At first sight, there is nothing common to a municipal corporation office in Siliguri, West Bengal; the highly secured rooms and corridors of Parliament House, New Delhi; a Tempo Traveller cruising the streets of Chennai; a sprawling house in Kanichukulangara in Kerala; the VVIP lounge in airports at Guwahati and New Delhi; an anonymous house in Virungambakkam, Chennai; and cramped bedrooms in Ballygunge and Salt Lake City, Kolkata. These unusual locations, however, helped birth natural and unnatural alliances in four states where assembly election results will influence politics at the national level.

The Tempo Traveller, the most unlikely germinating ground, is where top political leaders in Tamil Nadu plotted an alliance. P. Vaiko of Marumalarchi Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam, Thirumavalavan of Vidhuthalai Chiruthaigal Katchi, G. Ramakrishnan of the CPI(M) and R. Mutharasan of the CPI—part of the People's Welfare Front in Tamil Nadu—clocked many miles stitching together an unusual front by roping in Desiya Murpokku Dravida Kazhagam and Tamil Maanila Congress.

Far from the bustle of Chennai's roads, two air-conditioned rooms in Parliament House saw the birth of the country's most inorganic alliance. In one room sat CPI(M) general secretary Sitaram Yechury; Congress MP Pradip Bhattacharya occupied the other. Here, the two leaders carried on secret talks for a seat adjustment between the CPI(M) and the Congress, sworn political adversaries for five decades, to take on common enemy Mamata Banerjee in West Bengal.

A few kilometres away, in the VVIP lounge of the Delhi airport, BJP general secretary Ram Madhav reached out to Bodoland People's Front leaders to form a broad alliance against the Congress in Assam.

Down south, Vishva Hindu Parishad leaders persuaded a clutch of Hindu caste organisations to come together to form a party and align with the BJP. The discussions reached a climax at the Kanichukulangara residence of Vellapally Natesan, under whose guidance the Bharath Dharma Jana Sena was formed.

Illustration: Job P.K.

Illustration: Job P.K.

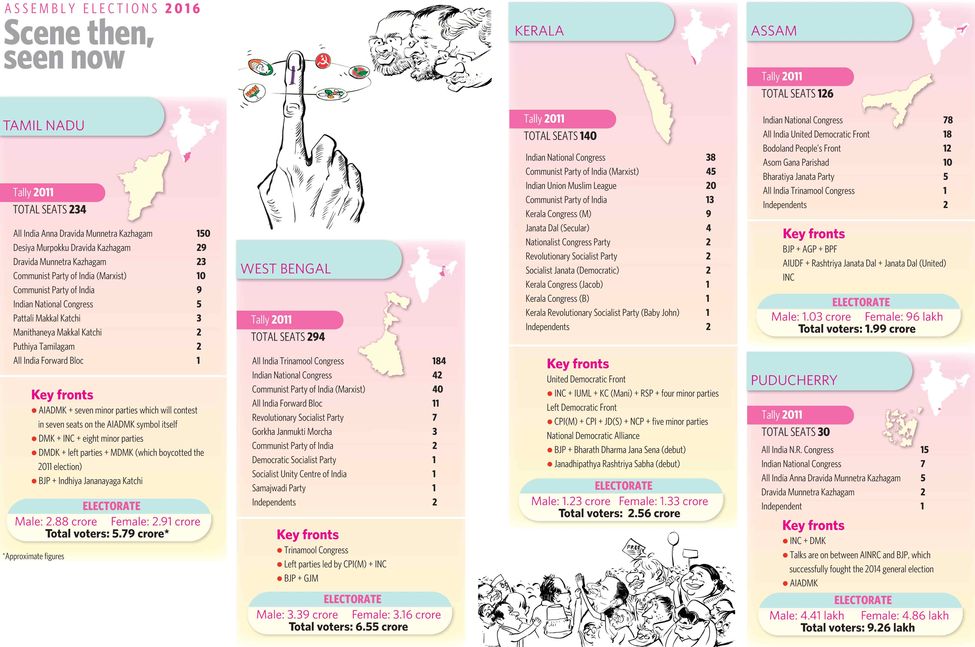

The odd locations from where fronts and non-fronts have bloomed have big implications for all parties, especially the ruling BJP. Though it had won just 10 of 116 Lok Sabha seats in Assam, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, West Bengal and Puducherry, and does not have a huge presence in most of these states, the assembly elections are a test for Prime Minister Narendra Modi. It is also a challenge for the Congress, which wants to retain its base in two states and rise from a low base in two others. Once again, there is a debate on whether Rahul Gandhi, its vice president and main campaigner, is an appealing voice. The stakes are also high for the CPI(M), whose strongholds have been demolished in the last five years. The outcome will also have a big impact on Yechury, who has taken more bold initiatives in his first year as general secretary than any of his predecessors.

