It's a simple face. The eyes slope upwards from the broad bridge of the nose, their outer ends crinkling into a delicate network of crow's feet every time their possessor breaks into a smile, which is often. Wisps of grey are beginning to show on the otherwise jet black hair that frame the cream complexion. The juice of tamul (uncured betel nut) and pan (betel leaf) stain evenly set teeth. The habit is recently acquired, but its imprint already very clear. On the other hand, the stamp of another, much longer and influential aspect of her life, is barely there. For a woman who has reportedly survived nearly four decades all by herself in the wilderness of the rainforest, the face gives away almost nothing of those years, or the events that filled them.

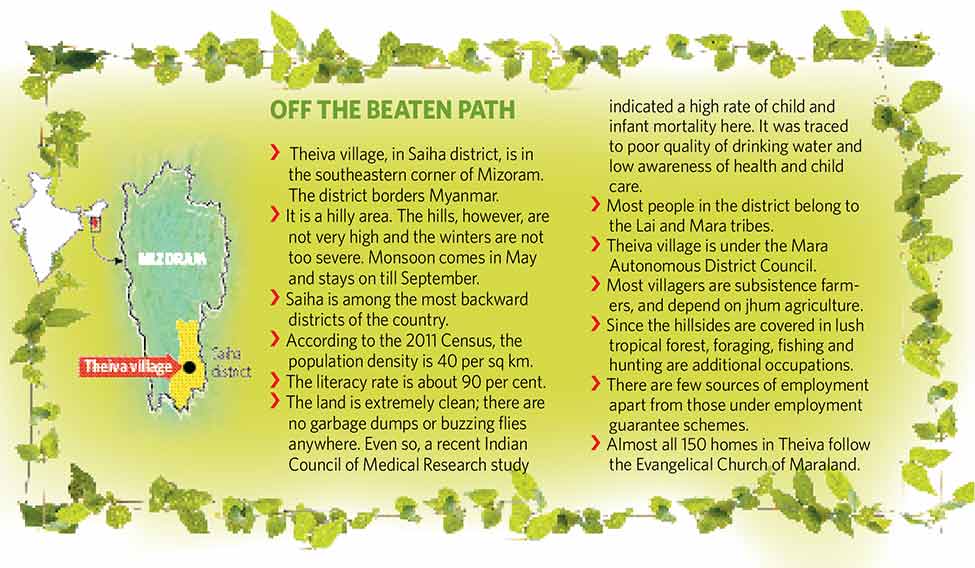

Ng Chhaidy is the girl who came back, fairy-tale style, from the forest where she had disappeared as a four-year-old a very long time ago. The year was 1974. Later on, people would remember it as the year of the Smiling Buddha, when India conducted its first nuclear test in Pokhran, Rajasthan. Others would say it was the year of the last smallpox epidemic, which claimed 15,000 lives. In a remote village, Theiva, in Mizoram's southeastern district of Saiha, it was the year a little girl was swallowed by the forest (back then, Mizoram was a Union territory). Her disappearance went without a ripple outside her small community and, even among them, was eventually forgotten.

Chhaidy's homecoming in 2012 was, however, a momentous event. People from distant villages and even towns flocked to Theiva to see the Mowgli woman. “There were over a thousand people here,” say the villagers. Local government officials, the panchayat and church community put up a felicitation function in her honour. What the awaiting crowd anticipated was certainly not what it witnessed—instead of a savage looking person, they beheld a well-groomed, petite woman draped in a Mizo wrap skirt and top. She walked into a village she had no recollection of, to be with a family she had no association with. For the record, she wasn't coming straight out of the jungle; she had spent five years with a family across the border, in a village called Aru in Myanmar, and was now being sent to her birth family. The event was momentous enough for it to be reported across the world, from the United Kingdom to China.

And then, poof. News has a way of being flicked off the spotlight with the same abruptness that brings it centrestage. Within weeks, Chhaidy was news no more, other believe-it-or-not snippets had replaced her. Now, three and a half years later, her name doesn't ring a bell with most, even in her own state. “Yes, we had heard about such a story,” say people in Aizawl. “Is she for real? Is she still there?” they then muse, disinterestedly.

