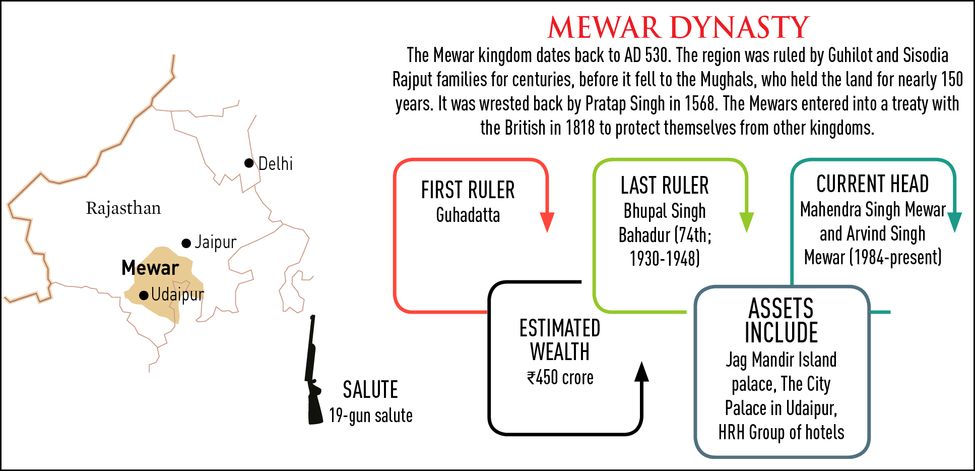

The City Palace in Udaipur seems to rise from the edge of the sapphire water of Lake Pichola, and it meanders along for a good 2.5km. Most tourists find it difficult to find the best photo spot in the palace—every backdrop is prettier than the other. The many galleries in the palace display all that the Maharanas of Mewar owned—from the brocade and chiffon of generations of maharanis to the angrakhas of the men, jewellery, paintings and the sculptures. There are musical instruments, armoury, silverware and crystal ware. A silver palna (cradle) and the silver mandap made for the wedding of princess Padmaja in 2011 also find a place.

The palace is a mini empire of Arvind Singh Mewar. Shriji, as he is affectionately called, was four years old when his grandfather Bhupal Singh, the 74th Maharana of Mewar, was at a crossroads. Bhupal Singh said on April 18, 1948: “My choice was made by my ancestors. If they had faltered they would have left us a kingdom as large as Hyderabad. They did not. Neither will I. I am with India.” And, Mewar became the first princely state to merge with the state of Rajasthan, and then became part of India.

The royal life in Udaipur, however, remained large, with pomp and show, silver and gold, chiffon and brocade. When Shriji was 12, his father, Bhagwat Singh, received an invitation from prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru to visit the Red Fort. The Maharanas had “resolutely upheld an ancient vow of their family never to enter Delhi so long as it remained in the hands of a foreign power”. Bhagwat Singh went because the foreign rulers had gone. “The effect of his visit was a powerful inspiration to free India, an endorsement of the supreme prize of Independence,” said British historian Brian Masters, author of Maharana—The Story of the Rulers of Udaipur.

That, however, did not stop Bhagwat Singh from pondering the future of Mewar, particularly the palaces whose maintenance needed the privy purse that supplanted the internal state revenues. He established a private company and sold some of the palaces to this company. One of those became the luxury Lake Palace Hotel. It was a success. Among the string of visiting dignitaries to Udaipur were Queen Elizabeth II and Jacqueline Kennedy.

Shriji was 25 when the royals were stripped of their titles and the privy purses were abolished. In fact, prime minister Indira Gandhi sought the help of the Maharana to “do away with certain institutions without any intention to cause hardship to the rulers or to injure their self respect”. Bhagwat Singh replied that hardships were to be endured, but not dishonour. He created a trust and made Arvind Singh its managing trustee.

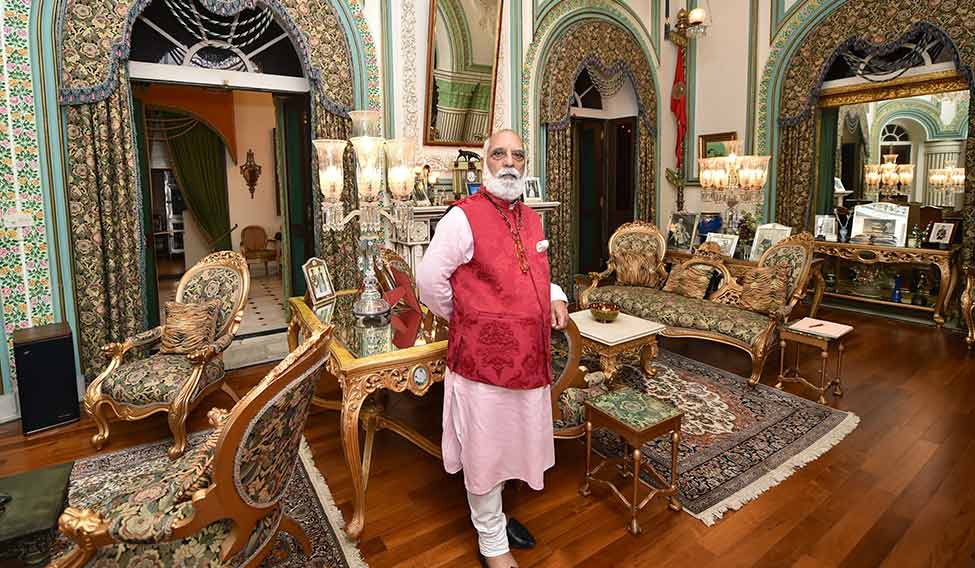

But 70 years after independence and 48 years after the abolition of privy purses, Shriji is the Maharana as far as the people of Udaipur are concerned. As chairman of Historic Resort Hotels, he is hands on with the larger purpose of doing his duties towards the people as well as the monuments and culture that he inherited.

