In December 2013, Avani Bansal, who had just completed her masters in law from Oxford University, landed in the district court of Harda in Madhya Pradesh. She had made up her mind to begin her career in litigation the hard way—taking up practice in criminal law in a trial court. She knew it would be tough, but that didn’t prepare her for the extremely hostile workplace.

Bansal, 28, who is about to start practice in the Supreme Court, recalls how the male lawyers in the trial court used every tactic under the belt to unnerve her—from commenting on her attire to making snide remarks about her Oxford degree to getting outright hostile by yelling at her, ‘Zyada hoshiyari na dikhao [Don’t try to act smart].’

“I was one of two or three women in a court where hundreds of lawyers practised,” she says. “I was an oddity who was stared at, humiliated, who was either an irritant for the male lawyers or a source of amusement. The lawyers were hostile, and the judges never reprimanded them.”

If Bansal, a new entrant, had to brave hostility borne out of gender bias in a trial court, a senior lawyer like Indira Jaising says she still has to tackle discrimination in the hallowed precincts of the Supreme Court. “Even after ‘I have made it’, my word is often treated as less valuable than the word of a male lawyer,” she says (see interview).

The bench appears to be no different, with women judges complaining of discrimination, too. Very few of them have made it to the top levels, and even then, their calibre is under great scrutiny. Former Supreme Court judge Gyan Sudha Misra reportedly told a fellow male judge who was constantly questioning her understanding of an issue, “Stop judging the judge, and start judging the matter.”

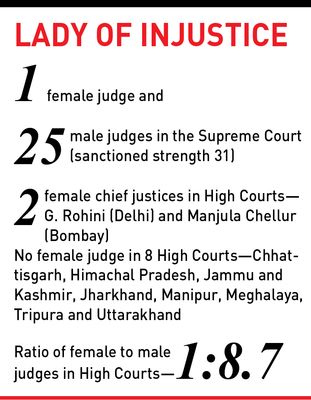

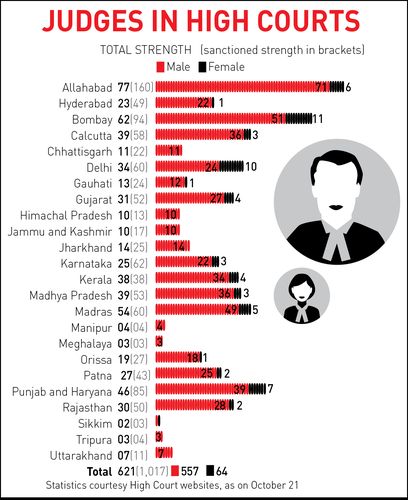

And, statistics prove it is a man’s world. There is only one woman judge—Justice R. Banumathi—in the Supreme Court as against 25 male judges. Only six women have been appointed as judges of the apex court till now. The 24 High Courts in the country have only 64 women judges compared to 557 male judges, and there is not a single woman judge in eight High Courts. While at least 44 names were recommended by the Allahabad High Court collegium to the government recently for appointment as judges, only two of them are women. It took more than four decades after independence for a woman to be appointed as a Supreme Court judge. A woman was appointed to the High Court only in 1959. At no point have there been more than two women judges in the Supreme Court.

While women got the right to practise in 1922, Jaising became the first woman additional solicitor general in 2009. The country has not had a woman solicitor general or attorney general. From 1992 to 2005, at the top three courts of the country—Supreme Court, Delhi High Court and Bombay High Court, only one woman had been designated senior advocate. The designations are on hold in the Supreme Court till it decides on a petition filed by Jaising, urging for greater transparency in the nomination of senior counsels.

Only 12 women have been designated senior counsels by the Supreme Court so far. Only eight women have got that distinction in the Delhi High Court and six in the Bombay High Court. The Allahabad High Court, one of the oldest in the country, has had only one senior woman advocate.

Women lawyers face problems right from when they enter the field. Rucha Anant Pandey, 24, who started practising at the Nagpur bench of the Bombay High Court a few months ago, says her initiation into the field was in a trial court in Pune, where she handled criminal cases along with a senior. Everyone in the court, from the bailiff to the court clerk to male lawyers asked her, “Madam, kya kar rahe ho [What are you doing here]?”, referring to her as a misfit in the world of criminal law. A judge once asked her to call her senior, and advised him to give her only certain kind of cases.