For J. Jayalalithaa and Mamata, the contests are a test of their newfound confidence; both are facing the elections without any major allies. In 2011, Jayalalithaa, along with Vijayakanth's DMDK, had stormed the DMK-Congress citadel, while Mamata overthrew the communists with some help from the Congress. Now, she is asking voters to throw both the communists and the Congress into the Bay of Bengal.

However, she has to be wary of strange alliances—Nitish Kumar and Lalu Prasad, along with the Congress, beat an overconfident Modi in Bihar six months ago. The Left-Congress alliance in West Bengal was a surprise, despite the fact that the communists had given outside support to the UPA government at the Centre and the two parties have coordinated in Parliament against the Modi government.

It all started in the dusty municipal corporation office in Siliguri; the control of the hung civic body had become a prestige issue for Mamata. Pradesh Congress Committee president Adhir Ranjan Chowdhury told his party men to support a CPI(M) mayor to give Mamata a black-eye. He was joined by Gautam Deb, the CPI(M) tactician who had been the right-hand man of party veteran Jyoti Basu, but was not fully trusted by his successor Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee.

When Deb articulated the West Bengal line, which asked for bonhomie with the Congress, it horrified stalwarts like former general secretary Prakash Karat and a majority of the Polit Bureau members. They wanted to keep the Congress at a distance. Enter Yechury, who was doubly powerful as both general secretary of the party and its leader in Parliament.

If the CPI(M) succeeds in West Bengal and wrests Kerala from the Congress, Yechury's stature and power would grow in the pantheon of the opposition parties, giving the Siliguri model a broader ambience. But, if Mamata trounces her rivals, the hardliners would have a bigger say in CPI(M) policies, especially if the party fails to bag Kerala.

Modi, too, has his work cut out. In the 2014 Lok Sabha elections, he failed to do well in Tamil Nadu (two seats), West Bengal (one seat) and Kerala (none), and badly needs a dose of popular endorsement, especially after the drubbing in the Delhi and Bihar assembly elections.

Lately, Modi has changed his style of functioning a lot. He has concentrated on domestic politics, has limited foreign travel, and has vigorously advocated pro-poor and pro-farmer policies through the budget, as well as mega governmental projects. He has also changed his style of functioning as the party supremo. His twin strategy—of shedding allies and not naming chief ministerial candidates—helped the party win on its own in two small states (Jharkhand and Haryana), and emerge as the single largest party in Maharashtra, pushing long-term ally Shiv Sena into the second slot. In Haryana, Modi had dumbfounded everyone by making Manohar Lal Khattar the chief minister. Khattar was a newcomer legislator and did not belong to the dominant castes.

These decisions, along with the appointment of Amit Shah as party president, had made 2014 Modi's best year. In 2015, however, the twin strategy misfired. At first, the BJP did not name a chief ministerial candidate in Delhi but, at the last minute, paradropped Kiran Bedi into the fray. The strategy backfired so badly that only three candidates saved the BJP from a total washout in a city where it had won all seven Lok Sabha seats a few months earlier. Bihar provided to be an equally humbling lesson.

Thus, Modi and Shah paid special attention to strengthening their challenge to the ruling Congress in Assam. The party forced a split in the Congress—drawing away staunch supporters of three-term Chief Minister Tarun Gogoi—retained Asom Gana Parishad in the NDA fold, and persuaded the Bodoland People's Front, which is powerful in the tribal areas, to join the NDA. Ram Madhav, who had worked out the winning strategy in Jammu, helped in gathering views of the cadres on the acceptable chief ministerial face. Modi and Shah debated between the youthful Sports Minister Sarbananda Sonowal and ex-Congress strategist Himanta Biswa Sarma, before picking the former. Modi also decided not to focus too much on West Bengal and Tamil Nadu, where the party is bereft of major allies. In Tamil Nadu, both the DMDK and the Pattali Makkal Katchi, which were with the BJP in 2014, have since left its side.

