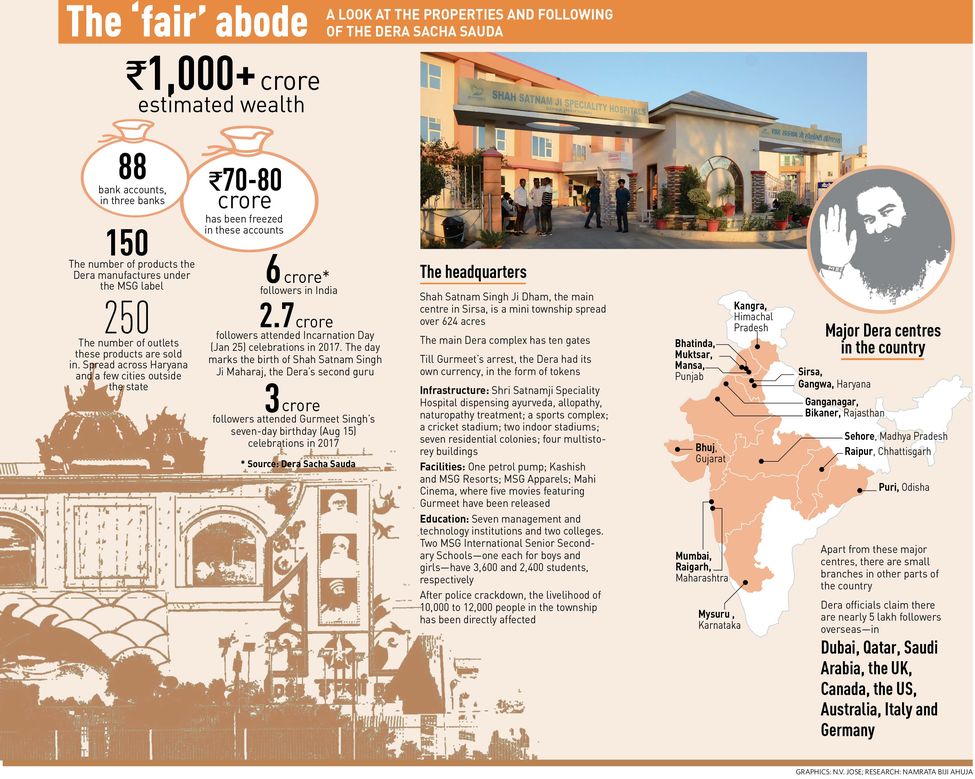

Three kilometres off Satnam Chowk at Sirsa in Haryana, and spread across 624 acres of scrubland converted into a modern township, is the headquarters of Dera Sacha Sauda, or ‘the abode of fair deal’. Founded in April 1948, the Dera describes itself as a social welfare and spiritual organisation that works towards the fairest of deals—eradicating all discrimination, fear and anxiety from the world.

Fear and anxiety, however, are rather palpable as one enters the sprawling township. The ten gates of the main Dera complex, where satsangs (religious gatherings) are held, are closed. Outside, hawk-eyed guards keep track of all movements. “Satsangs cannot happen without the baba’s presence,” says a resident. “But the gates are opened regularly for nam charcha [prayers], where old CDs of the baba are played.”

There are schools and colleges, hospitals and housing colonies, and hotels and resorts in the township. Grains, pulses and fruits are grown in nearby fields. But, what should have been a spiritual paradise now resembles a purgatory. Around 10,000 people who call the Dera home have been living in limbo ever since their beloved baba—Gurmeet Ram Rahim Singh, the Dera’s third and current master—was sent to jail on August 25 last year. A CBI court in Panchkula sentenced Gurmeet to 20 years after he was found guilty of raping two sadhvis (female disciples) in 1999.

The light literally went out of the Dera with that verdict. As more than a lakh frenzied supporters of Gurmeet unleashed violence in Panchkula, the district administration in Sirsa cut off electricity and water supply to the Dera. Even as the mob went on a rampage—burning down buildings and setting vehicles ablaze, leaving 36 people dead and 423 injured—the Army entered the township and sealed off the restricted area where Gurmeet’s residence, Tera Vas, stood.

Waiting for deliverance: A nam charcha (prayer) in progress at the Dera headquarters.

Waiting for deliverance: A nam charcha (prayer) in progress at the Dera headquarters.

Security personnel found that Tera Vas opened into a gufa, a cave-like tunnel that was exclusively used by the baba and his close associates. It was at the gufa that the sadhvis were attacked. In 2002, one of them wrote to prime minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee that Gurmeet had summoned her to the spot, where she found him watching porn. On a bed nearby, she saw, lay a revolver.

