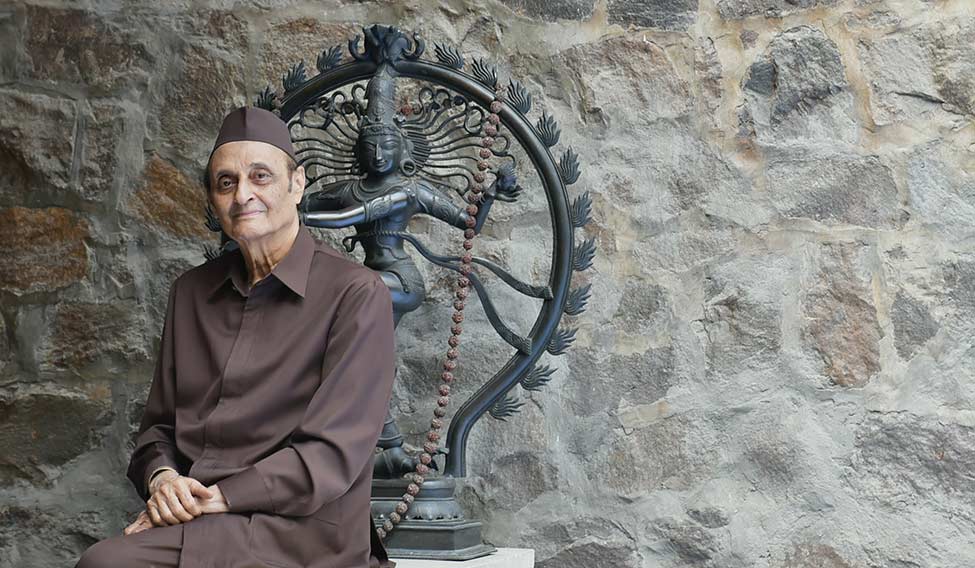

Dr Karan Singh’s house at Chanakyapuri, Delhi’s diplomatic enclave, looks unassuming from outside. But, inside, it is the abode of the son of the erstwhile ruler of Jammu and Kashmir. Stuffed with antique statues (especially those of Natraj), paintings, artifacts and books, the house is a piece of history in itself. “I built this house in 1960 and Panditji [Jawaharlal Nehru] had come for the housewarming,” recalls the 86-year-old Congress leader, dressed in a dark brown shirt, trousers and Nehru cap. “He was very fond of me and used to call me ‘Tiger’.”

Singh considered him his idol, “the iconic figure for our generation”. Their first meeting was a fleeting one, when Nehru visited Maharaja Hari Singh, Karan Singh’s father. But the moment stayed with the young prince. “As he entered the room, I was struck by two things, the agility with which he moved and that unforgettable smile—pensive, yet intensely human. I was too overwhelmed to say anything very intelligent, and simply asked him to autograph my copy of his An Autobiography,” writes the Rajya Sabha member in his autobiography.

Nehru’s books—An Autobiography and Discovery of India—gave Singh a new awareness and strengthened his growing aversion to feudalism. “I grew up greatly influenced by the nationalism that Nehru represented,” he says. In fact, his influence was so much that even though Singh’s father and Nehru disliked each other, Singh decided to go with the prime minister. “My father was very angry, but I don’t regret that at all,” says Singh, who had dreamt of becoming a “perfect ruler” during his schooldays, but never hesitated to accept democracy.

“I realised clearly that the old feudal structure was on the verge of collapse, and that, in any case, my father’s life was not for me. What the alternative was I did not know, but inwardly I was ready for the change. There was a great euphoria among the people of my generation to be part of the new India.”

The Indian republic is a reality today not only because of our freedom fighters, but also because scores of royals across India accepted democracy as an idea whose time had come. Singh is a shining example. “When my father died in April 1961, technically I became the maharaja, but I made a statement saying that I am not going to use the title,” he said.

Singh continues: “My father belonged to the feudal order and, with all his intelligence and ability, was not able to accept the new dispensation and swallow the populist policies of the then mass leader Sheikh Abdullah.” Citing an example of his father’s feudal nature, he says the king would be jolly if he had landed a good catch after shikar. If not, he would be in a terrible mood. That meant some unfortunate employee losing his job in the middle of the night.