No arguments: Clients prefer their cases to be argued by male lawyers, says Supreme Court lawyer Malvika Trivedi | Aayush Goel

No arguments: Clients prefer their cases to be argued by male lawyers, says Supreme Court lawyer Malvika Trivedi | Aayush Goel

Even a seasoned lawyer like senior Supreme Court advocate Meenakshi Arora recalls how some years ago when she was arguing a matter, the judges were extremely hostile and almost threw the file. However, the same argument when made a few years later by a male senior was allowed. “Your mind has to be open. Don’t look at my gender, don’t look at my face, only look at the point that I am making,” says Arora.

There are, however, judges who are encouraging towards women. “Many years ago, a judge saw me as a well prepared young junior and there was a senior appearing against me. He gave me the full and complete right to argue the matter. That confidence has kept me in good stead for life,” says Supreme Court lawyer Malvika Trivedi.

But women are not expected to be aggressive, and if they are, they are branded as cantankerous or rude. Former Delhi High Court Chief Justice A.P. Shah recalls having once recommended a woman lawyer as a judge, but she was rejected apparently because she was ‘rude’. “If a male lawyer replies in a certain manner to a judge, it is usually taken in the stride. But if the same things were to be said by a woman, it becomes a topic of discussion for the bar or bench, and not in a pleasant way,” he says. Shah is known as one of the few High Court chief justices to recommend a good number of women for judgeship; many of the names, however, got rejected.

Women also have to deal with men who are either condescending or patronising. “Either they are nasty to you or would want to take you in their protective umbrella, which is the old boys club. They do not like women who stand on their own dint and are strong individuals,” says Supreme Court lawyer Shilpi Jain.

If you are aligned to a chamber or are related to a judge or a senior lawyer, you are a part of this club. It helps to have a godfather, says a lady judge in a district court in Delhi. She says there are many examples of women who have made it because they were either related to a judge or a senior lawyer or were affiliated to a certain chamber.

The attitude of clients is also not very encouraging. Trivedi talks about clients getting the case file prepared by a woman lawyer, but wanting their case to be argued by a male lawyer. Also, women lawyers are seen as suited to handle family law cases and social issues, and not trusted with high stake cases. Former Supreme Court judge Sujata Manohar said the inability to get cases is a main reason why women are losing out on judgeship. “Women still find it difficult to get litigation work. As a result, there are very few successful women lawyers practising at the bar. So women lawyers rarely figure among lawyers from the bar being considered for appointment as judges of the High Courts.”

Women lawyers have to be extra careful about how they dress up, too. A retired judge of the Delhi High Court is still remembered for his nasty comments on the attire of women lawyers. It is said that women were scared to appear before him because of his comments, which ranged from “Are you dressed up for a party?” to “You are so focused on your appearance that you cannot even remember to take the next date from me.”

Women judges are also at the receiving end of sexism. There have been instances of losing male lawyers foul-mouthing them. A woman judge in Karkardooma courts in Delhi filed an FIR when she was subjected to sexist abuses by a lawyer. But her own chief judicial magistrate reportedly asked her to withdraw the complaint.

Battling bias: Avani Bansal says she was humiliated by male lawyers during her stint at a trial court in Madhya Pradesh | Aayush Goel

Battling bias: Avani Bansal says she was humiliated by male lawyers during her stint at a trial court in Madhya Pradesh | Aayush Goel

A retired woman judge of the Supreme Court said there was acceptance of judgments passed by her only if they were upheld by a larger bench. Once a woman has reached the top levels in the profession, she has to work even harder to avoid any slip up. “One small mistake, and the males in the profession immediately turn around and say, ‘ye to aurat hai [she is a woman, after all]’,” says Arora.

There is also the issue of sexual harassment of women in the field, and this is said to be an important reason why women leave the profession. Jaising said she was subjected to sexual harassment in the Supreme Court two years ago. She calls the menace “the hidden dirty secret of the legal profession.” She is now fighting the case of a woman judge in Madhya Pradesh who had to resign after she made a complaint of sexual harassment against her senior.

It is ironic that the Supreme Court, which issued the Vishaka guidelines for protection of women against sexual harassment at the workplace in 1997, set up a committee to deal with complaints as required by the guidelines only in 2013.

The committee has received two complaints so far, says Prerna Kumari, general secretary of the Supreme Court Women Lawyers Association. “Action was taken in one case. The entry of the lawyer was restricted. In the other case, the complainant was not interested in pursuing the matter further,” she says.