In her letter, the hapless sadhvi said Gurmeet repeatedly assaulted around 40 girls belonging to families that were fanatically loyal to him. The sadhvi herself was summoned every three months. The letter later became the basis of the CBI investigation against the controversial godman.

For the faithful, Gurmeet’s fall was as shocking as it was ironical. He had been called, among other things, the greatest engineer—“one who undertakes character building” for the sake of his disciples, says the Dera website, teaching them “to spend a life full of values, principles and righteous action”. He was the Dera’s guruji and pitaji, the wise teacher and revered father who could do no wrong.

“People used to ask pitaji: When the spark in a relationship between a man and woman starts fading, what should we do?” recalls a Dera official. “He used to tell them that the connection has to be from one soul to another. Until that is achieved, no amount of physical pleasure can recharge a relationship. This is why he called himself the Love Charger. He was the medium between the masses and the one and only charger, which is God himself.”

Students outside the Dera’s senior secondary school for girls.

Students outside the Dera’s senior secondary school for girls.

His followers may tend to refer to Gurmeet in the past tense, but they outwardly root for his comeback. There is good reason: After taking charge of the Dera in September 1990, he transformed the “spiritual wealth” bestowed on him by his predecessor, Shah Satnam Singh Ji Maharaj, to a worldly empire worth hundreds of crores of rupees. Factories owned by the Dera manufacture as many as 150 products labelled MSG (short for ‘messenger of God’, one of Gurmeet’s epithets). The products include maida, sugar, pulses, biscuits and juices, and they are sold through 250 outlets across Haryana and a few other cities outside the state. Aloeji, a Frooti-like soft drink with aloe vera in it, is especially popular among children in the region.

Today, however, the musty smell of aloe vera decaying in the fields reveals how badly the Dera’s businesses have been hit. “My factories are shut and all the raw material worth several crores is rotting in godowns,” says Ram Lakhaya Agarwal, alias Bittu Singh, who is now virtually in charge of the Dera’s production wing. “The livelihood of nearly one lakh people here has been affected. The factory workers are jobless. Even property rates have gone down. What sin have I done to deserve this?”

Bittu says there was huge demand for Dera-made food products during satsangs in Sirsa and neighbouring towns. “It was a brand, and a big hit among people, as these were natural products,” he says. According to him, thousands of outsiders, too, depended on the Dera for their livelihood.

But the Dera is now losing its wealth and the trust of the people. “I have not stepped out of my house for several days,” says Bittu, who lives in one of 30 bungalows at the Dera’s Shah Satnamji Colony. “If we go anywhere, people look at us with suspicion.”

Shri Satnamji Speciality Hospital, which provides low-cost diagnosis and treatment to inmates and outsiders, has fallen on hard times | Aayush Goel

Shri Satnamji Speciality Hospital, which provides low-cost diagnosis and treatment to inmates and outsiders, has fallen on hard times | Aayush Goel

Gurmeet’s charisma and philanthropy had for long helped him hide the dark underbelly of Dera Sacha Sauda. He gave food to the hungry, homes to the homeless and promises of a better life to orphans, social outcasts and sex workers. In a region where caste equations loomed large, Gurmeet portrayed himself as a saviour who wanted to establish a compassionate, egalitarian society. Not surprisingly, dalits and people of other backward communities in Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Delhi, Punjab and Haryana became the mainstay of the Dera, giving it considerable political clout as well.

His fanatical followers helped Gurmeet establish himself as a spiritual brand. At Sirsa, the Dera has some 30 retail outlets, a shopping mall and a movie theatre. All are closed now. Outside Mahi Cinema, the movie theatre, a poster shows Gurmeet in Jattu Engineer, which was released months before he went to jail. MSG resorts and hotels, with their tacky structures modelled after the Eiffel Tower and the Taj Mahal, have also put up the shutters for want of tourists.

Flanking the main street in the township are shops named Sach General Store, Sach Drycleaners, Sach Dairy Chai, Sach Hair Saloon and Sach Footwear. They are open, but struggling to stay afloat. When Gurmeet was in charge, the Dera had its own currency in the form of tokens valued up to 0500. Once the only currency used inside the complex, they are no longer available.

In a hushed tone, Bittu says the stigma attached to the Dera is now so huge that its inmates are unable to find matches for their children. “Earlier, families [outside] used to be eager to get a boy or girl from a Dera family,” he says. “It was a given that they don’t drink or eat meat, and that they live a pure life. But now, we are looked at suspiciously.”

Lives in limbo: Women cooking food at the community kitchen at the Dera.

Lives in limbo: Women cooking food at the community kitchen at the Dera.