Yes, Chhaidy is very much there, ensconced in the warmth of a family that regards her as a manna from the heavens and embraced by a community that regards her as a miracle of the Lord. There's barely a trace of the wild about her as she mimics the civilised behaviour of those around her. She dresses with care, attends church gatherings and helps in the fields and with housework. But she lives in a world of silence, in which only a skeletal vocabulary has managed to establish itself. So while she smiles charmingly or sits with rapt attention when others are having a conversation, what goes on in her mind, no one knows. And perhaps, may never know.

Chhaidy with her mother | Salil Bera

Chhaidy with her mother | Salil Bera

Chhaidy has received no professional help to deal with what must have been several mental upheavals in her life. Her village, Theiva, is a 14-hour drive from the capital, Aizawl, through a battered highway on which even locals are reluctant to ply their vehicles. The place gets completely cut off during the monsoon, which lasts half the year.

In a state that has a population of just around 11 lakh, there aren't many, actually it appears no one, who is interested in researching the psyche of a feral child. Mizoram doesn't even have a medical college, the closest being in Guwahati, Assam, several hundred kilometres away. Mizoram is cut off from the outside world by a people who fiercely guard their uniqueness and don't want their ethnicity to dissolve in India’s homogenous brew. Outsiders need an inner line permit to enter and stay for a limited period.

Luckily for her, Chhaidy seems to have adjusted remarkably well to her new lifestyle. Emotionally, she is a child of not more than 12, says her mother, V. Ngolah. Impromptu hugs and kisses are what she gives, and demands. She gets that among her people.

But professional intervention would have been useful. For instance, she could have picked up more language skills than the dozen words she can articulate. Perhaps her emotional and psychological growth could have been brought closer to her chronological age, says Suman Verma, former head of human development and family relations at Chandigarh's Government Home Science College and member of several international projects on adolescent behaviour.

Also, she could have provided a mine of information for researchers. There are not more than a handful of reported cases of feral children returning to the human fold. And, those few haven't been authenticated. In recent times, there has been only one other case (see box on page). Thus, an immense research opportunity in the field of human behaviour remains untapped.

Chhaidy's fantastic story began on a fine day in May. Four-year-old Chhaidy, and her same-aged cousin, Beirakhu, trotted behind their grandmother to the forest fringing their village.

Despite their tender age, the excursion was not a novelty to the cousins. They were Maras, a tribe that lives in southeastern Mizoram, close to the Myanmarese border. Their villages are carved out by clearing rainforest, but the fecund jungle closes in with phenomenal speed. This is not necessarily bad for the Maras, whose livelihood is intricately entwined with the forest.

While jhum agriculture, or slash and burn cultivation, forms the mainstay of the Mara economy, the forest supplements their livelihood in several other ways. They hunt these woods, fish the streams and forage the undergrowth to bring to the dinner plate all the Mara delicacies that lift the staple of rice into a full and fragrant meal.

Hunting and fishing are a man's job, foraging is for women and children. That is exactly what this family was doing that afternoon, 41 years ago. As the old woman moved on, sickle in hand, dropping edible ferns and tubers into her basket, she didn't realise the children were no longer with her. At some point during her exertions, when she must have paused to straighten her back, granny noticed the still silence, with no childish prattle to fill the vacuum left by the resting cicada. She went back to her work. Kids living on the edge of the forest know their way back home. She worked till her baskets were full and then returned to the village. There, she met some neighbours and spent the rest of the afternoon in idle chit chat.

But when the cowdust hour approached and Theiva's people returned home from field and forest, two young mothers found their toddlers missing. They began asking around with neighbours, and it was only after night descended that they realised the children had been left behind in the forest.

After five days of combing the edges of the forest, a search team found Beirakhu on a rock beside a mountain stream, faint from hunger and fatigue. The girl, however, was not there.

For more images: Return of the Mowgli woman

A 44-year-old householder today, Beirakhu has almost no memory of that eventful phase of his childhood. “All I remember is that I was very hungry,” he says, desperately trying to pull out another strand of memory. Village lore, however, is that the toddler told them they followed an old woman who seemed like their grandmother but turned out to be someone else. She led them to her house in the forest and fed them, the boy recounted. So the villagers returned to the forest in search of this mystery woman, finding trace of neither her nor her house. Was she the creation of a child's mind that was delirious with hunger, fear and fatigue?

Villagers, however, still choose to believe that the boy's version of the Hansel and Gretel tale was true. According to them, the woman was an evil spirit. Although every member of this 150-household cluster is Christian, the faith was introduced only about a hundred years ago by missionaries. Here, animistic beliefs cohabit with the gospel truth. The deep, dark jungle would anyway sway even the most rational man.