Working conditions for women lawyers with regard to infrastructure, such as lack of proper office space and toilets, are an issue. Also, many find it difficult to balance family with the long work hours required in litigation. “I have left my children in fever to come to work. As soon as a woman lawyer cites a domestic issue, she is labelled unprofessional,” says Trivedi.

No wonder, the dropout rate of women lawyers is very high. Arora says 40 women joined practice with her in the Supreme Court; three or four years later, only four or five were left. The situation is not very different even now. Pandey says her class that passed out from the National Law University in Raipur in 2015 had girls and boys in equal proportion, but only three of the women students have taken to litigation.

A large number of women lawyers are opting for the corporate sector, joining private companies or banks and corporate law firms. And, the main reason for this is their inability to break the glass ceiling.

Justice M. Fathima Beevi, the first woman judge of the Supreme Court, says in the higher judiciary, the percentage of women judges is not very good. “It is actually just nominal…. We need to look into the reasons for that,” she says (see interview).

The standards applied to a woman when considering her for elevation are higher than those applied to a male judge, says Misra. “I would say that this happens unconsciously,” she says. “I guess lack of faith and belief in the abilities of women is still rooted in society and more so in the male psyche and we prefer to have their token presence, especially in the higher judiciary, more for the sake of symbol rather than their equal participation.”

A major reason for many deserving women not getting designated as seniors or not getting appointed to the higher judiciary is said to be their inability to lobby for those posts. “I cannot go to a party and hang out there with the guys, holding on to a drink or bringing a judge a drink,” said a lady judge in a district court in Delhi.

There are complaints about lack of transparency in designation of women as senior counsel. There is a theory in the legal circles about how former Supreme Court judge Ruma Pal was denied the chance of becoming India’s first woman chief justice simply by ensuring that she was sworn in later than a male colleague. Pal is recognised as one of the finest judges the country has had, and it is said that when she was on bench, she was the one who really wore the pants.

Manohar points out that where an examination is involved, there is a good number of women qualifying as judges. “There are more women in judicial service as the selection is by an examination and interview. Those who reach the position of district judges are considered for appointment as High Court judges. This is a slow process and any discrimination in promotion would affect a woman judicial officer adversely. This results in less women judicial officers reaching the High Court,” she says.

Ripple effect: Former Supreme Court judge Sujata Manohar says the inability to get cases is the main reason why women are losing out on judgeship | Sameer Joshi

Ripple effect: Former Supreme Court judge Sujata Manohar says the inability to get cases is the main reason why women are losing out on judgeship | Sameer Joshi

Supreme Court lawyer Sneha Kalita, who has intervened in the apex court’s hearing on the National Judicial Appointments Commission on the issue of appointment of women judges, says a proper selection procedure with transparency and accountability needs to be set up. “There are many eminent women judges and senior lady lawyers. Why should they not be chosen?” she asks.

A parliamentary standing committee on law and justice has proposed reservation for women in the higher judiciary. “The standing committee, in its report in 2015, recommended that women should have equal representation in the higher judiciary, and to ensure that, reservation could be considered,” says Dr E.M.S. Natchiappan, who is former chairman of the committee.

This has, however, evoked mixed responses. While some say it will help in increasing the critical mass of women judges, making the workspace more gender equal, there are others who say that there should be a conscious effort to give representation to women, based on their merit.

“Why should there be only one woman judge in the Supreme Court, which is supposed to have representation from all over the country? You should have women in the Supreme Court not just for projection sake but because there are women who merit to be there,” says Rekha Sharma, former judge of the Delhi High Court.

But the scenario is bound to change in a few years’ time, says Bar Council of India chairman Manan Mishra, as more and more girls are passing out of law schools. “Only recently, I was at the convocation of the National Law School in Bengaluru, and of the 11 gold medallists, eight were women,” he says.

In the 2016 Common Law Admission Test, 21,520 of 45,041 applicants were women; 23,517 of the applicants were men and four were transgenders. Of the 1,974 candidates who cleared the exam, 810 (41 per cent) were women.

Faizan Mustafa, vice chancellor, NALSAR University of Law, Hyderabad, says most law schools have 30 per cent reservation for women now. “The real issue is good female lawyers of ten years seniority who are to be considered for high court judgeship are not available,” he says. “This gap is soon going to be filled as young lawyers from lower-ranked law schools who joined practice or returned to it after corporate life of few years after payment of educational loans are going to complete 10 years soon. They are energetic, competent and assertive.”

The women in law may have changed, but will the men in law also now change?