In August, Dana Majhi, a resident of Melghar village in Kalahandi district of Odisha, became ‘breaking news’ as he walked 10km carrying his dead wife, Amang Dei, on his shoulders. The fact that the hospital where she died of tuberculosis could not get him an ambulance was just a minor, though tragic, part of the infirmities that plague the health care system in India.

In June, 16 patients reported vision loss after cataract surgery at a government hospital in Salem district, Tamil Nadu. The loss of vision was owing to an infection post surgery.

Around 3,000 children die of malnutrition in India every day. Lakhs of them suffer and succumb to diarrhoea, a disease associated directly with drinking water and sanitation. India has the highest number of child (under five years) deaths in the world. Thousands of mothers die during and after childbirth.

This in a country that boasts hi-end technology, state-of-the-art laboratories and operation theatres, one that is best in patient care in the private sector and takes pride in its premium medical institutes such as the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (New Delhi), the Christian Medical College (Vellore) and the Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research (Chandigarh). India’s medical tourism was worth US$ 3 billion last year and is growing. Indian hospitals are treating patients from across the world including some European countries as well.

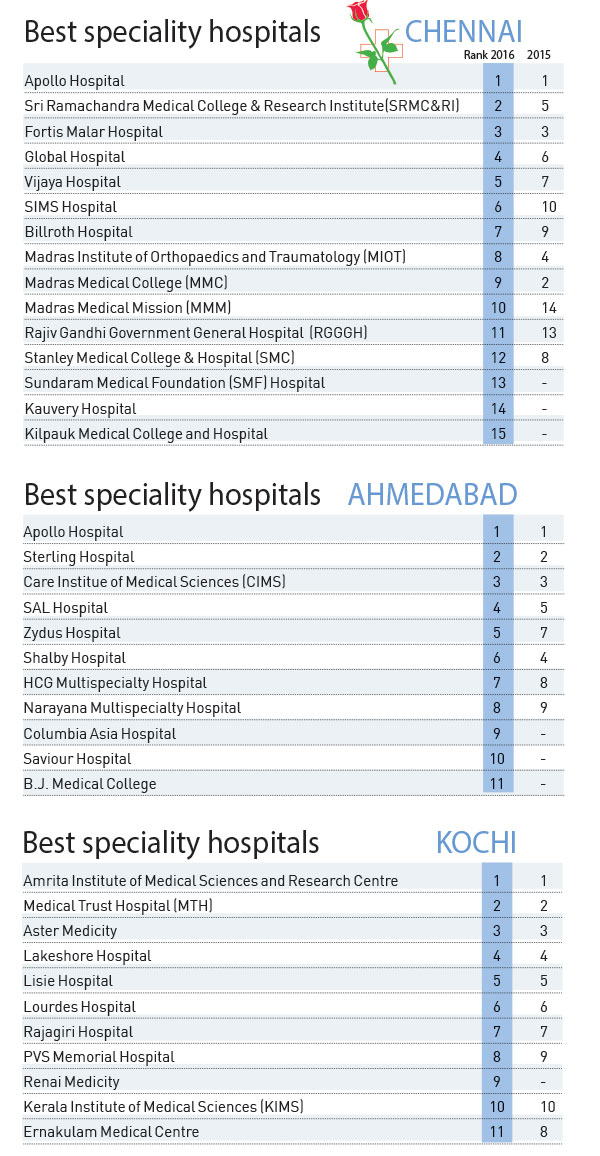

A look at THE WEEK-Nielsen Best Hospitals Survey 2016 will tell you that we have no dearth of world-class private hospitals. But the same cannot be said about our government hospitals. There is a huge gap between primary and tertiary health care systems in India. In an ideal situation, health care is provided at three levels—primary health care that takes care of a small population and looks after their day-to-day health problems; secondary health care that deals with slightly more complicated health issues, and tertiary care centres that deal with complex medical issues and provide specialty care.

The problem with India’s public health system is that its primary and secondary health care systems lack basic infrastructure, manpower and required skills. The reason, say experts, is the severe shortage of funds in the health sector. Out-of-pocket expense on health is pushing thousands of people living on the margins into poverty every year, which is further burdening the crumbling health infrastructure of the country.

