The de facto border between India and China is the 3,500-km Line of Actual Control (LAC), which runs southwards from Jammu and Kashmir to Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh, Sikkim and Arunachal Pradesh. There are at least a dozen separate and specific disputes along the LAC, apart from the broader territorial disagreements between the two countries.

Most disputes along the LAC are of little strategic importance, as they are centred on the right of possession of ridges and meadows. There have been intermittent fisticuffs and eyeball-to-eyeball confrontations along the LAC, but no shots have been fired since 1975. The squabbles stick to unwritten rules.

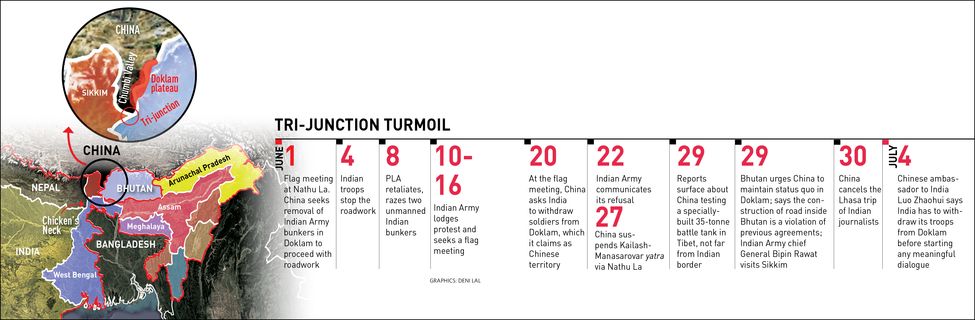

That is why the Chinese belligerence in Chumbi Valley confounds experts. Strategically, China’s position in the region is its weakest along the LAC. The valley is a wedge-shaped territory that juts out southwards from the Tibetan plateau, and ends southwest of Doklam plateau. Further south is the India-China-Bhutan border tri-junction. Doklam spans around 200 square kilometres, and is claimed by Bhutan; but at least one-third of it is under Chinese control.

Political maps show Chumbi Valley as a dagger roughly pointed at ‘Chicken’s Neck’, a sliver of Indian territory in West Bengal known as Siliguri corridor, which connects northeastern states to the mainland. The fear is that the Chinese could overrun Indian territory south of Chumbi Valley, and cut off the Neck and, thereby, the northeast from India.

Experts say the fear is overblown. “You have to look at the relief map to get the correct picture,” says Lt Gen (retd) Thomas Mathew, who served in the region. “Doklam is an isolated area, at the tip of the Chumbi Valley. We have posts on our side, and it is almost impossible for the Chinese to develop an offensive there. Theoretically, there could be a threat to Siliguri corridor, but coming down [southwards] from the valley would be a Herculean task.”

That task would involve the Chinese building heavy-duty roads (which they have been) and facilitating large-scale movement of troops and equipment—which they cannot. The reason is that India controls the heights surrounding the narrow end of the valley. The Army’s three pivot corps in the east—Dimapur, Tezpur and Siliguri—can easily airlift 155mm guns to the area, and then pound enemies to hell, high water or Shangri-La.

“The terrain is so rough that it makes troop movement very difficult for China,” says Mathew. “It would be like trying to move a lot of cars through a track that is so narrow that only one car can go at a time. In my opinion, the Chinese are just trying to create a pinprick there.”

If so, they have surely succeeded. But, perhaps, the real intention could be to drive the Chumbi wedge between India and Bhutan. As per the 2007 Treaty of Friendship, India and Bhutan are supposed to “cooperate closely with each other on issues relating to their national interests”. It means India would have to step in if China decides to take drastic measures to end its border disputes with Bhutan.

There is little chance of China doing that, but it can certainly create situations that can make Bhutan perceive India as domineering. The ongoing India-China standoff, for instance, is happening over territory claimed by Bhutan. Yet, Bhutan chose to officially respond to it only two weeks after India began making noises.

The Chinese could well be trying to shake things up to change the equation in Chumbi Valley. Geography, however, wouldn’t allow them that.