Bittu’s brother says his own in-laws view him with suspicion. “When I visited my wife’s family recently, they were reluctant to host me overnight,” he says. “They ask whether there is any truth in the allegations of wrongdoings in the Dera. Since I lived there, they feel, I would surely know what used to happen there. No one believes me. They say if the police get to know that there is a Dera premi [follower] in their house, they may come knocking, and so we should go back to the Dera.”

The women in Bittu and his brother’s bungalow busy themselves in the kitchen as their children drive battery-powered toy cars in the extended driveway. “It is all pitaji’s blessing that we have reached here today,” says Bittu’s wife. “We come from a humble background in Punjab, where we used to run a grocery store. But pitaji blessed us and gave us everything.”

Not all have been so fortunate. When Gurmeet was convicted, 13-year-old Pawan and 12 other boys were bundled out of the Dera to the district child protection centre (CPC). The authorities feared that Dera supporters would use orphans like him as human shields if clashes broke out with security forces. Pawan’s sister, 14-year-old Saugatha, was part of the group of nineteen shahi betiya (royal daughters) adopted by the Dera.

The children had been ‘donated’ to the Dera by their families, and were living in its confines for years before CPC rescued them. All except two orphans in the group have now been sent to their relatives. CPC has got in touch with the Delhi-based Central Adoption Resource Authority, a statutory body under the Union ministry of women and child development, to make the two children legally eligible for adoption.

Mahi Cinema, which is closed now | Aayush Goel

Mahi Cinema, which is closed now | Aayush Goel

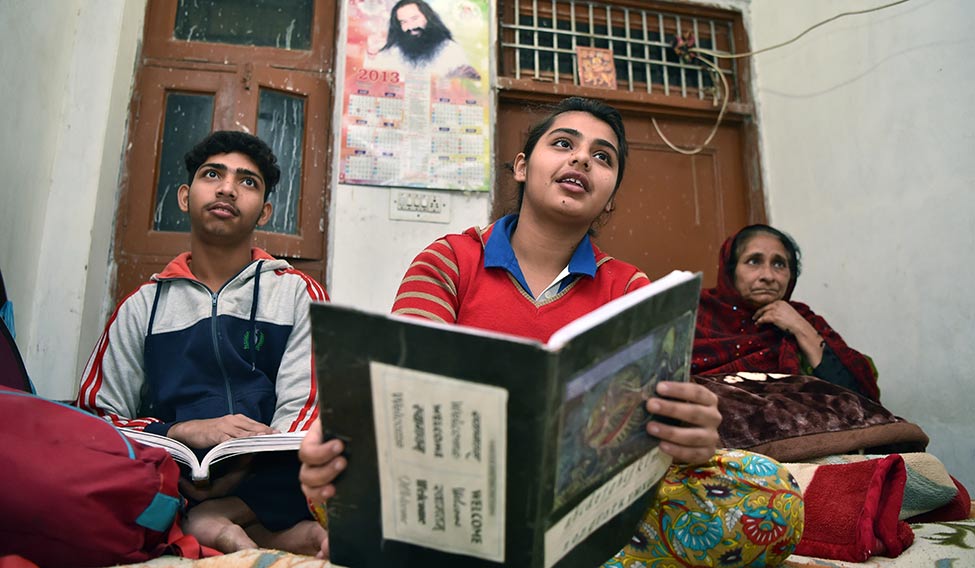

Pawan and Saugatha now live with their grandmother Neelam, though they continue to study at the English-medium, senior secondary schools run by the Dera. The three live in a small room on the third floor of a shabby building on a tiny, crowded lane in Sirsa. Sitting on a single bed, they struggle to keep themselves warm in the winter.

Neelam had brought the children to the Dera from Saharanpur in Uttar Pradesh in 2006. It wasn’t faith, but necessity that prompted her to do so. The children had lost both their parents, and there was no way she could take care of them. “Their mother died after she suffered an intense stomach ache, and the father was an alcoholic,” says Neelam. “I kept the children with me, but I wasn’t earning much. I was told that the government schemes for orphans will benefit these children, but no help came our way. I was running around in circles when someone told me that we could take shelter in the Dera.”

Neelam, 65, is a diabetic and a heart patient, and she often coughs as she speaks. “I get Rs 2,000 as pension, but that is not enough to run a house and bring up these two children. We are living a life of uncertainty, as the Dera may not allow them to continue their free education since they are no longer living there.”

At the Dera, she says, all their needs were met. “Their food, uniform, books—everything was taken care of. Nothing wrong ever happened with them. In fact, Pawan is a swimming champion today,” says Neelam.

