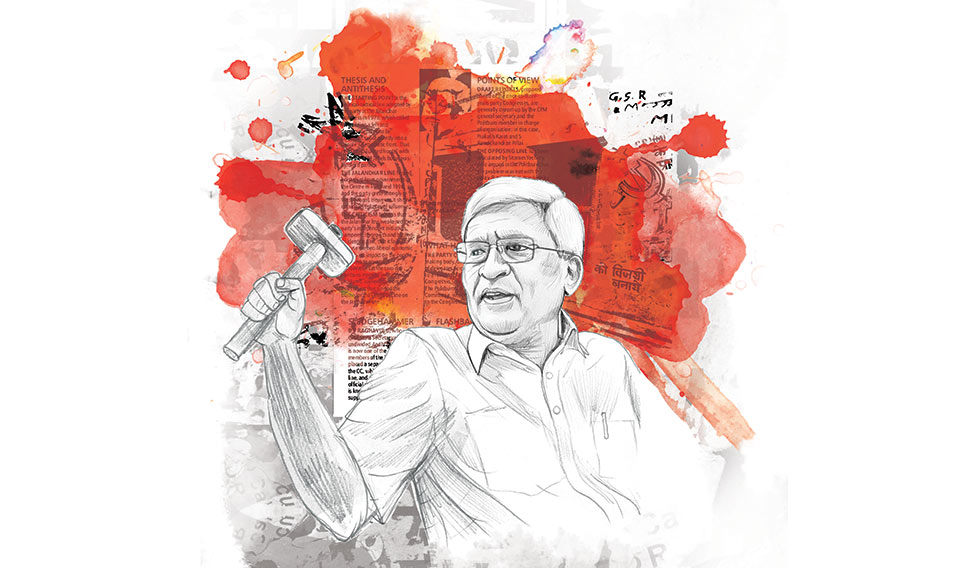

On July 9, 2008, Prakash Karat took the biggest gamble of his political life. And, like most gamblers do, the CPI(M) general secretary believed that his wasn’t a gamble at all, but a decision that hinged on reason and conviction.

The gamble entailed sending a letter to the Rashtrapati Bhavan, informing the president of the decision of the Left parties to withdraw support to the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance government. The letter had two clear-cut objectives. One was to prevent the UPA government from submitting a safeguards agreement to the board of the International Atomic Energy Agency in Vienna. If ratified, the agreement would pave the way for a civil nuclear deal between India and the US, which Karat did not want.

The other objective was to pull the rug from under the government. The UPA had just 234 members in the Lok Sabha, 38 short of majority. If the Left’s 59 MPs withdrew support, the government would have to prove majority in Parliament. Karat sensed that the nuclear deal would automatically fall through if the government fell.

The letter was intended to be timed well. It would reach the Rashtrapati Bhavan on July 9, when the government planned to submit the agreement to the IAEA board. Around noon that day, Karat met external affairs minister Pranab Mukherjee, who had been parleying with him. Mukherjee had earlier sought the intervention of CPI(M) veteran Jyoti Basu, who was apparently convinced of the merit of the nuclear deal.

“Basu spoke to Prakash Karat and suggested that there might be value in Karat meeting me,” Mukherjee would later write in The Coalition Years, the third volume of his autobiography. “Karat did meet me, but remained vehement in his opposition, and maintained that the Left would join hands with the BJP to vote the UPA out.”

That day, as Karat read out his letter, Mukherjee prepared for the inevitable. A Left delegation led by Karat then went to the Rashtrapati Bhavan. “In view of the withdrawal of support by the Left parties to the Manmohan Singh government, we request you to direct the prime minister to seek a vote of confidence in the Lok Sabha immediately,” the letter demanded of the president.

