On June 30, 1959, six months after his comrades came to power in Havana, Ernesto “Che” Guevara landed at Delhi’s Palam airport. Protocol-wise, he was a ‘lightweight’—Che had no official role in the Fidel Castro government at that time, and communiqués described him rather vaguely as a “national leader of Cuba”. So, his entourage of six was received by a lone, mid-level Indian bureaucrat.

The following day, Che met Jawaharlal Nehru, gifted him a box of cigars, and got an ornate khukri in return. After spending four days in Delhi, he went to Lucknow and Calcutta. The communists in Bengal ignored him, but the Congressmen didn’t. Chief Minister B.C. Roy—who, like Che, was a medical doctor—is said to have warmly welcomed the left’s future mascot. (Much of what we know today of Che’s historic visit was unearthed by journalist Om Thanvi in his 2007 trip to Cuba.)

Back in Havana, an impressed Che filed a report to Castro, describing India as, among other things, a potential market for Cuban commodities. “Among the products that we can export,” he wrote, “could be copper, cocoa, rayon fibres for tyres and, perhaps in the near future, our sugar.”

Indians, however, ended up importing Che himself, and the spirit of rebellion he symbolised. Five decades after his death, the Argentine revolutionary is a leading figure in the communist pantheon in India, and his face has come to represent a wide array of causes—from campus protests to farmer rallies, and solidarity marches to the hipster ethos.

“Che’s life and his role in reshaping Cuba are a lesson in how to bring about a creative revolution, even in a land as different from Cuba as India,” says Amal Pullarkkat, member of the Students Federation of India and former vice president of the Jawaharlal Nehru University Students’ Union (JNUSU). “In India, we are battling a different set of problems—patriarchy, communalism, hindutva, and so on—but we seek inspiration from Che and his fighting spirit.”

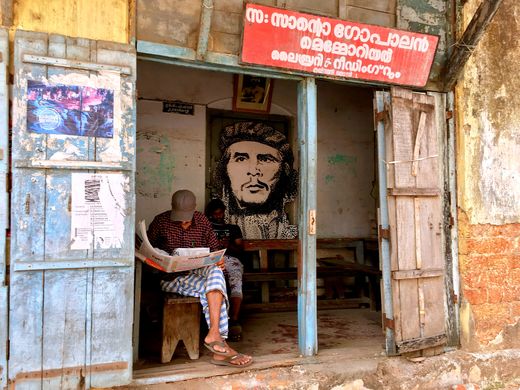

Legend sans borders: Santo Gopalan Memorial Library and Reading Room at Fort Kochi in Kerala. On the wall is a rendering of Alberto Korda's famous photograph of Che | Bhanu Prakash Chandra

Legend sans borders: Santo Gopalan Memorial Library and Reading Room at Fort Kochi in Kerala. On the wall is a rendering of Alberto Korda's famous photograph of Che | Bhanu Prakash Chandra

But, what is it that sets Che apart from Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels and other icons of communism? It could be that none of them were photographed by Alberto Korda. Che’s enduring pop culture legacy owes a great deal to a single photograph taken by the Cuban photographer on March 5, 1960, when Che was 31 and at the peak of his revolutionary life. Called ‘Guerrillero Heroico’ (Heroic Guerrilla Fighter), it shows Che attending a memorial service for those who had died when a freighter carrying munitions exploded in Havana. According to Korda, who was Castro’s close friend and official photographer, Che’s facial expression at that melancholy moment showed his characteristic stoicism and “absolute implacability”.

Eight years after Korda shot the picture, and a year after Che died, Irish artist Jim Fitzpatrick did a stylised red-black-and-white rendering of it, which became so popular that, to borrow Fitzpatrick’s own words, the image “bred like rabbits”. Artists across the world began to make their own versions of Guerrillero Heroico.

“It’s probably the most reproduced profile picture in history,” says Vimal Menon, Bengaluru-based artist and photographer. “It’s so famous that one could argue that Che’s enduring fame rests on the varied simulacra based on that picture, and the fact that he died young. Of course, there is no denying that Che was a big revolutionary; but then, why wasn’t he so famous when he was alive?”

Amal, however, believes Che’s fame rests largely on his relevance in today’s politics. “Che’s pictures have been used to adorn bars and pubs and other such establishments, mainly because of his model-like good looks. There is a certain commodification that is happening. But it is happening because Che is still relevant,” he says. “He upheld an ideology, which he explained very well through his writings and deeds, and that forms the basis of his popularity.”

Che is so revered, especially among the youth in Kerala and West Bengal, that there are clubs, libraries, town squares and even bus shelters named after him. But it would be hard to deny that his standing as a left-wing icon owes a lot to the one group he so detested—capitalists. Posters and watches, bags and bandannas, mousepads and bedsheets…. It is hard to find products or accessories that Che’s image has not adorned. His face has become a kind of universal insignia of dissent—wearing a Che T-shirt, for instance, could make you an instant rebel.

Brand consultant Harish Bijoor says Che has become an “eternal brand”, one that has “outgrown” the ideology he stood for. “I don’t think that Che [the brand] is helping the leftist cause at all,” he says. “He has grown beyond the left. I would even say that Che today is making a rightist statement.”

According to Shehla Rashid, member of the All India Students Association and former vice president of JNUSU, Che’s image is being “decontextualised”. “What happens often is that Che is perceived as a rebel without a cause, when in fact he is a rebel who is very much with a cause,” she says. “That cause has been decontextualised, and relegated to the background.”

But Brand Che may not be such a bad thing, after all. “It can be a double-edged sword, [in the sense that] it could become an entry point,” says Shehla. “You start with a T-shirt, then you find out who he is, then you find out about communism…. It would be interesting to do a research on whether people read about communism first and then get to know Che, or come to know Che first and then communism.”

Chances are that you would buy a Che T-shirt first, before you choose to become a communist. It could be a case of what Lenin envisaged: The capitalists selling the ropes with which the communists will hang them.