Julia Cortez was having lunch when she heard the gunshots that killed her appetite. The events of the day in the impoverished village of La Higuera, in the Andes mountain ranges of Bolivia, had been so exciting for the 19-year-old trainee teacher that her mother had to force her to eat.

Her school, an apology for one with its adobe walls and tiled roof, has been holding an important prisoner since the previous afternoon. Earlier in the day, on her mother’s orders, Julia had carried peanut soup for the prisoner. He was sitting on the floor with his back to the wall, his hands tied behind him with rags. His badly injured right leg was bleeding and he looked to be in agony. When he lifted his face and looked at her, his gaze struck the girl like lightning. Despite his shabby and worn out clothes, she told herself, he was handsome. He had the soup, smiled at her, and said it was the best he had in the past many months. He said he would remember the village and do something to improve the life of the peasants if he got out alive.

On hearing the gunshots, she threw away her plate and rushed to the school. It was past 1pm on October 9, 1967. The soldiers who had been milling around the school had moved out. She looked inside, and saw him sprawled on the floor in a pool of blood. His hands were spread and his eyes half open. Or half closed.

Those eyes.

Felix Ismael Rodriguez, the Cuban tasked by the CIA to coordinate intelligence inputs, had earlier looked into those eyes and felt a sense of admiration for the man he had been trying to track down since June 1967. Rodriguez’s father had been a senior official in the Fulgencio Batista regime of Cuba, and his family was hounded after Fidel Castro came to power on January 1, 1959. Many of his relatives were killed, and the man who stood before him had personally led the executions.

Rodriguez had also been in the CIA-trained Brigade 2506, which was involved in the Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba in April 1961, a spectacular failure thanks partly to US reluctance to give air support to the Cuban volunteers. Rodriguez then sought sanctuary in an embassy and returned to the US. The failure only stoked the embers of anger that had made him attempt the daredevil mission.

Yet, face to face with the man, he found the anger dissipating. “I felt sorry for him,” Rodriguez would recall years later in an interview with newsmax.com. “He looked like a beggar.” That is what life in the ravines with very little food and medicines can do to you. Apparently, the man had given away his boots to a comrade who needed it more. “He had pieces of leather tied to his feet,” Rodriguez recalled. “It was a tremendous shock, remembering the images when he visited the Soviet Union and China, and then seeing this man the way he looked at this point in time.”