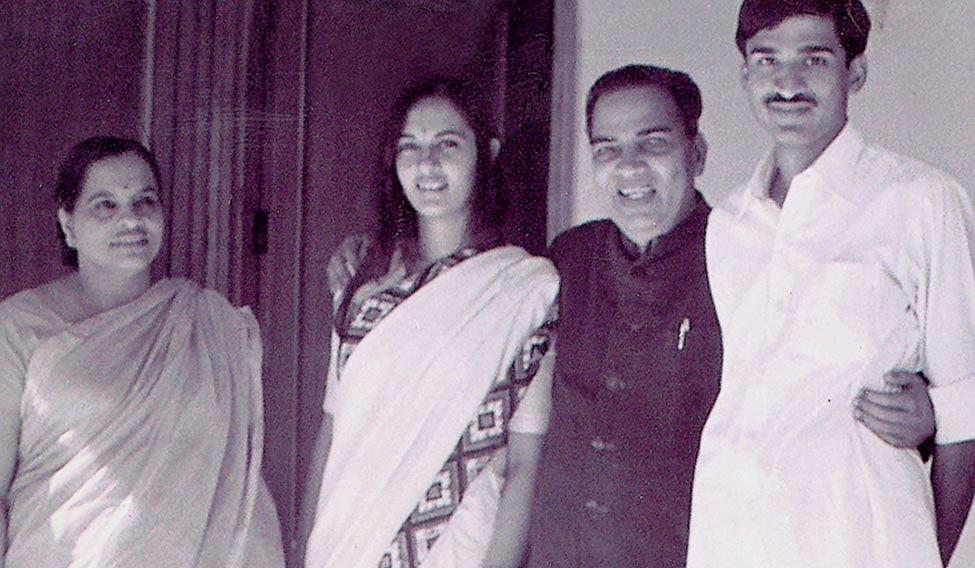

The future Marxist: Karat with his father, Padmanabhan Nair, and mother, Radhamma.

The future Marxist: Karat with his father, Padmanabhan Nair, and mother, Radhamma.

It was around 12.30pm in India, and 8am in Vienna. As Mukherjee perhaps knew, Karat’s gamble was doomed to fail because of the time difference. The government got a window to decide on whether to risk losing its face by filing the safeguards agreement. Calls were made, favours were exchanged and, within hours, another letter reached the Rashtrapati Bhavan. As the agreement was being filed in Vienna, the Samajwadi Party informed the president that it was pledging the support of its 39 MPs to the UPA.

That day, Karat and the Left found themselves out in the cold.

He had discounted far too many variables. For one, the fall of the government would have meant early elections, but nobody had the stomach to fight them. The economy was entering troubled waters—inflation was high, interest rates were low, and the mortgage bubble in the US was about to burst. Everyone knew that snap polls would benefit only the BJP.

Two, the agreement would have hardly clinched the nuclear deal. It was just one of several obstacles that India had to overcome before the deal could be inked. As others saw it, there was still room for manoeuvres and compromises. Three, and perhaps most importantly, Manmohan Singh and Mukherjee enjoyed more goodwill in Parliament than the doctrinaire Karat did.

The way Karat’s plan collapsed over the following weeks was rather symbolic. On July 22, the UPA won the trust vote by 275 votes against 256. Speaker Somnath Chatterjee, who belonged to the CPI(M), decided not to follow the party’s orders to vote against the government. He was summarily expelled from the party the following day. Nine days later, the IAEA approved the agreement.

The same day, the CPI(M) suffered an unexpected loss. Harkishan Singh Surjeet, one of its founding members, died at a hospital in Noida. As the party’s general secretary before Karat, the affable Punjabi was renowned for his ability to build bridges across the political spectrum. He had been instrumental in stitching up several coalitions, including the UPA.

When Surjeet passed the mantle to Karat in 2005, the CPI(M) was in its strongest position in decades. It was in power in three states, had 43 members in the Lok Sabha, and led a Left coalition that could dictate terms to the Union government.

On August 1, as he passed away, the CPI(M) began a long, bitter period of decline. In 2015, when Karat finally stepped down as general secretary after three consecutive terms, his party was in power in just one tiny state, and the number of MPs had dwindled to just nine.

From Madras to Edinburgh

Power couples: A.K. Gopalan (second from right) and his wife, Susheela Gopalan (extreme left), with Brinda and Prakash Karat.