The World Health Organization recommends that the government should spend at least 5 per cent of the GDP on health; India spends only 1.2 per cent. “This lack of money doesn’t allow any reform in the ailing health infrastructure, which includes facilities for health care providers as well as building of hospitals, procurement of health equipment and medicines,” says Dr J.S. Thakur, professor, School of Public Health, PGIMER, Chandigarh.

“The government introduced ten AIIMS-like institutes but it forgets that it is not the building that has made AIIMS, AIIMS. It is the faculty, its experience and its legacy. Go to any of the new AIIMS and you will not find enough experienced doctors. The reason is that the government has failed to provide a good living environment to the doctors who are willing to go to these places and work,” says Dr Amod Gupta, former dean, PGIMER, Chandigarh.

Doctors say lack of living as well as working facilities is the reason why there are not many doctors to fill the 40 to 60 per cent vacant posts in rural India. So, rural population has no alternative but to move to cities for their medical needs.

“If the government can fill these vacancies at primary health centres, it can meet 70 to 80 per cent health care needs of local people. It will not only save the lives of the people but also reduce the burden on tertiary care centres in the cities,” says Thakur. “Lack of infrastructure at the primary and secondary health centres burdens the tertiary care centres and more so the referral centres like PGI and AIIMS. We are working 200 to 250 times our capacity.”

Bitter pill: Though patients get free medicines at public health centres, many a time the medicines don’t reach them owing to lack of funds | Sanjay Ahlawat

Bitter pill: Though patients get free medicines at public health centres, many a time the medicines don’t reach them owing to lack of funds | Sanjay Ahlawat

Another problem with our public health care system, says Dr Malatesh Undi, a Bengaluru-based public health specialist, is the lack of data on diseases. “If we are unaware of the exact extent of the problem, finding effective solutions would be difficult. This again is because of lack of funds and trained manpower to collect and analyse data,” he says.

It is unfortunate that even after 70 years of independence, India has failed to create a safe, affordable health care system in the country. Providing medical care in the rural and remote terrains has always been a challenge. The government has made some efforts and has come up with a few innovations such as mobile clinics, portable laboratories and boat clinics to reach out to these people, but these are grossly inadequate.

In fact, India has followed some of the unhealthiest ways to meet health challenges of the country. Take, for example, sterilisation of women in camps. It was a normal practice till the Supreme Court banned it in September. Thirteen women died at one such sterilisation camp in November last year. That, however, was not the first time. In 2006, in response to a public interest litigation that listed the deficiencies in the camps, the Supreme Court issued guidelines for conducting mass tubectomies. According to these guidelines, states were to set up a panel of approved doctors to operate in the camps. Women undergoing tubectomy were to be counselled and insured and be operated upon only after due consent. But these panels didn’t do enough to ensure safety of women. Also, sterilisation camps highlight the desperation of these women who suffer from multiple pregnancy and the failure of family planning programmes in the country.

Similar camps are being organised to treat eye problems, and thousands have lost their vision after undergoing cataract surgeries in such camps. “Camps, be it at a school, an inn or a local hospital, are a bad idea because dealing with a large number of patients is impossible. To conduct eye surgeries at such a scale require huge infrastructure, highly trained technicians and more than one doctor, which are not available. To maintain aseptic conditions throughout a camp is not possible,” says Gupta.

What the government doesn’t realise is that a building doesn’t make a hospital. For a building to become a hospital, there are certain guidelines that are followed worldwide—maintaining aseptic conditions throughout, hi-end filters to filter out any germ in the operation theatre and other sensitive areas, and maintaining positive air pressure in the operation theatre and negative air pressure in isolation units. Not many hospitals in India are equipped with facilities necessary to avoid hospital-acquired infections. There are many hospitals that do not even have a continuous supply of electricity. “It is all because we are not spending enough on health care. When there is a shortage of funds and we are hard-pressed to meet the basic needs of medicine, creating world-class environment for health care is a far-fetched dream,” says Gupta.