“Even my mother [Maharani Tara Devi], with whom I had such close emotional links, seemed to be on the verge of psychological collapse,” Singh writes. “Her position was excruciatingly difficult—on the one hand was her loyalty to my father despite their temperamental differences, and on the other was her devotion to her only child.”

Karan Singh | Aayush Goel

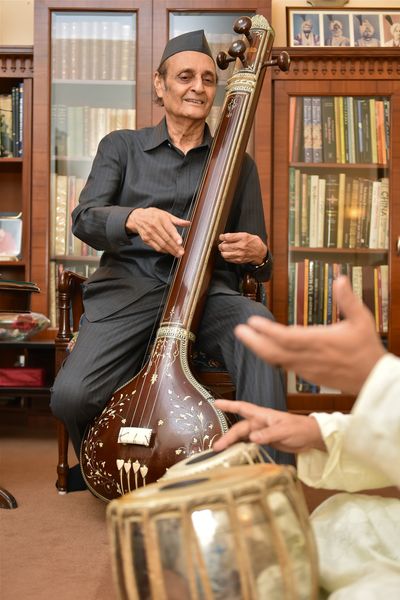

Karan Singh | Aayush Goel

Social consciousness doesn’t come easily to a prince who lives in a self-contained world where servants are taken for granted. The question of why someone should be the ruler and others ruled is never thought of, let alone asked.

But, Singh was introduced early to the concept of distributive justice, thanks to his parents. Because of his authoritative father, he grew to dislike the feudal system. And, he loved the generosity of his mother—the maharaja’s fourth wife, daughter of a poor family from a remote village in the Kangra district of old Punjab.

Besides that, what made the crucial transition from feudal to democratic life easy were his four “unpleasant” years in Doon School, Dehradun. “There, I had to do everything myself and did not have servants hanging around. I had to clean my own clothes, make my own bed, polish my shoes and be content with the pocket money of five rupees a month,” he says. “It all moulded my conscience to a more democratic and egalitarian society.”

Apart from this, Singh says, a yearlong trip to the US in December 1947—two months after his father had signed the Instrument of Accession with the Union of India—gave him an opportunity to absorb a much freer and democratic atmosphere. He was there to treat a hip problem. “My stint in America influenced my mind and my conscience because I was away from the feudal order and tension in Kashmir,” says Singh, who recollects being in the same house, but in a different room, when the accession document was signed.

“I was only lying on the bed there, but my body and mind grew,” says Singh, who recalls how a TV set in his hospital room had become a topic of conversation among the hospital staff, as it was a rarity and luxury then.

After returning to India in February 1949, after his father went into exile, Singh was made the Regent (1949-52), Sadr-i-Riyasat (1952-65) and eventually governor of the state (1965-67). “Essentially, it was the same job with different nomenclature,” he quips. In 1967, he became the youngest Union cabinet minister, and went on to handle several high-profile portfolios over the years. Having lectured worldwide on Indian culture and philosophy, Singh’s tastes are eclectic, in keeping with his exposure. Very spiritual, he sings classical music and is addicted to rock music.

Singh clarifies that although he disagreed ideologically with his father, he credits him fully for preparing him for life. “My father had laid down a strict discipline for me,” he says. “From the age of six, I lived separately [in Karan Mahal] with two companions. I would visit my mother thrice a week and my father once [at Gulab Bhawan]. As I was the only son, he didn’t want me to be spoilt.” It was for the same reason that the father picked Doon School, which was considered quite progressive then, over Mayo College, where most of the elite studied.

While Karan Mahal in Srinagar, Hari Niwas in Jammu and Taragarh Palace in Kangra continue to be with Singh, Gulab Bhawan in Srinagar is now owned by The Lalit Hotels. The Amar Mahal in Jammu is now a museum housing the royal collection of books, photographs and Kangra paintings.

Ask him whether he misses the royal life, and he recites a couplet by poet Omar Khayyam:

“The moving finger writes; and, having writ, moves on: nor all thy piety nor wit shall lure it back to cancel half a line, nor all thy tears wash out a word of it.”