While there aren't too many large predators like leopards or tigers, the jungle has its population of wildcats, wolves and bears. But, when animals kill humans, they leave behind some evidence—a scrap of frock, a lock of hair and uneaten bones. The search parties concluded that if not taken by the wild, she had been whisked off by the spirits. Either way, she was lost to them.

“Among Maras, the custom is to wait for four years before declaring a missing person dead. In my heart, I waited for ten years; then, I, too, gave up hope,” says Ngolah. Heavy into her second pregnancy when Chhaidy disappeared, she gave birth to a son a month later, and got engrossed with the demands of motherhood.

Chhaidy, meanwhile, almost became part of legend. Sometimes, villagers would hear of passersby telling them they had seen a wild girl in the jungle. Were these travellers hallucinating, their impressionable minds having picked up the tale of a lost girl and embellishing it to a vision which scared them out of their wits? Or was it really Chhaidy? The mystery is unsolved, for Chhaidy can’t tell.

Many years, indeed decades, went by. Far, far away, in settlements on the other side of the forest, in Myanmar, a wild woman began making appearances in the early years of the new millennium. Completely naked, her nails long and gnarled and her hair a matted mass, she had been seen in the morning by farmers who went to their jhum fields. Sometimes, she appeared in a village, but would vanish before anyone could catch her.

One day, in 2007, the woman appeared in a village called Aru, a two-day trek from the border. She looked lonely, craving company, and she was unwell, too. She was wearing a shirt that wasn't worn in their parts. A devout villager extended his hand towards her, she willingly came to him and was adopted by his family, he becoming the father figure in her life. Many villages on the Myanmarese side of the border, too, are of Mara ethnicity and they have familial bonds with the Indian Maras. In fact, by an agreement between the two countries, there is free movement for residents of villages within a 15km radius on either side of the border. But the porosity of the border spreads much further. There are families in Theiva which have married into Aru homes.

“One day, a distant relative from Aru came to our village and began telling us stories about the jungle woman,” says Ngolah. “They said she looked like my husband.” Hope blossomed in withered hearts, and her husband, Khaila, whose main source of income apart from agriculture was as a casual worker in government employment guarantee projects, finally readied himself for the arduous three-day journey to Aru, along with some villagers. Chhaidy, by then, had adjusted to a domesticated, if silent, life among humans. “She beamed when she saw Khaila, addressing him as ippa (father),” recalls Ngolah. This caught Khaila off guard but warmed the cockles of his heart and he resolved to bring her back home.

Was a child woman with a limited vocabulary addressing an elderly man as ippa enough proof that she was his lost child? No, says the mother. Before Khaila left, the panchayat had already spread word across Maraland (an autonomously governed region of Mizoram) for information on anyone of her description who may have disappeared anytime over the past years. There was no missing person who fit her age and description. That she was a Mara was for sure, her ears were pierced in a style typical of the tribe.

Those were trying times for Ngolah who painfully realised that, over the decades, her little daughter's features had faded from her memory. There wasn't even a photograph with her. “But I remember she had been scalded by boiling water accidentally once. And, most importantly, she was left-handed.” The woman in Myanmar had a similar scar on her leg and she was left-handed, too. These, and the resemblance to Khaila, decided Chhaidy's fate. She was to be brought “home”. The Aru family concurred, and Chhaidy left her home of the last five years, to step into another unknown once again. She came smilingly, but was she aware how momentous this journey was? It wasn't as if anyone was consulting her about her life.

She doesn't have the language to tell others, but Chhaidy does miss her Aru family. Her “Aru ippa” visited Theiva a couple of times, and she was ecstatic to meet him. Chhaidy's emotions are untrained and her joyful reactions were so extreme that even the simple-minded family realised these visits might do more harm than good to her. They agreed it was best for her that the Aru chapter be closed forever. But is it closed in her mind, too?

Khaila died this September and the faded pictures of him aren't clear enough to show their familial resemblance. However, Chhaidy, with her light skin, looks quite different from her mother, brother and sister, all of whom are brown. While she is as slim as the others, her build is different, and at less than five feet, she is much shorter than the others.