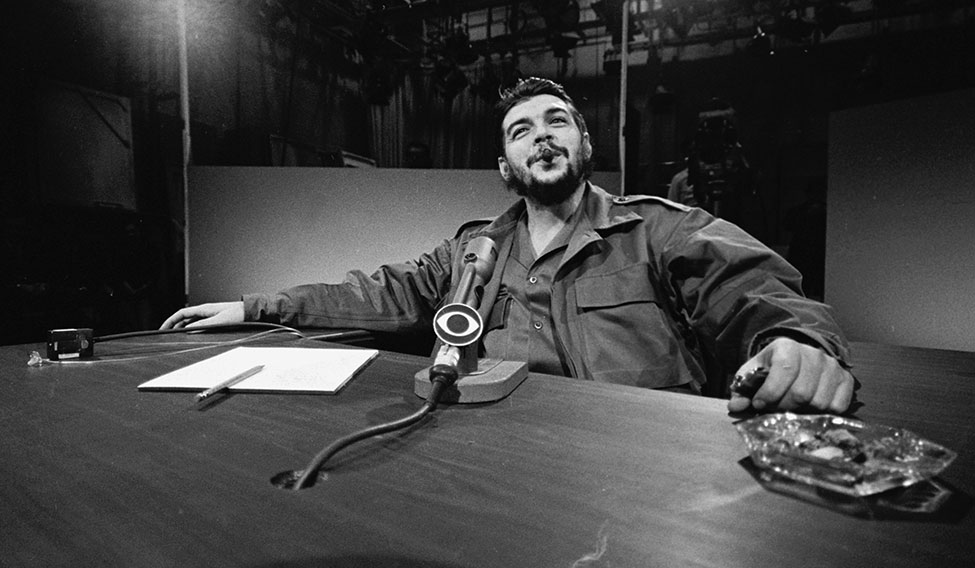

Ernesto Guevara de la Serna, known the world over as Che Guevara, had that effect on you. Especially if you had been following the career of the asthmatic Argentine physician during his days in Cuba—one who fought alongside Fidel and Raul Castro, one who visited world statesmen and addressed the UN. But, for Sergeant Mario Terán of the Bolivian army, Che was a foreign militant who had entered his country and killed his colleagues before he was trapped in El Churo ravine on October 8. Terán, 27, wanted revenge, and he was one of the three who volunteered to kill Che when Rodriguez, who was posing as a captain of the Bolivian army to hide the American presence in the direct operation, sought one. Some accounts say an inebriated Terán entered the school, only to step out to gather courage. When he entered a second time, Che stood up and looked into his assassin’s eyes and uttered his famous last words, “Shoot, coward, you are only killing a man.” (The Bolivian army version of Che’s last words is: “I am Che. Don’t kill me. I have failed.”) In two bursts, Terán pumped nine bullets into Che, from chest down, so as to make it appear that he had died in an encounter, which the René Barrientos government wanted the world to believe. He also took Che’s pipe as a souvenir.

On the memory trail- The Señor de Malta Hospital in Vallegrande, where Che’s body was autopsied and prepared for burial | Lukose Mathew

On the memory trail- The Señor de Malta Hospital in Vallegrande, where Che’s body was autopsied and prepared for burial | Lukose Mathew

Rodriguez had earlier received a call on the field telephone. It was from the military headquarters in La Paz, and it sealed Che’s fate. Rodriguez was given a pre-arranged coded message: 500, followed by 600. The number 500 meant Che Guevara, and 600, execute. A hundred more, and Rodriguez would have been a relieved man, for 700 was the code to keep Che alive. Rodriguez had clear instructions from the CIA to keep Che alive for questioning, while the Barrientos government wanted him dead. Left with very little room to manoeuvre after the Bolivian authorities turned down his arguments to keep Che alive, he decided to implement what La Paz wanted. Even as he walked into the room where Che was held, he heard shots in the adjacent room where the guerrilla Simon Cuba alias Willy was dumped. With that, the mood changed and Che knew what was coming.

“He turned white,” Rodriguez recalled on Che’s 46th death anniversary. “And said, ‘It is better this way. I should never have been captured alive.’” By then news had spread that Che had died of combat wounds. A woman told Rodriguez that radio channels have been reporting the death.

Rodriguez had been told to deliver Che’s body by 2pm, so that it could be taken to the Señor de Malta Hospital in Vallegrande, 70km from La Higuera, before dusk. He quickly sought volunteers. Terán was given the job at 1pm, and 20 minutes later, his bullets felled Che, and Julia was jolted out of her lunch.

At 2pm, a helicopter from Vallegrande landed in La Higuera. The body was bundled up and strapped on to the helicopter’s landing skids. And La Higuera bid farewell to the man who wanted to change its fortunes.

Guerrilla becomes saint- Che’s bust at La Higuera’s main square | Lukose Mathew

Guerrilla becomes saint- Che’s bust at La Higuera’s main square | Lukose Mathew

When the helicopter landed at the airfield outside Vallegrande late in the afternoon, a crowd had gathered. Also present was the chief of the Bolivian armed forces, General Alfredo Ovando Candía. As the residents and the media jostled to catch a glimpse of Che, soldiers pushed them back. Rodriguez, in his debriefing, claimed that he had quietly slipped away after the helicopter landed, but Björn Kumm, writing for the New Republic magazine in November 1967, did not agree with it. Kumm wrote that Rodriguez was very much around when a waiting car took the body to the hospital’s morgue, on a small hill, by 5.30pm. There, Dr Moises Abraham Baptista and his deputy José Martinez Cazo certified that the cause of death was “multiple bullet wounds in the thorax and extremities”. THE WEEK has a copy of the autopsy report which was part of the CIA communique sent from Bolivia to the US.

Baptista and Cazo performed the autopsy, and wrote thus in their report, signed on October 10: “... white race, approximately 1.73cm in height, brown curly hair, heavy curly beard and moustache, heavy eyebrows, straight nose, thin lips, mouth open, teeth in good order with nicotine stains, lower left premolar floating, light blue eyes, regular physique, scar along almost left side of back.” Their general examination showed nine bullet wounds, with three egresses.

