The instructions were very clear. No intoxicants should be consumed before rafting. That meant no cheap daru (liquor) or chillum hits with enlightened sadhus that you found passed out on the roadside. As soon as our designated raft landed on the banks of Shivpuri in Rishikesh, our guide laid out the basic commandments of the whitewater river rafting sport. Rule 1: Thumbs up, fingers down. Never lose grip of your paddle, which could be your greatest friend in times of trouble. Think of it as an extension of your arm, only more useful. Rule 2: Always keep an ear out for instructions from the guide and learn to decipher them over the collective screams of terror or thrill from your fellow rafters. Paddle forwards, backwards or stay still accordingly. Rule 3: Once in the raft, anchor your legs. If you hear the command ‘Get down’, cower like you never cowered before. Imagine you 'heard' a police jeep pulling up while you were blowing smoke rings into the sadhu's face.

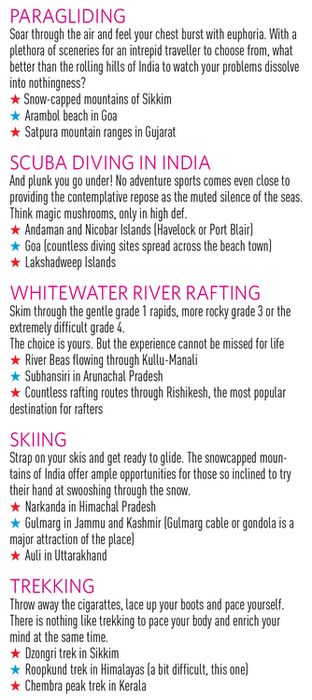

Whitewater rafting, the signature sport of Rishikesh, has a deep-rooted connection with the mountain city. It was offered, for the first time in India, in Shivpuri in the late 1980s. Since then, the business has mushroomed, resulting in over 140 operators offering their services with the recognition of the Uttarakhand government. Rafting can be attempted from a 9km stretch, which would be covered in approximately an hour and fifteen minutes, to a 36km stretch, which would take around six hours.

With the basic instructions in mind and a few dry runs to get the hang of paddling in sync, the raft took off—the first rapid, where the water morphs from calm green to a tempestuous frothing white, was already within our range of vision. Rapids, areas in the river with higher velocity and turbulence, are broadly classified into grades one, two, three and four depending on their hazard quotient and difficulty in manoeuvrability. Grade one rapids are the easiest to tame, ideal for children and novices. As the grade increases so does the difficulty. Grade four rapids, say tour operators at Rishikesh, are almost impossible to cross without toppling over. In the Rishikesh stretch there are around 15 of them, with colourful names like Return to Sender, Cross Fire, Golf Course and Roller Coaster. The Wall (grade four plus), is generally considered the Mount Everest of Ganga rapids, almost impossible for the inexperienced to negotiate.

It was grade two rapids that lay ahead of us, we were informed. The instructions were clear: In the event that you lose balance, keep calm and try to float on your back with legs pointing in the direction of the current. Any attempt to paddle with your feet could result in possible injuries from sharp rocks that protrude just below the surface of the water. In a record time of less than a few minutes—courtesy our uncoordinated clownery—the first crew member fell overboard, while the rest of us brave hearts abandoned our posts and assumed foetal positions in the centre of the raft to avoid the lashing waves. The unfortunate soul was rescued, hauled in by the scruff of his life jacket, barely a minute later, jubilant and wet but none the worse for wear. (The guide has a rescue rope in hand, long enough to tow someone in, should they float too far away from the raft). Grade two rapids were more enjoyable—a zigzag experience where you don’t actually lose control of the raft. But the grade three and higher rapids (Golf Course, Roller Coaster with deep peaks and troughs), which we encountered, were the real deal; they could muster enough firepower to toss the raft around like a rag doll.

Any moderately fit person, irrespective of gender, can attempt river rafting, which involves bouts of paddling interspersed with moments of relaxation where you let the river currents do the task for you. The curse of a sedentary lifestyle could manifest in the form of dull aches in arms and shoulders the next day, but nothing worse. “Contrary to popular perception, it is a very safe sport. It is perfectly safe for non-swimmers as they are provided with all protective equipment like life jackets,” says Sandeep Rana, who has been working as a whitewater rafting guide for eight years. “The main problem is that some people don’t disclose that they have asthma or heart conditions when we ask for their medicals. That could cause unexpected issues.”

Numerous camps, in and around Rishikesh, offer attractive packages for a combination of village and forest treks, rafting, bungee jumping, zip lining, rappelling and such adventure activities, apart from in-camp activities like bonfire and sing-alongs. The cost varies (starting from Rs 2,000) depending on the season and whether you opt for two-day or three-day packages. From our vantage point at a camp in Malaghat (the mountains are identified based on the names of the villages or settlements located there), the view was glorious. Imagine waking up and opening your tent flaps to the sight of the Himalayas on all four sides, cradling Ganga in its bosom. Once in a while, a devotee would emerge out of a distant vehicle to offer prayers by the river. An occasional spurt of activity from the agrarian settlements on the hills—rustic havens of winding forest paths, unique deities and fields of tomatoes and pulses—would mar the opaque layer of comfortable lethargy.

Feet on solid ground: Rafters disembark at an interim stopover point at Rishikesh | Aayush Goel

Feet on solid ground: Rafters disembark at an interim stopover point at Rishikesh | Aayush Goel

The surroundings invoked memories of my childhood pilgrimages to Rishikesh; a time I was still young and terrified of entering the Ganges, should my leg get bitten off by an alligator (thank you, Arthur Conan Doyle!). I remembered the awe-inspiring sight of a group of eight teenagers linking hands and diving into the most turbulent stretch of the Ganges with no protective equipment whatsoever. “They would keep on floating with the currents. A few kilometres away, there is a rock that they would use to break away from the tides,” our guide then had said. Was it still a thing? I asked the overseers at the camp. “Yes. Sometimes, the youngsters attempt to swim across the river. They would even float along with the rafts, grasping on the rope that extends from it,” says supervisor Rajinder Rana.

But the calm hues of the Ganga can be deceptive, as the local residents know only too well. “In June 2013, the river rose by 20 feet or so,” says Rana, who is also an ex-serviceman, referring to the devastating Uttarakhand floods, which caused more than a thousand deaths. “Numerous camps by the base of the hills were completely washed away. Even though the settlements were situated at a safe altitude and remained unaffected, I remember the sight of the muddied waters and the debris that floated along. I don’t think even the authorities could comprehend the levels to which the river would rise.” Luckily, he says, casualties were not reported in his area as it was the rainy season when the camps were all packed up and deserted. So, what about the Ganges? Over the years, has there been any visible change in its nature? “There are three dams in the Alaknanda and a big one in the Bhagirathi, both of which are tributaries of the Ganga combining at Devaprayag,” says Rana. “The river has slowed down quite a bit, become calmer in a sense. After the floods, the river gouged out land and widened at some places, while collapsing boulders narrowed its turf at others.”

Often, the sport offers more than a few hours of thrill or adventure—the rafters play a silent, unheeding witness to the sheer beauty and volatility that are ingrained in the great forces of nature. At times calm, at times disturbed, the unpredictable fits of enraged turbulence. In a grade three rapid that we crossed , the debris of a bike—a relic of the 2013 carnage—could be seen still lodged in the powerful eddies. The river never forgets, neither does she let anyone.