Everybody, however, says she was daddy's girl, in looks and attachment. “She doted on him, and when he died, she wept miserably for days,” says her brother, Beiha. In fact, she started clinging to her mother only after the loss of her father. As we sit in the large living room of their house on stilts, Chhaidy tugs my arm and points to her father's picture on the wall. “Ippa,” she says, and then her face crumples up with sadness. The gloom doesn't last long, for she is of a sunny disposition. She has heard music in the distance and wants to go to the fellowship, a gathering of church members, where there will be song and dance shortly. Her mother tells her to change her clothes, and she breaks into an impromptu jig. “Give her something new, ask her to dress up, and she is very happy,” says the doting mother.

Chhaidy has learnt to boil rice and make tea and she helps with the cleaning and field work. But she will only do a chore when asked to | Salil Bera

Chhaidy has learnt to boil rice and make tea and she helps with the cleaning and field work. But she will only do a chore when asked to | Salil Bera

Chhaidy has inborn sartorial taste. She steps out in a bright green wrapper and a fitted red top, clothes she selected herself, looking like a bright flower. She walks with measured steps to the community hall, where she sits quietly as the preacher speaks, muttering alleluia when the others do. Then, the drums start and one by one, the congregation forms a circle and begins to dance. The rhythm picks up—the singing gets louder, the music more lilting and the dance more swaying. There is a trance-like atmosphere in the hall. Chhaidy joins in, clapping to the beat, mimicking the actions of others and thoroughly enjoying herself. Her dancing is not as sinuous, though. Each time she glimpses at us, she beams. She knows we are outsiders, and have a connect with her the others don’t. After the dance, she stands by the entrance, pointing at exiting women and occasionally saying, “Papei” (madam or lady).

Didn't the family need further corroboration that she was theirs? “No. we were convinced,” they say. “At this stage in my life, when Abei ippa (Holy Father) has returned our child, should we question him? My husband used to say he would die without knowing where Chhaidy went. But she returned to him. She is ours,” says Ngolah emphatically. We discuss DNA fingerprinting, and she says, “No one from the government came to test our blood. I won't do it, because I don't need more proof. But anyone who wants to run tests on us is welcome, we won't stop them. The outcome, however, will not change our belief.”

So what is it for a family to suddenly learn of another member and have to share home with her? Chhaidy lives with her mother, brother, his wife and three little nephews. “I had never met her before, but she is my sister. I'm glad she is with us,” says Beiha with simplicity, though he wishes they could communicate better. Her mother's emotions are still raw. “I used to dream of my lost girl and when I saw Chhaidy, it was difficult to connect this woman with that little toddler. And so I wish I remembered more of that little girl, but time has faded memories. As a mother, that is so frustrating. Even now, I look for traces of that girl in her.”

Equally frustrating is that they have no access to her thoughts, or know anything about what happened to her in all those years. Every local believes it is impossible to survive in the forest for so many years, and Chhaidy was only a four-year-old back then. “No, we have never heard of anything like this before. That's why we consider her a miracle. The Holy Father kept watch over her,” says T. Beivai, a leader of the Evangelical Church of Maraland. On her return, the church formally baptised her and accepted her into its fold.

So, was Chhaidy completely insulated from human company all those years? It's difficult to say. The “gibberish” she usually speaks has no resemblance to any Mizo language. Where all did her perambulations take her, did she meet people of a different community somehow, somewhere? Given that so many fairy tales are woven into her life, did any wild animals help her survive, like they did for Mowgli and Tarzan?

“This is such a fascinating story, I wish there was some neurological study on her. She would have benefited, as would have science,” says Verma. “I had once read of a child who had been reared by wolves for some years. It is possible that someone, or something, took care of Chhaidy. The human instinct for survival, however, is so tenacious that it is entirely possible she managed to adulthood by herself.”

“She gives nothing away,” says Beiha. Yet, sometimes the window to the past opens a crack. Chhaidy has good knowledge about the jungle, she knows what's edible and what isn't, and also the best places to find a particular fruit or fern. Who taught her all this? While most Maras are comfortable enough when entering the forest, they marvel at the ease with which she moves around there. “She used to run off to the forest very often initially, specially when she was in a bad mood,” says Byhnathie, the sister born two years after Chhaidy's disappearance. She has spent nights alone in the jhum hut, away from the village. Once, she was discovered the next morning at the gates of Maraland, several kilometres away. The nocturnal runs have become less frequent, as the family has learnt to gauge her mood and keeps vigil on evenings when she appears listless. What puts her in that frame remains another of those unsolved mysteries surrounding her.