EVER SINCE HE was BJP general secretary, Modi has had a strong fascination with Kerala. The RSS and Vishva Hindu Parishad, too, had set their sights on the southern state after an academic study had shown that disunity among the Hindu castes had affected the property and educational rights of the majority community. More than Shah, it was VHP leaders Ashok Singhal and Praveen Togadia who pushed for bringing religious-cultural organisations under one umbrella. That encouraged the SNDP, an influential socio-cultural organisation of the backward caste Ezhavas, to bring together some Hindu groups and form a party named Bharath Dharma Jana Sena. The RSS ensured that Kummanam Rajasekharan—who had tried to consolidate socio-religious groups under the Hindu Aikya Vedi—became state BJP president. However, members of these outfits have traditionally voted for either the CPI(M) or the Congress. Now, the BJP has placed its bets on the alliance with the BDJS to break the jinx and send a few members to the Kerala assembly.

For now, Modi needs a tonic—a victory in Assam and a symbolic breakthrough in Kerala—to prepare for the next round of assembly elections in 2017, which includes Uttar Pradesh, Gujarat and Punjab. A setback in both states would raise murmurs within the BJP about the Modi-Shah team. Modi would also have to face an aggressive opposition, especially as regional parties thrive when the party ruling at the Centre is weaker.

The Congress, meanwhile, is striving hard to deny Modi a victory. It has put all its Assamese eggs into the Gogoi basket, despite the severe dissidence he has faced and overcome in the past two years. Also, like Sheila Dikshit in Delhi, Gogoi has completed three runs as chief minister, but, notably, the former lost in her fourth foray. Gogoi, however, insists he is no Dikshit and has overcome strong suggestions from the Congress high command, as well as from well wishers like Bihar Chief Minister Nitish Kumar, that the Congress should have a seat-sharing arrangement with the All India United Democratic Front, the regional Muslim party which is the second largest force in the outgoing assembly. Gogoi apparently felt that sharing seats would have led to communal polarisation and thus helped the BJP. He convinced Congress president Sonia Gandhi that the party would fared better by going it alone.

Another Congress chief minister who faced and overcame turbulence within his party is Oommen Chandy, a veteran of many battles with the proverbial nine lives. He overcame strong pressure from state party president V.M. Sudheeran to remove Chandy loyalists from the candidates list. Though he has had a roller-coaster term—he implemented major development projects, but has been the plagued by scandals and scams involving himself and his colleagues—he has kept the United Democratic Front together. There has been a change of guard for the CPI(M) at the state level, but the party is yet to define the role of rebellious but popular leader V.S. Achuthanandan after the elections.

In the neighbouring state, Jayalalithaa is unperturbed that she has no allies. The chief minister has emerged stronger after a tumultuous term, during which she was convicted and imprisoned on corruption charges, was acquitted, took back the chief minister's chair, and led the AIADMK to a splendid Lok Sabha victory. Her opponents are scattered, and the index of opposition unity is low. While her long-term rival DMK has only a weakened Congress as its ally, a strange third front, which is a mixture of communist ideology, backward identity and cinematic popularity, is trying to make maverick actor Vijayakanth the chief ministerial alternative to Jayalalithaa and DMK's M. Karunanidhi.

In Puducherry, outgoing Chief Minister N. Rangaswamy faces an uphill task as the DMK-Congress alliance and the AIADMK pose problems.

Given all the calculations, it will be interesting to see who tastes victory, especially as the campaign trails this time have featured a variety of food. While Shah cemented ties with allies in Assam and Kerala by offering Gujarati sweets, Congress and communist leaders preferred endless cups of tea in their negotiations in West Bengal. The leaders who rode in the Tempo Traveller offered Vaiko's favourite snack—bread omelette. The question is, come May 19, who will eat the sweets and who will have egg on their faces?

WITH INPUTS FROM LAKSHMI SUBRAMANIAN, RABI BANERJEE, JOMY THOMAS AND V.V. BINU