Power couples: A.K. Gopalan (second from right) and his wife, Susheela Gopalan (extreme left), with Brinda and Prakash Karat.

By all accounts, Madras of the swinging sixties was a happening place. Like other big Indian cities of that time, it was a place where the traditional married the modern, giving birth to a generation of rebellious, affluent young people with long hair, short sleeves and awkwardly large collars.

Prof J. Vasanthan, the renowned theatre artiste who began his career at the Madras Christian College (MCC) in the early sixties, once fondly remembered a tall youngster who turned up near his window wearing a long coat on a rainy night. “Harry Palmer,” whispered the young man. “Harry Palmer here!”

He was Vasanthan’s favourite student. Days earlier, he and Vasanthan had gone to watch The Ipcress File, starring the British actor Michael Caine as a secret agent called Harry Palmer. “Both of us liked Caine, who was always in a long overcoat in this series of films,” Vasanthan wrote decades later, recalling his bond with Karat. That night, when Karat turned up as Palmer, the rain didn’t stop them from going to the movies again.

Karat was born on February 7, 1948, in Letpadan, where his father, Chundoli Padmanabhan Nair, was employed as a clerk at Burma Railways, and later at Burma Oil Pipeline Project. He lost his sister there to a sudden illness, and his father when he was 13. By then, he had spent years dividing his time between Burma and his hometown in Palakkad in Kerala.

Karat’s mother, Elapully Karat Radhamma, wanted him to study in Madras. “After my father’s death, my mother became an LIC agent,” Karat said in an interview to the Malayala Manorama in 2008, when he turned 60. “She took a loan, built a house in Madras and gave it out on rent. We used to live in the outhouse, off the rent.”

According to Vasanthan, Radhamma brought up his son “with a single-minded vision of making him a successful and happy human being”. When Karat was a second-year undergraduate, she yielded to his demand for a Jawa motorcycle. “He insisted on giving me a ride,” Vasanthan later recalled, “and I held on for dear life as he plied his vehicle with youthful exuberance.”

He had first sought out Karat when the latter won an all-India essay contest sponsored by The Hindu and a Japanese company in 1964. The essay got Karat a chance to see the Tokyo Olympics. “When he came back, he held forth on his trip, and the splendours of Japan and the thrills of the sports meet he had gone to witness,” the professor wrote.

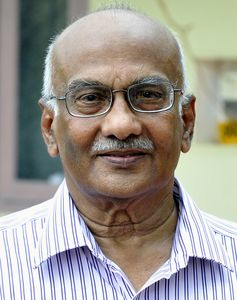

Different shades of red: Yechury (extreme right) resembles the affable Surjeet (centre), while Karat (extreme left) has inherited the ideological rigidity of Sundarayya, the CPI(M)’s founding general secretary | Getty Images

Different shades of red: Yechury (extreme right) resembles the affable Surjeet (centre), while Karat (extreme left) has inherited the ideological rigidity of Sundarayya, the CPI(M)’s founding general secretary | Getty Images

For the Japanese, the sixties weren’t just swinging, they were ‘golden’. Thanks to big corporations, unionised workforce and US interventions to prevent the Japanese from taking to communism, Japan was witnessing an economic miracle. By the end of the 1960s, the once war-torn country became the world’s second largest economy. Karat was impressed.

After graduating from MCC, he won a scholarship to study in Edinburgh. He sold his beloved Jawa and some shares in his name, besides borrowing Rs 10,000 from a trust, free of interest.

To Karat, Edinburgh mirrored what the writer Alexander McCall Smith wrote about it: “A city of shifting light, of changing skies, of sudden vistas”. He met Victor G. Kiernan, a distinguished professor of history and an Indophile, who, in Karat’s own words, “embedded” Marxism in him.

Kiernan had lived in India between 1938 and 1946, witnessing the birth of communism in the country. He had predicted that the challenge for the Indian Left would be to find creative solutions to the caste system and economic disparities.