The City Palace had 800 visitors a day in 2003. Today, it is about 3,000 a day. There are 2,000 employees on its rolls, and about 40 per cent of Udaipur’s residents depend on the palace for their livelihood. “Ours is the only museum without a Hindi audio guide,” said Mayank Gupta, deputy secretary (development) of the Maharana of Mewar Charitable Foundation. “Shriji would rather let the 400 Hindi-speaking guides earn a living as they take visitors through the palace and the museums.”

Standing tall: The City Palace, Udaipur | Aayush Goel

Standing tall: The City Palace, Udaipur | Aayush Goel

In the gallery of crystals on the first floor of the Durbar Hall complex, there are thousands of pieces on display, ranging from a poster bed to tables and vessels. Said Gajendra Singh, the curator: “These were lying packed just as they had been received for 120 years till Shriji decided a few years ago to open and display them in a museum here.” Apparently, they were ordered by Maharana Sajjan Singh and were delivered from Belgium when Fateh Singh was the ruler. Since he led a spartan life, Fateh Singh did not even open the crates.

The gates of Shambu Niwas Palace, flanked by the large Shiv Niwas Palace and Fateh Prakash Palace, are never closed. A beautiful garden with a marble fountain and lamps leads one to the waiting room. If water gushes up the fountain, people know Shriji is in. He owns two dozen vintage cars that are on display at a museum in the former Mewar State Motor Garage. His favourite is a 1924- Morris Green. All the cars are taken out daily for a round in the museum garden, but are not to be taken out of the City Palace.

A passionate chef, Shriji hosts high style food shows on television. “But the fare on his table is a different story. Shriji’s is a two course lunch—the one from his own kitchen is largely Rajasthani, and the other anything from any of the hotel restaurants. He decides in a random way. The idea is to track the standard of food they are serving. Similarly, when he walks around the garden, a gardener will have to tell him why a particular lemon tree in the Shambhu Niwas Palace has fewer lemons this season!” said Jyoti Jasol, whose family has known the Mewar royals for four generations.

The ceremonial attire of the Maharanas is not as bejewelled as those of Mysore, Hyderabad or Gwalior royals, said Smita Singh, textile conservation consultant at the Maharana of Mewar Charitable Foundation. “Shriji prefers cotton kurta pyjama for casual wear, and formalwear are traditional silk kurta pyjamas, brocade sadri, fulgar or angrakha, along with jewellery and turban made in the palace for generations by the in-house tailoring department,” she said.

In the past 70 years, much has changed for the royalty. But Shriji points out that nothing changed overnight. “The sun did not suddenly start rising in the west or setting in the east! It was a slow process of handing over Mewar to Rajasthan, and the state of Rajasthan to India. All those memories are quite vivid. I feel nothing in life is stagnant. Life itself is dynamic. So our struggle before 1947 was different. At the same time, definitely related to keeping not only our territory free and unoccupied, but also this portion of India free. And, after that came our own institutions, freedom under the Constitution. That is what has changed,” he said.

Life, however, goes on. “We continue to be very time table and timing oriented,” he said. “What have become different are the pomp and show, the regalia, those have definitely reduced. We also don’t believe in that. But we do believe in the religious side and the religious significance of these. The festivals were celebrated because they always synchronised with the weather, the climate, the time of the year, and there was a hidden meaning. It is those things that we like to bring out and share and celebrate, it was never for pomp and show.” These events are still grand and colourful, with people participating in large numbers.

The environment in which his son, Lakshyaraj Singh, 31, grew up was entirely different. “The circumstances, the timing, the conditions were different,” said Shriji. “The environment in which we are living now is different, the thinking process is different, the future is different.”

Lesson, legacy: A school run by the Maharana of Mewar Charitable Foundation | Aayush Goel

Lesson, legacy: A school run by the Maharana of Mewar Charitable Foundation | Aayush Goel

Shriji’s journey from being a prince to the chairman of the Historic Resort Hotels group is a lesson in transformation and management. The vision, he said, came from his father, who gave him all that was necessary in life, including education and exposure. He studied in the US but chose to return and play the role he was destined to. “I chose to do this; it was not as if it was thrust on me. I did want to fly a plane, but not to be a commercial pilot,” he said.

Lakshyaraj was like any other boy in the city and in school. “How are we different? We are all alike. We are not born with the knowledge of our history. We learn as we go along,” said Shriji. He does not consciously sit down Lakshyaraj and tell him about this legacy and heritage that one day will become his responsibility. It comes up in the course of their chats and casual conversations.

From the huge structures to the items on display at the galleries, everything in Lake Palace represents the dynasty’s heritage. Shriji has repaired, renovated, restored and conserved them in a way that the plumbing and electrical lines do not spoil the magnificent period structures. The ancient palaces complete with the zenana and mardana spaces, the durbar halls, and even the royal stables, were converted into hotels, restaurants, museums, galleries, conference halls, research centres, schools and libraries.

Through the Maharana of Mewar Charitable Foundation, Shriji supports a host of initiatives for people in need. Politics, however, is a strict no because of the historic vows to the deity Eklingji. Shriji said these were self-imposed codes of conduct. But he is “very, very particular about exercising my right to vote.”

The Maharanas saw themselves not as kings, but custodians of Mewar, representing and executing the duties on behalf of Eklingji, Lord Shiva. Like every Maharana before him, Shriji unfailingly visits the shrine of Eklingji, about 21km from the City Palace, every Monday evening. What does he pray for? “Well-being of everybody, quality of life for all.”