For a woman who knows no fear of the dark, of loneliness, or of animals, Chhaidy is surprisingly scared of rats. She screams like a crazed woman if she sees one. She even recognises rat meat when it's cooked and will refuse to take a morsel, getting very agitated even if the bowl is kept beside her. Rodent meat is a delicacy here, specially in the winter months, when field rats, fattened on the harvest, make for a succulent meal. Is it just a natural aversion, or is there a traumatic untold story behind this reaction?

Emotionally, she is a strange mix. Independent enough to run off one moment, she is excessively in need of affection the next. Fond of children, she often picks up little children on the village street and plays with them. Yet, she refuses to share her food or trinkets with them and can fly into a rage if asked to. She is quick with modern gadgets, be it lighting the gas stove or flicking channels on the television set. Mobile sets fascinate her, as does a drive in a car, a very rare treat. We took her on a short drive, which thrilled her no end. Later that evening, she would tug at people's arms, pointing to the SUV and then moving her hands to indicate the steering wheel, a wide grin splitting her face.

The human mind is hardwired to interact with humans, explains Satish Girimaji, head of child and adolescent psychology at Bengaluru’s National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences. So, even after long separations, an individual will reach out to fellow humans. But in a person out of social environment for years, especially since the early childhood period that is crucial to development of social skill, the isolation will leave its mark.

“It’s difficult to say much without meeting her, but perhaps the woman was crying for social interaction, that’s why she began appearing near human settlements. At the same time, the jungle is her comfort zone, she will naturally seek it out,” says Girimaji. “These cases are so rare, that there is not much study in this field. Individuals may appear very different from each other, and certainly from similar fictitious characters.”

Chhaidy has learnt to boil rice and make tea, and she helps with the cleaning and field work. But she will only do a chore when asked to. She has learnt to do simple shopping, like bringing back a pack of cigarettes, but has to be given exact change. Even basic arithmetic is beyond her. An unwelcome word comes to the mind: domesticated.

She learns by observing and mimicking the actions of others and her movements and deportment have refined over the years through this self-schooling. The others haven't really given a thought to providing her with formal training or even basic education as, by and large, they accept her as she is, much like a special child.

In the realm of fiction, there is always a love interest in the lives of feral children. Tarzan had his Jane, even Mowgli, all of 11, was smitten by a village belle. But there is no Prince Charming in this jungle woman's life, not yet, at least. Within the village, she has become “best friends” with four other women, which largely means she loves to attach herself to their group and listen to them as they chat after church meetings or in the afternoons. While she isn't shy of males, she has never shown that special attraction to any one of them. She hasn't menstruated even once after coming to Theiva. “There was no medical examination done on her, so we can't tell what, or if, there is a problem,” explains S. Vabeihasa, information and publicity officer, Mara Autonomous District Council. No one even knows whether she is a virgin. “Psychiatric counselling, medical examination, formal training... why weren't they provided, you ask. Well, honestly, I don't think anyone here ever thought about these ideas so far,” he adds.

Saiha is one of the most backward districts of Mizoram. An Indian Council of Medical Research study recently pointed to the high infant mortality here, a result of poor health awareness, contaminated water supply and general poor health. It just isn't the kind of place where people would think of anything beyond basic health care.

Back in Aizawl, the state’s health and family welfare secretary, Lalmingthanga, remembers the story of Chhaidy but isn’t aware whether there has been any intervention at the district level for her welfare. He consults senior medical officers in the government at our request, all of whom concur that surviving alone for so long is next to impossible. “She may not have been entirely alone. Perhaps there was sporadic human intervention,” they suggest. But they have not met her and know little about her. The department has bigger issues to deal with. Mizoram is malaria-endemic, a problem that refuses to even come under control. Cancers of the oesophagus and stomach are unnaturally high here, and the biggest social and mental health challenge is rampant drug and alcohol abuse. The welfare of one village woman in a distant corner isn't on the radar, especially since no one has asked for it on her behalf.