Karat once recalled how he first met Kiernan, who began by asking which part of India he came from: “Next, he asked my caste, which I never use. When I mumbled ‘Menon’, he joked: ‘So you’ll go into the civil service as all Menons do.’ I said there were two kinds of Menons—ones who became civil servants and the others who became communists. I was the latter type. We both had a good laugh.”

Interestingly, Karat ossified into a communist at a most unlikely place and era. Edinburgh of the late sixties was psychedelic—aristocracy was on the wane, commoners were mostly happy, seats in universities were doubled while fees were halved, and the newly-formed ‘beat bands’ were vying for fame, money and drugs.

Karat, apparently, never quit the library. “I used to work hard, six hours in the library, three-four hours for lectures, etc,” he said in the 2008 interview.

He returned to India in July 1970, determined to join the CPI(M). “When he came back, he was a changed person,” wrote Vasanthan. “He kept talking about Marxism, trying to convince me of its importance. He also told me that he was a party member now. I didn’t much care for this new development, and I am afraid I told him so rather harshly. I felt that all his mother’s dreams for his success might come to naught.”

A door and a window

G. Kiernan

G. Kiernan

Vasanthan’s fears were misplaced. Karat was destined to rise swiftly, mainly because he had knocked on the right door. When he returned from Edinburgh as a full-blooded Marxist, he went straight to the CPI(M) top brass. He was asked whether he would be interested in going to Delhi and work with A.K. Gopalan. Comrade AKG was then leading the CPI(M) in Parliament.

“I jumped at the opportunity,” said Karat in the 2008 interview. “But I had to give a reason to my mother for leaving. So I applied to Jawaharlal Nehru University and got a scholarship to study there.”

P. Sundarayya, then CPI(M) general secretary, also took Karat under his wings. In Karat’s words, Sundarayya “decided” that he should contest elections at JNU. Karat cofounded the Students Federation of India there, became its second national president, and the third president of the JNU Students’ Union. During the Emergency, he was arrested twice and spent a week in jail.

In those dark years, Karat was held captive in other, more delightful ways. While staying in a cramped room full of books in the SFI headquarters in Calcutta, he took to gazing out of a window that opened to the office of People’s Democracy, the party organ. He met a girl called Rita there, a rebellious spirit who had been educated at Welham in Dehradun and Miranda House in Delhi. She wanted to return to Delhi, which the party allowed after a while.

Karat came to know Rita better after she relocated. They decided to get married, but both of them wanted the Emergency to be over first. Surjeet and Sundarayya, who knew the couple well, advised against waiting, and fixed the wedding.

“For a long time, nobody in Delhi knew her as Brinda,” Karat recalled in 2008. “Till the 1980s, she was known as Rita in public.” Karat, too, had an alias—Sudheer. When the Emergency ended, Rita and Sudheer were man and wife.

The rising theoretician

On August 19, 1948, the legendary P. Krishna Pillai died of a snake bite. As Kerala’s first communist, he had organised several mass struggles through the preceding two decades. Before he died, he scribbled one final note to his followers. “Forward, comrades!” read the note’s last line.

For several years, Pillai’s comrades persevered on, unmindful of their big handicap: When proposing his theory, Marx had only taken into consideration the realities of Western Europe, which was largely industrial than feudal. Kerala, and the rest of India, had been the other way around. And, there were evils of the caste system to boot, which Marx had largely been unaware of.

The communists who came after Pillai faced a conundrum: In the absence of an industrialised society, they could not define ‘class’, in the true Marxist sense of the word. As decades passed, the caste-class contradictions became increasingly hard to ignore. There was a “lack of theory”, as Kiernan had bemoaned in the case of early Indian communists.

By the sixties, though, a number of Indian theorists were successfully applying Marxist principles in history, sociology and even electoral politics. The tallest such theoretician in the latter category was the diminutive E.M.S. Namboodiripad, who had twice become chief minister by the time Karat joined the CPI(M).

“The Kerala communist movement was fortunate in having P. Krishna Pillai, the founder and master-organiser; A.K. Gopalan, the mass leader; and EMS,” Karat wrote in a tribute after Namboodiripad died in March 1998. “In the annals of the movement, history will record the preeminent position of EMS in this brilliant trio, who fused his immense theoretical abilities with unerring practical politics.”