“It is gone. And you have to move on,” says Singh, who has authored 20 books and loves poetry. “I never live in the past. I never look back in anger or regret. It never helps. That is why in all these years, I have been able to grow inwardly and make some kind of contribution to India’s public life.”

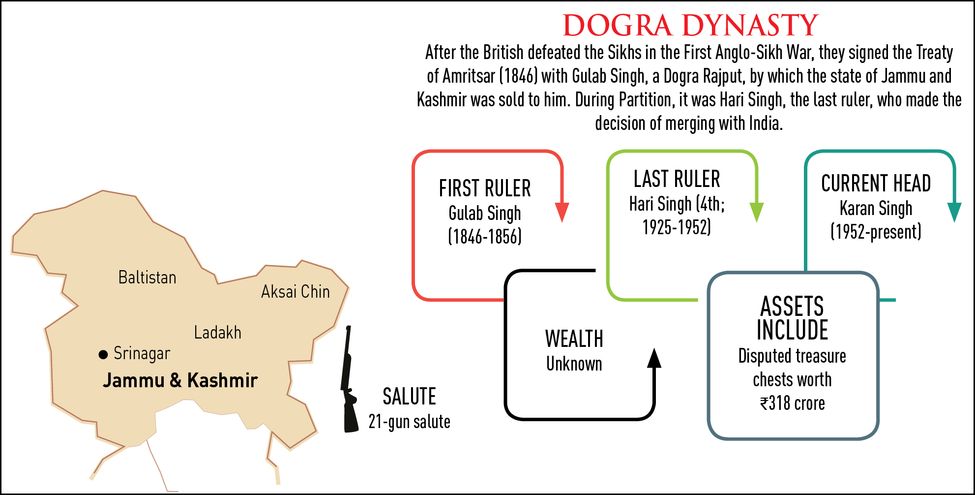

While Singh has happily renounced royalty, he holds his roots dear. “We have a very rich past,” he says. “Our family, the Dogras, was the one which built the state of Jammu and Kashmir, conquered Ladakh and we have a done great deal for the country.

“Also, we run over a 100 temples in Jammu and Kashmir. My sons keep going back and forth. They are more interested in keeping touch with the old traditions. So, we have religious processions on Dussehra and Vijayadashmi. The sons are little more attracted to the past than I am, perhaps, because they haven’t seen it.”

In March 1950, Singh married Yasho Rajya Lakshmi from the royal family of Nepal. She was 13, and he 19. They literally grew up together, and were inseperable until her death in May 2009. Singh fondly called her Asha and says she had deep interest in politics and her contribution in his political life had been immense. “She had an independent mind and was a great judge of people,” he adds.

The couple’s three children have taken to public life smoothly, like their parents. Both their sons are members of the Jammu and Kashmir legislative council. Eldest son Vikramaditya Singh is a leader of the Peoples Democratic Party, and is married to Chitrangada Singh—sister of former Union minister Jyotiraditya Scindia—of the Gwalior royal family. Second son Ajatshatru is with the BJP, and is married to Ritu Singh. Daughter Jyotsna Singh and husband Dhirendra Singh Chauhan are active in preserving Kashmiri art and literature. “We have a completely democratic family,” laughs Singh, who has six grandchildren, two each from every child.

Although the father and sons have lots of political interaction, arguments over ideological differences are rare. “I share a very creative relationship with my sons, unlike my relationship with my father,” Singh says.

In what ways has democracy and its meaning changed in all these years? “The major change has been that the submerged classes have risen through the democratic system,” Singh says. “The Scheduled Castes and Tribes, which generally had very little say, came up. That is why you had the phenomenon of Mayawati, Kanshiram or Mulayam Singh Yadav.”

“So, in some ways politics has become more egalitarian than what it was. In other ways, it has become more corrupt. The whole political system lends itself to corruption and the huge expenditure on elections forces people. That is one of the grave dangers we are facing.”

“The youth take the democracy for granted. There is inadequate realisation that if you have to nurture democracy, you have to follow some guidelines.”