Worried, frustrated: Saugatha (centre) with her brother Pawan and their grandmother Neelam. The siblings were rescued from the Dera, but they now want to return | Aayush Goel

Worried, frustrated: Saugatha (centre) with her brother Pawan and their grandmother Neelam. The siblings were rescued from the Dera, but they now want to return | Aayush Goel

Gurmeet loved sports, especially cricket. Apart from promoting traditional games like kabaddi at the mini khel gaon in the Dera complex, he also invented games by fusing western and Indian sports. The result were games like gul stick, a mix of gilli danda and hockey.

Apparently, Gurmeet’s interest in sports is what led him to produce movies. The story goes that he once waited to play cricket with his followers, but none of them turned up. When he later asked them why they had not come, they said they had gone to watch a movie. A good listener, Gurmeet asked his followers what kind of movies they liked. They said they would love to watch films that not only entertained them, but taught them values as well. It led Gurmeet’s foray into filmmaking.

Both Pawan and Saugatha want to go back to their former lives. “We want to continue our studies at the Dera. The teachers are very good and we have all facilities. It’s the best school in Sirsa,” says Saugatha, proudly breaking into English.

The boys’ school has around 3,600 students; the girls’ school has 2,400. The Dera also runs four colleges, where thousands of students pursue graduate and postgraduate courses.

When asked about one thing they have learnt from Gurmeet that they feel they cannot learn anywhere else, Pawan says, “It is insaniyat [humanity].” Gurmeet’s followers suffix the word ‘insan’, or human, to their names.

“The orphanage was started by the Dera several years ago,” says Dr Gurpreet Kaur, the district child protection officer who rescued Pawan and other children. “I must admit that the Dera took good care of the children who were virtually abandoned by their loved ones. The only issue was that they did not care for rules and regulations. Once inside the Dera, these children were not even allowed to meet their families.” (In its defence, the Dera says constant interference by family members made the children feel “emotionally torn”.)

With the help of security forces, and wearing a protective jacket and helmet, Gurpreet rescued the children in the dead of night soon after violence broke out after Gurmeet’s conviction. She says the children had to undergo multiple counselling sessions before they could reunite with their families.

“The bitter truth is that it is the second time that these children have lost their families,” says Gurpreet. “Though we are not Dera followers, we sang bhajans with them, and talked about their faith after the violence broke out…. We had to do all this because they were worried for their pitaji.”

Their sense of loss, perhaps, comes from the feeling that they are losing access to a better life. The Dera has long provided its supporters with facilities they could not get anywhere else. Shri Satnamji Speciality Hospital run by the Dera has been providing low-cost diagnosis and treatment to thousands of patients every year. The hospital has its own eye and blood banks, and has experienced doctors on its payroll. “This was all barren land. It is baba’s single-handed effort and perseverance that converted this sandy area into one that houses world-class institutions,” says Dr Puneet Maheshwari, consultant anaesthetist who had studied at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences.

Since Gurmeet’s conviction, however, the hospital has seen a fall in the number of out-patients—from nearly 500 a day to 150. “While 200 children used to come for [thalassaemia] treatment on an average during a week, the number has now been reduced to 75,” says Vinod, the blood bank’s technical supervisor.

Sanjeev Kumar, a biomedical engineer, started working at the hospital in 2014. He used to earn Rs 40,000 a month and was provided free accommodation. The top doctors, he says, earned up to Rs 2.5 lakh. The salaries, however, have not been paid for months now, something Kumar says has never happened in the past. The staff strength has come down from more than 250 employees to nearly 150.

“After all the bank accounts of the Dera were frozen, we have not got our salaries. But we are not complaining. Baba is innocent and he will make a comeback. Till then, we are ready to serve the Dera,” he says, but not very convincingly.

The police say the Dera had several crore rupees in its 88 accounts in three banks. The money, they say, was used to fund the riots in Panchkula and elsewhere after Gurmeet was found guilty.

Jasmeet Insan

Jasmeet Insan

The riots, and the ensuing cases against its supporters, now haunt the Dera. The footfalls are fewer, and the Dera knows that it badly needs an image makeover. Preparations for that are going on discreetly. Dera officials say celebrations are being planned for January 25, the Incarnation Day of Gurmeet’s predecessor Shah Satnam Singh Ji Maharaj. Last year, they claimed, more than 27 million people had come to seek Gurmeet’s blessings on the occasion.

In his absence, though, the expectations this year are modest. The Dera knows that it is time to go back to the basics. No less than a divine intervention could save it from falling apart.

Jasmeet Insan, Gurmeet Ram Rahim Singh’s son

“I don’t aspire to be guru in the absence of my father. I don’t want the gaddi [seat of power]. My father will always remain the guru. I am sure guruji will get justice from the higher courts and soon be among us. He is honest and innocent and has relentlessly been working for the welfare of the masses. I can never think of taking his seat. The management of the Dera Sacha Sauda and the people associated with it will continue to work on the directions given by guruji and serve the people.”