Karat had, by then, completed six years as member of the Polit Bureau, the highest decision-making body of the CPI(M). His rise to the PB had been swift: it had taken just 22 years. S. Ramachandran Pillai, a peasants’ union leader, had worked for a long 46 years to join the PB the same year as Karat did.

Karat joined the PB in January 1992, a watershed year for his party. The dissolution of the Soviet Union the previous month had dealt a crushing blow to communists across the world. The CPI(M), which had considered the Soviet Union as a torchbearer of the revolution, was now struggling to find direction.

In many countries, communists responded to the fall of the Soviet dream by transforming themselves into ‘social democrats’. The SocDems espoused a lamer version of communism—they resigned themselves to fighting for justice within the framework of a capitalist economy.

Karat, however, would have none of that madness. At the party congress in Madras that year, he helped draft a resolution that termed SocDems as traitors who had betrayed the working class. In verbose, barely comprehensible prose, the resolution spelt out the CPI(M)’s path. “The CPI(M),” said the concluding paragraph, “taking into account the evolution of the socio-economic systems of both contemporary capitalism and socialism, considered both at the world level as well as in each country, is committed to carry[ing] out a deeper analysis which has been hindered, as pointed out above, by revisionism and dogmatism in the international communist movement which, in turn, led to theoretical stagnation to a certain extent.”

In plain English, it said the comrades were unsure what hit them, and were committed to finding that out. That January, Karat became a member of not just the Polit Bureau, but the editorial board of the party’s academic journal, The Marxist, as well.

The soft-spoken dictator

Ramachandran Pillai

Ramachandran Pillai

In July 1903, when he was just a minor player in Russian politics, Lenin scored a significant tactical victory. That year, the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party met in Brussels and London for its second congress. Lenin’s persuasive skills made him a star, but many of his proposals were defeated by ballot. As the party split into two factions, Lenin shrewdly named his group the Bolsheviks, which in Russian meant ‘in the majority’. Lenin’s group was actually in the minority, but since he had already claimed a name for his group, the majority automatically became Mensheviks, or ‘in the minority’.

Lenin later coined the term ‘democratic centralism’, which enshrined majoritarianism within the party. “The principle of democratic centralism… rules out all criticism which disrupts the unity of an action decided on by the party,” Lenin wrote in 1906. That definition later became the bedrock of the CPI(M)’s organisational structure.

The soft-spoken Karat is so firm a believer in democratic centralism, that many of his party colleagues accuse him of being dictatorial. Within the CPI(M), a strong critic of Karat’s love for centralism is the economist Prabhat Patnaik. “Free scientific discussion is like oxygen for a revolutionary party; without such discussion it cannot survive,” he critiqued in 2007. “But such free discussion requires not just complete intellectual freedom, but also the existence of a multiplicity of opinions….”

Writing in The Marxist in 2010, Karat dismissed Patnaik’s view, saying there could be free debates within the framework of democratic centralism. His critics, however, maintain that Karat has been using the system to stamp out differences of opinion.

A case in point is Karat’s terse dismissal of a draft political-tactical line that was to be discussed at the Polit Bureau meeting in early December. The draft was prepared by Sitaram Yechury, who succeeded Karat as the party’s general secretary in 2015. Yechury wants the CPI(M) to tie up with secular parties to fight the BJP in the next Lok Sabha polls. The draft reflected his view, which Karat found abhorrent. Apparently, one member of the Karat camp responded to Yechury’s draft saying, “The CPI(M) is not prepared to commit suicide.”

The tussle between Karat and Yechury is legendary. Unlike Karat, who was his senior at JNU, Yechury is a genial man who loves the good life. “Karat has inherited the ideological rigidity that Sundarayya had,” said a former member of the party’s state committee in Kerala. “Sundarayya, too, was opposed to joining hands with the Congress during his time. Yechury, on the other hand, is more like Surjeet. In Delhi, even rivals call him by his first name.”

