about how much effect khatna will have on her sexual life. Calcuttawala says it would have been easier for her to reach orgasm if she had not undergone khatna. “Clitoris stimulation is what makes a woman sexually excited. Khatna limits you,” says Calcuttawala, who realised how severe the impact of genital cutting can be on one’s sexual life while studying human anatomy as part of her MBBS course.

Dr Prakash Kothari, sexologist and founder-adviser to the World Association for Sexology, partly agrees with Calcuttawala. “In females, clitoris is the most reliable orgasm trigger. Most of them require additional stimulation of the clitoris to have orgasm,” he says. Kothari has examined a few FGM cases from Africa, based on which he suggests that the sexual problems FGM victims complain of could be due to psychological trauma. “It was total genital mutilation. But their desire level and orgasmic capacity were not hampered at all. The arousal sensations were very much there,” he says. “Female sexuality is dependent on the hormones produced by the ovaries, which are deep inside. Whatever you do externally will not have an impact on your desire level. I haven’t come across any particular sexual dysfunction in FGM survivors.”

In 1991, Kothari met Hanny Lightfoot Klein, who has done several studies on genital mutilation, at an international conference on orgasm. Klein had interviewed girls and women in Africa and Sudan who had undergone total genital mutilation. They had not only the clitoris but also the external vulva chopped. But their sexual responses were intact. Kothari also clarifies that if FGM is done with the purpose of subduing women’s sexual urges, it is futile. “As a medical expert, I would say it is of no help. If at all, it will only cause harm.”

The Bohra community is witnessing a silent movement against khatna. Calcuttawala has started influencing her friends against getting khatna done on their daughters. She has decided that she will never get it done on her child. “I will kill the person who suggests it be done on my daughter or any other child,” she says. Zainab says that mothers should now take a stand against khatna.

Around 15 years ago, Johari’s mother, Sophie, 56, read an article by an FGM survivor. It was an eye-opener for her. “By then, I had it done on my daughters. I told myself to let go of it,” she says. Sophie says that as far as her granddaughters are concerned, she will give the liberty to her daughters.

A Bohri activist, who goes by the name Tasleem, launched an online petition in 2011 seeking to put an end to khatna. Tasleem, who says she did not undergo khatna, forwarded her petition to the then Bohra high priest Dr Syedna Mohammed Burhanuddin. But she didn’t get any response. The petition, however, sparked off heated discussions on social networking sites. “This brutal practice has no place in a civilised world. It is not even an Islamic ritual. It is just a barbaric African misogynist ritual that found its way into a fairly progressive community,” writes Tasleem, in an email to THE WEEK.

Union Health Minister Dr Harsh Vardhan says there is a need to review genital cutting in the light of scientific thinking. “I would personally consider it as absolutely inhuman and unscientific,” he says. “Human beings are a creation of God. We should abide by nature. Whatever sensitivities we have are a part of our self. To play with or to destroy them is not justified.”

Johari knows that a legal clampdown may not help much to put an end to genital mutilation. For instance, FGM is still prevalent in the UK where it was banned in 1983. Children are still being cut every summer―the ‘cutting season’. Johari says that awareness is essential to eliminate genital cutting. For the past couple of years, she has been talking to people on a personal level. A few weeks ago, she, along with some like-minded people, formed a small informal group. “Not all of us are circumcised. We talk to as many Bohris as possible in an informal manner. We are taking a subtle approach because we don’t want the community to feel targeted or threatened. In fact, we don’t want to offend anybody,” she says.

The group, which has not been named yet, has also been trying to get an official opinion about the practice from the religious heads so that something more could be understood about it. “If the community leaders say, ‘let us not follow this practice’, it will stop overnight,” says Johari. Until then, she will speak for the little ones who are unaware of what is being taken away from them.

Some names have been changed.

.jpg) Spot of bother: A clinic where genital cutting is carried out on Dhaboo street in Mumbai.

Spot of bother: A clinic where genital cutting is carried out on Dhaboo street in Mumbai.

The mother who cared

She was known as Mama Efua, the mother of the global campaign against female genital mutilation. But Efua Dorkenoo, 65, lost the fight to cancer at a London hospital on October 18.

Originally from Ghana, Dorkenoo came to England in the 1960s, where she started working as a nurse. It was here that she met a woman in labour, who had undergone infibulation. And there began a three-decade-long fight against FGM.

In 1983, Dorkenoo founded the Foundation for Women's Health Research and Development. She has also worked with the World Health Organization and was associated with several other organisations. Her work was instrumental in the passing of the Prohibition of Female Circumcision Act, 1985, in Britain. “Of course, prevention must be central, but prosecution is the flip side of the same coin. Because in many cases if a parent or guardian feels they can get away with it, they will,” she said.

In 1994, Dorkenoo received the Order of the British Empire and came out with a book, Cutting the Rose: Female Genital Mutilation: The Practice and its Prevention. Several angry groups saw her activism as an intrusion on age-old traditions. She ignored the threats; all she cared for were the daughters with no voice.

Reconstruction options

Reconstructive surgeries for female circumcision victims are available in India.

Are they recommended for women who have had their clitoris removed? “Not really,” says Dr Archana Shah, senior consultant and gynaecologist, Sanidhya Hospital, Ahmedabad. “Clitoris can be reconstructed cosmetically, but not functionally. You cannot reconstruct the nerve endings on the clitoris, which enable you to feel pleasure during sexual activity.”

In Africa, women used to burn their vaginas in olden times so that there would be no penetration at all. “In cases where the vagina is completely burnt off or obliterated, vaginoplasty can be done, where we create the vaginal space and perform skin graft. If labia majora is disfigured, we can inject botox,” says Shah.

Living the tale: Waris Dirie | AFP

Living the tale: Waris Dirie | AFP

Gloom to bloom

Waris Dirie―the name means desert flower―was five when she was circumcised. Born into a nomadic family of camel and goat herders in a desert in Somalia, today the 49-year-old is at the forefront of the global fight against female genital mutilation. “A woman is considered dirty, oversexed and unmarriageable unless those parts―the clitoris, the labia minora and most of the labia majora―are removed. Then the wound is stitched shut, leaving only a small opening and a scar where the genitals had been,” wrote Dirie in Desert Flower, her autobiography. Typically, the circumciser is an old woman with no medical training. Besides scissors, knives and razor blades, stones are also used for cutting.

One of Dirie's older sisters bled to death following circumcision. A cousin died of an infection resulting from cutting. Dirie was circumcised by a gypsy woman, who sewed her vaginal opening with thorns from an acacia tree. There was no anaesthesia, only excruciating pain. Her mom asked her to bite on a piece of root placed between her teeth. The rock where Dirie lay was “drenched with blood as if an animal had been slaughtered there”.

Unlike her sister and cousin, Dirie survived. But life became a nightmare for her. The circumciser had left only a small hole for her to pass urine, which would take her about 10 minutes. During her periods, she wanted to die. Later, she underwent a reconstructive surgery to undo circumcision.

A well-known model, Dirie has acted in a James Bond movie―The Living Daylights. In 2002, she founded the Waris Dirie Foundation, later renamed as the Desert Flower Foundation. She was the UN special ambassador for the elimination of FGM from 1997 to 2003.