Kumm had his first glimpse of Che when the two doctors and eight assistants, including a nun in whites, were preparing Che’s body. They injected formalin into the body to embalm it, with a soldier holding aloft the vessel containing the liquid. The soldiers, Kumm noted, were jubilant and Rodriguez, dressed in a T-shirt and carrying a machine gun, was leading the operation. He saw to it that fingerprints were taken, and chided the soldiers whose celebrations apparently disturbed the doctors. Kumm inched closer, and peered into the face of the poster boy of revolution. To his mind came a poster he had seen in La Paz in September, which had a picture of Che from Paris Match magazine. Stretched out on a sofa, Che looked like a model. The body in front of him did not resemble the one in the poster. It was slimmer and the hair was long and matted.

His body at the hospital’s laundry. The bodies of other slain guerrillas can be seen dumped on the ground | AFP

His body at the hospital’s laundry. The bodies of other slain guerrillas can be seen dumped on the ground | AFP

The soldiers deliberated on the necessity of convincing the world, and Fidel, that they had indeed killed Che. Rodriguez took fingerprints to convince his bosses. Kumm had no doubt it was Che. “The forehead,” he writes, “those very heavy, almost swollen lobes above the eyebrows.... If this was not Che, it was his twin brother.” The Bolivians suggested they cut off the head as proof, but better sense prevailed and it was decided to cut off the hands for the team of Argentine experts who were on the way.

A death mask was made, and in the process much of the skin and eyebrows got stuck on it. Che’s hair and beard were trimmed, and a clean dress was brought. The trousers fitted him nicely, but the jacket could not be put on as stiffness had set in. René Cadima, the local photographer, took some pictures that would make him famous. The fallen leader was laid out Christ-like on the washstand in the laundry room behind the hospital. The body remained there for 24 hours, on display for the local people and journalists. The Bolivians were basking in the glory of their achievement, even though the body had started decomposing. The time had come to take a decision on what to do with the body. The Bolivians did not want Che’s burial place to become a site of ‘pilgrimage’. The man in charge of the burial was CIA officer Gustavo Villoldo, another Cuban who was part of the Bay of Pigs invasion. Che had tormented his father, a car dealer, so much that he killed himself. Villoldo took the bodies of Che and other guerrillas to the airstrip at 2am on October 11. A six-foot deep pit was dug with a bulldozer, and the bodies of seven guerrillas were dumped in two batches.

On October 14, two fingerprint experts and a handwriting expert of the Argentine Federal Police arrived at the military headquarters in La Paz. They were shown the container that had Che’s hands. The fingerprint experts tried the Juan Vucetich system followed in Argentina (making papillary sketches of the fingers), but the formalin had caused the fingertips to wrinkle, making tracing impossible. They then took the impressions on polyethylene sheets and on pieces of latex, to be sent to the identification department of the Argentine police.

The experts compared the fingerprints with those on Che’s identity record with them and found them to be same. They were then cross-checked with the prints taken at Vallegrande. They also matched. According to a statement signed by the experts, they checked his “Bolivian Diary”, the entries starting with November 7, 1966, and ending with October 7, 1967, a day before Che was captured, and found that the handwriting matched with that of Che’s. Two days later, the Argentine embassy in La Paz confirmed that the samples taken from Bolivia matched with what they had on their records.

Although Che became part of revolutionary lore, the world was ignorant about his burial site. Those who knew did not talk, until 28 years later when journalist Jon Lee Anderson, while researching for his 800-page definitive biography of Che, met Mario Vargas Salinas, a former officer of the Bolivian army. While being interviewed, Salinas revealed how Che’s body was dumped with the bodies of the other guerrillas beneath the airstrip at Vallegrande.

A mad scramble to unearth the remains followed. For two years, forensic experts from Cuba toiled in vain. Finally, they found the remains in 1997 and took them to Santa Clara in Cuba, where Fidel erected a mausoleum for the revolutionary who had said a guerrilla had no resting place.

The legend grows- The tree planted by Che’s daughter Aleida Guevara at the airstrip in Vallegrande, where Che’s body was found in 1997 | Lukose Mathew

The legend grows- The tree planted by Che’s daughter Aleida Guevara at the airstrip in Vallegrande, where Che’s body was found in 1997 | Lukose Mathew

Che’s mission in Bolivia was doomed from the beginning, thanks to the noncooperation of the Bolivian communist party and the public. The Soviet Union was also unhappy. Soviet President Leonid Brezhnev dispatched his premier Alexei Kosygin to Havana in June 1967 to take up the matter with Fidel. According to a CIA report, Fidel explained his position to Kosygin and the Cubans considered the visit productive.