Karat had reportedly tried to prevent Yechury from being appointed as general secretary in the 2015 congress. He apparently wanted Ramachandran Pillai to succeed him. A furious Yechury is said to have skipped several meetings to convey that Karat’s move wouldn’t go unopposed. Yechury is even said to have told a reporter that “sahib, biwi aur ghulam [master, missus and slave]” were trying to block him, referring to the troika that includes Pillai and Brinda Karat.

The fact is, Karat remains dominant even now. He has the support of 10 of 16 Polit Bureau members, and a majority of the members of the central committee, which is just under the PB in the party’s pecking order. It means that Yechury’s dreams of following in Surjeet’s footsteps, and of stitching up a ‘secular coalition’ that includes the Congress, will not be realised soon.

It seems Karat’s hostility to the Congress was aggravated by his failed gamble in 2008. Months before the 2014 Lok Sabha elections, when the BJP was in the ascendant, Karat declared that the Left would work to defeat the UPA. “The UPA and the Congress should be defeated,” he said. “We are not going to work for their return.”

As the 2019 elections approach, Karat is not wavering. He says the fight against the BJP cannot be conducted in alliance with the Congress, which he terms as “a bourgeois party governed by the ruling classes”.

“Last year, he wrote an article saying the BJP government was not fascist, but merely authoritarian,” said a senior leader of the Communist Party of India, the CPI(M)’s junior ally in the Left coalition. “The real objective of that article was not to define the current political situation in India, but to preempt any talk of joining hands with the Congress. For, in the event that the CPI(M) comes to the conclusion that the government is indeed fascist, it would need to work towards forging a secular alliance against the BJP.”

What is interesting, according to the CPI leader, is that the CPI(M)-led Left government in Kerala is fighting the BJP by openly terming it fascist. Some observers say the CPI(M) is trying to make inroads into the Congress’s minority base by positioning itself as the only alternative to hindutva politics.

By refusing to ally with the Congress at the national level, though, the CPI(M) is helping the BJP. A few months ago, the Karat camp was instrumental in denying Yechury a third term in the Rajya Sabha. The reason cited were the party regulations that prohibited leaders from serving more than two terms in the upper house, and the fact that Yechury would have to seek the support of the Congress in Bengal for his victory.

The decision so infuriated Gautam Deb, the party’s central committee member and former West Bengal minister, that he called it “an insult to the people of Bengal”. “I call this cutting your nose to spite your face,” wrote the columnist Karan Thapar. “This [Yechury being denied another term] is a gift to the BJP and it brings the prime minister a critical step closer to his goal of an opposition-mukt Bharat.”

Deb’s angry response earned him a reprimand from the central committee. The party asked him to file an explanation, and Deb gave a detailed reply. When asked about what he wrote, Deb told THE WEEK: “Let’s not make the situation more complicated for me. I told the party whatever I had to say.”

A central committee member in Delhi said Deb’s explanation so angered the Karat camp that some of the leaders wanted him to be expelled. A section of leaders from Burdwan also opposed Deb, as he was perceived to have grown close to the Congress.

Perhaps, the trouble with Karat is that he knows his strengths as a theoretician, but is oblivious to the rough and tumble of electoral politics. Yechury indicated as much in 2008, when, in a glowing tribute to Surjeet, he recounted a story from the 1930s. Surjeet, at that time, was at a concentration camp with fellow communist legends. One day, to keep themselves amused, he made a bet: that he could consume a ser of ghee in one go.

A ser is about one litre, so the other leaders thought he was just joking. Nevertheless, they smuggled in the ghee, and Surjeet consumed it in one go. He won, but now others began to fear for his life. They sat awake through the night, ready to assist him in case something happened.

Nothing, apparently, happened. “Surjeet woke up in the morning,” wrote Yechury, “and with his lota went into the khet [field] and returned to tell his comrades, that ‘Urban communists will have to work very hard to understand the real India’.”

With his ideological exertions, it seems, the urbane Karat is working rather too hard.

WITH JOMY THOMAS & RABI BANERJEE