India takes pride in the fact that it eradicated smallpox in the 1970s and polio in 2012. But are we taking health challenges such as malaria, dengue, Japanese encephalitis and non-communicable diseases seriously? Non-communicable diseases such as hypertension, diabetes, coronary artery disease and cancer are spreading like an epidemic in the country. “It is a scary situation because all these diseases require a huge investment in treatment. As we are short of funds, the only solution we have is to prevent them from happening. Any further delay in these measures would be disastrous,” says Thakur.

Unkind cut: Sterilisation of women in camps was a normal practice till the Supreme Court banned it in September | Reuters

Unkind cut: Sterilisation of women in camps was a normal practice till the Supreme Court banned it in September | Reuters

Health needs specialist care in the country. Every state has a different health challenge. A study done by the School of Public Health found high prevalence of obesity and related hypertension and diabetes in Punjab. The main reason, they found, was the consumption of alcohol and tobacco, high-fat diet and lack of physical activity. Another major health problem in Punjab is the high incidence of cancer owing to high use of pesticides and insecticides on crops. “Farmers are using a high level of insecticides to protect their crops and they have restricted their consumption of fruits and vegetables, which has led to increase in chronic ailments such as obesity, diabetes and hypertension,” explains Thakur.

Kerala and other southern states, too, are fighting the menace of non-communicable diseases. Diabetes is on the rise here because of lifestyle and dietary habits. Eastern states such as Bihar, West Bengal and Odisha, on the other hand, are grappling with vector-borne and infectious diseases.

Doctors say the government should take concerted efforts to deal with the ailing public health system and raise a brigade of highly trained, skilled team of medical professionals—both doctors and technical staff—to meet the country’s growing medical needs.

NEW HOPE

Dr Prakash Kothari, Mumbai-based sexologist

The next great thing in sexology could be an effective medication for erectile dysfunction and early orgasm without any side effects. Attempts are being made to find herbs for the replacement of male and female sex hormones. Sexual aids that can provide complete satisfaction to an individual when the partner is away or absent may also be developed in the next few years.

NEW HOPE

Dr Devi Prasad Shetty, cardiac surgeon and founder of Narayana Health, Bengaluru

One of the big things of the future is artificial hearts. We have been implanting artificial hearts or left ventricular assist devices for the last eight years and some of these patients are doing extremely well. Apart from swimming, they can do everything.

The biggest problem in propagating artificial heart implant is the high cost. Though companies have reduced the price, it still costs Rs 45 lakh. The price, however, will soon come down.

Within the next 10 to 15 years, I feel most people who die will still have a functioning heart. Of course, it is an artificial heart that you have to turn off before doing the last rites.

Today we are replacing heart valves. It is a matter of time before we replace the whole heart with an artificial heart. Soon, replacing the heart with a mechanical heart will be a reality.

Very few people are aware that heart attack can be predicted at least 10 to 20 years ahead just by doing an Ultrafast CT scan, which takes less than five seconds. We get upset when we hear about young people dying on treadmills. All these deaths could have been prevented had they done the Ultrafast CT scan. Predicting heart attacks ten years ahead is going to be the game changer in managing heart attacks.

How we did it

THE WEEK-Nielsen Best Hospitals Survey 2016 was conducted through face-to-face and online interviews among 2,183 specialists and general practitioners in 18 cities from September 8 to November 2.

City-wise sample size: Ahmedabad (121), Bengaluru (119), Bhopal (120), Bhubaneswar-Cuttack (121), Chandigarh (122), Chennai (112), Coimbatore (109), Delhi NCR (127), Hyderabad (120), Indore (126), Jaipur (120), Kochi (130), Kolkata (125), Lucknow (121), Mumbai (139), Nagpur (118), Pune (122) and Thiruvananthapuram (111).

Parameters: Competency of doctors, patient care, availability of multispecialty, overall reputation, infrastructure and innovation in treatment and hospital environment

Doctors were asked to nominate:

* *Top five multispeciality hospitals at all-India level, and at zonal level

* *Top five multispeciality hospitals and critical-care hospitals each in their cities

* *Top five hospitals in their specialty

* *Top five medical colleges in India as well as in their zones

* *Top five hospitals in terms of research facilities and output