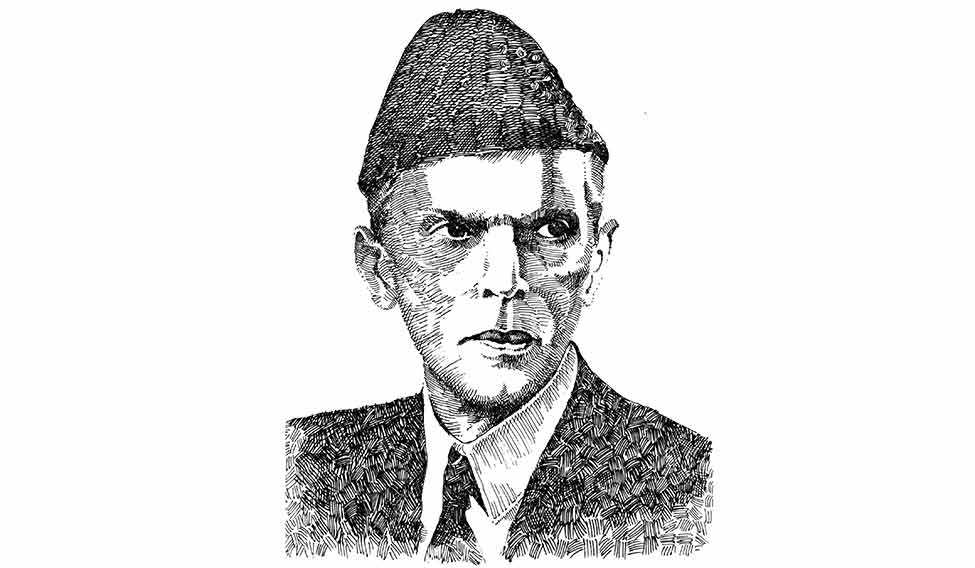

The life of Muhammad Ali Jinnah and his contributions to the political destiny of South Asia are remarkable, although understood differently in India and Pakistan. He remains an enigma to many—once acclaimed as the ‘ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity’ by Congress stalwarts like Bal Gangadhar Tilak and Sarojini Naidu, he became instrumental in the making of Pakistan. A rare genius that he was, Jinnah combined in himself different roles—that of a lawyer, a great orator, a practical negotiator, an effective bargainer, and a statesman with unfinished innings in the nation building of Pakistan. Jinnah had several facets to his complex personality and seemed, at times, paradoxical.

Jinnah was born in 1876 in Karachi in a Gujarati merchant family from the Ismaili Khoja community. Though trained for a commercial career, he realised that a legal profession would be his best bet. He joined the Lincoln’s Inn in England where he had his first ‘internship’ in politics. It was at this time that Jinnah worked for the election of Dadabhai Naoroji to the British parliament. He unmistakably inherited the western liberal traditions which helped mould his legal as well as political career in India.

Joining the Congress in 1906, Jinnah became associated with stalwarts like Pherozeshah Mehta, Gopal Krishna Gokhale and Tilak. He joined the Muslim League only in 1913, and was instrumental in the making of the ‘Lucknow Pact’ in 1916 when the Muslim League and the Congress agreed on separate electorates. He also played a leading role in launching the Home Rule movement.

However, Jinnah’s disapproval of mass politics, with religion taking a lead role, was perceptible in the 1920s. This was first evident in 1920 when he opposed Gandhiji’s non-cooperation movement. At this stage he favoured a constitutional movement for dominion status based on the recognition of special privileges for Muslims. Rejection of his proposals for sharing of power and seats led to a fissure in the nationalist movement, manifesting in Jinnah’s 14 points submitted for the Round Table Conference of 1930.

However, when elections were announced under the 1935 Act, Jinnah was pressured to come back from London and take up the leadership of the Muslim League. But the elections, held in 1937, deteriorated the relations between the Congress and the League. Disgruntled with the ‘politics of exclusion’, Jinnah proceeded to conceptualise a ‘two-nation’ theory, putting the idea of ‘Muslim homeland’ across the table of bargain.

This idea found a strong plea in the Lahore session of the League in 1940, which passed the ‘Pakistan Resolution’. Since then each negotiation ended up in a fresh round of controversies. As the Cabinet Mission proposal also fell through, Jinnah got an incomparable wedge to press more vigorously for Pakistan. The partition plan eventually resulted in the birth of Pakistan and Jinnah became its governor general. His first address to Pakistan’s Constituent Assembly on August 11, 1947, however, gave an indication that the new Muslim state would not be a theocratic one, with complete freedom assured to all to follow their beliefs and practices. Yet, the nation building process along these lines did not continue in Pakistan as he died in 1948. The political vacuum created by his demise ushered in a new cycle of state and nation building crises in Pakistan.

Jinnah was never an orthodox Muslim embedded in the doctrine of scriptures, nor was he a disdainer of them. He was a gifted speaker with an undiminished vigour, amazing sweep and range of ideas. Opposing all dogmatic theories, Jinnah used to marshal arguments with the mastery of a consummate general. The distinguishing character of his dynamic idealism was a deep liberal, secular-nationalist outlook which, however, found critical encounters with the trajectory of the composite Indian nationalism.

Although Jinnah worked for Pakistan in the last decade of his career under conditions of political expediency, his vision and outlook essentially sought to sustain an inclusive, participatory system of power sharing without disrupting cultural dynamics of social relations. The post-partition challenge before both India and Pakistan is how to ensure this social balance of power against all odds. Though India has a moderately successful path, Pakistan is still struggling to find answers to the questions of nation building after partition.

K.M. Seethi is professor and director, School of International Relations and Politics, Mahatma Gandhi University, Kerala.