Che had been a thorn in USSR-Cuba relations since Fidel came to power. As a key functionary in the government, Che favoured centralisation and leaned towards the Chinese model of development pioneered by Chairman Mao. A CIA memorandum dated October 18, 1965, noted that Che was a marked man from the time he positioned himself against the practical policies recommended by the Soviet Union regarding Cuba’s economic development.

As minister for industry, Che insisted on accelerated industrialisation. He wanted to move away from Cuba’s overdependence on sugar and advocated diversification in the agricultural sector. However, by 1963, Che’s industrialisation plan was scaled down to allocate more resources to sugar production.

Between Che and his dream of industrialisation and centralisation stood Professor Charles Bettelheim (formerly associated with Jawaharlal Nehru), who had come to Cuba on Che’s invitation for a grand debate on socialist economics. A French Marxian economist, he had Fidel’s ear. In 1963, he convinced Fidel that the decade that followed should be of advancement in agriculture and that authority should be decentralised. A six-year sugar plan was subsequently announced and tentative steps were taken to give greater autonomy to two towns. But Che was still a force to reckon with and the fight on centralisation continued.

Che wanted the Cuban experiment to be exported to Latin America, and even Africa. In December 1964, he left for a three-month trip of the UN, Africa and China. In his absence, Fidel promoted further sugar production. In February in Cairo, Che criticised the path Cuba followed, which he observed was a copy of the Moscow model of economics.

Che returned to Havana on March 13, and was received by Fidel. By March 20, he slipped out of the public space. Three months later, the axe fell on his associates. In mid-June, National Bank president Salvador Vilaseca was transferred as rector of Havana University. On October 1, when the central committee of the communist party was reconstituted, three ministers close to Che found themselves out in the cold. Che, by then, was far away in Congo, taking part in another doomed revolution.

The following day, Fidel read out a letter from Che, which was meant to be made public in the event of his death. Dated April 1, 1965, it recalled their first meeting in Mexico City. “I feel that I have fulfilled the part of my duty that tied me to the Cuban revolution in its territory, and I say farewell to you, to the comrades, to your people, who now are mine,” Che wrote. “I formally resign my positions in the leadership of the party, my post as minister, my rank of commander and my Cuban citizenship. Nothing legal binds me to Cuba. The only ties are of another nature—those that cannot be broken as can appointments to posts.” Che was effusive in his praise of Fidel’s leadership qualities while recalling the days they fought against the Batista regime. When Fidel made the letter public, the doors of Cuba closed on Che officially, but their relationship remained as warm as ever.

According to Che’s biographer Jorge Castañeda, at their last meeting just before Che left for Bolivia, it was Fidel who did all the talking. Che had originally wanted to go back to Argentina and start a revolution there, but Fidel, knowing that it would be suicidal, had suggested Bolivia and had negotiated with the Communist Party of Bolivia, which had offered all help. Though Fidel knew about party leader Mario Monje’s wavering stand, he would not have known the extent to which the party would go to sabotage the mission. In the end, the Bolivian mission proved as suicidal as the Argentine one Che had in mind would have been.

“The people were generally afraid and had no sympathy for the guerrillas,” Milan Sime Martinic, former entertainment editor of the Las Vegas Sun and grandnephew of Barrientos, told THE WEEK. “We were at that time living in Cochabamba, having left La Paz in February 1967. There was talk of Che and the Cubans invading Cochabamba. I was scared.” Milan was six at the time, and he remembers government propaganda on radio that the guerrillas would come, kill people and take away the cattle. Around the time, General Candía confirmed Che’s presence in Bolivia and the US sent its Green Berets under Major Ralph ‘Pappy’ Shelton to train the Bolivian Rangers. Che had divided his meagre force in vanguard, rearguard and central columns, and the three lost touch with each other.

The months of August and September were the worst for the rebels, as they were constantly on the move, pursued by the army. They were without supplies, and Che’s health worsened. On October 7, the day Che made his last entry in the diary, a potato farmer reported seeing the guerrillas at the Churo ravine. The next morning, they were located by the army, which began firing at them from the heights. Che and his small band fought back, but the odds and the numbers were against them. Che and two of his comrades were caught and taken to the school in La Higuera.

The operation had failed, and the doctor had to die.