In some ways, the insulation from the outer world is a blessing for Chhaidy. She lives amid a simple, devout community whose needs are basic. There is little to intimidate her. Perhaps the interest of researchers, blood tests, visit to cold and intimidating medical centres and relentless media exposure may have been a strain on her, her family and society, as has happened in the case of Rochom P’ngieng, a Cambodian woman who returned home, reportedly after 18 years in the jungle, interestingly in the same year, 2007, when Chhaidy materialised in Aru. News reports about Rochom describe the difficulty she has adjusting to society, preferring to live in the chicken coop instead of the house. Chhaidy likes the comfort of her cot.

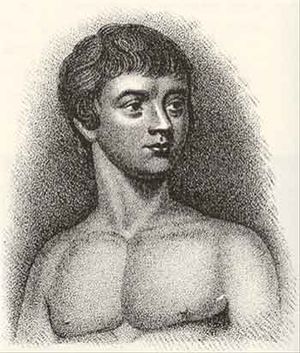

French, feral: On finding him, many scientists experimented on Victor.

French, feral: On finding him, many scientists experimented on Victor.

When her parents christened their firstborn, they hadn’t realised that they were encapsulating her life story in her name. The first syllable of her name, chhai means “to separate, see off or disappear”. The second syllable, da, means “to welcome”. As we get ready to go, Chhaidy smacks a loud kiss on my cheek, leaving traces of her pink lipstick and engulfing me in an affectionate, diminutive bear hug. She holds up two fingers in the victory sign for photographer Salil Bera, a gesture he had taught her earlier in the day. We wave a farewell, wishing Chhaidy’s fairytale ends in the way we like stories to conclude: happily ever after.

Victor of Aveyron

Of all the stories of feral children returning to civilisation, the most well researched and authenticated one is of a boy who was found near the forests of Aveyron in France in the 18th century.

The boy was first sighted in 1797 on the edge of the forest. Some hunters tried catching him, but he escaped. He was about nine at the time. Some time later, he was captured and put in the care of a local woman, but he escaped again. Then, on January 8, 1800, he emerged from the forest himself.

It was the age of scientific discoveries and theories, and several people experimented on him. When biology professor Pierre Joseph Bonnaterre made him take off his clothes in the snow, the boy happily romped around, unaffected by the cold. This made the professor conclude that human reaction to temperature was impacted by conditioning and experience.

It was clear he could hear, but he uttered no word. He was taken to the National Institute of the Deaf in Paris, where Jean Marc Gaspard Itard, a young medical student, gave him the name Victor and tried to teach him speech. He initially showed some progress but later slowed down. Itard abandoned the effort. Victor learnt only two words in his lifetime—lait (milk) and Oh Dieu (Oh God).

Victor died in Paris in 1828 at age 40, never completely adjusting to human society. He tried to escape at least eight times.

“Victor is a classic case study still discussed in medical school, specially in psychiatry. His example led doctors and researchers to conclude the importance of exposure to speech and language during the critical period from the age of around four. Later studies, however, concluded that the human brain is plastic enough, and there may be delayed speech development even in adulthood; it depends as much upon the individual,” says Satish Girimaji, head of child and adolescent psychiatry, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bengaluru.

Back from the wild: On returning home, Rochom initially preferred the chicken coop to the house.

Back from the wild: On returning home, Rochom initially preferred the chicken coop to the house.

Later researchers have also suggested that he might have had some form of autism, which prevented speech development.

Cambodia's Jungle Woman

In a story that has striking similarities to Chhaidy's, a woman materialised from the forests in Ratanakiri province, Cambodia, on January 13, 2007. A villager noticed food missing from his lunchbox and looked around for the thief, only to find a filthy, naked and hungry woman. As news of her discovery spread locally, Sal Lou, a man from a nearby village, claimed she was his daughter, Rochom P'ngieng, who was lost at the age of eight, some 18 years earlier. A scar on her arm and resemblance to his wife were the identification they needed.

A DNA test was suggested, but the family later withdrew consent. Rochom's integration into society hasn't been an easy one, though she has received more medical and psychological care. She has run away from home several times and was once discovered at the bottom of a sewage pit, where she had spent eleven days. For a long time, she preferred living in the chicken coop to living in the family home.

Rochom's tale has been questioned by many. Some do not believe her to be a lost child, but a person who was kept in shackles by someone and managed to escape. The scars on her wrists support this theory. Rochom, too, hasn't had much progress on the language front, uttering barely a handful of words.

Chhaidy, Victor and Rochom have several similarities in their tales. They appeared of their own volition before human settlements, which experts feel is the natural human instinct to bond with fellow humans. Yet, they tried escaping into the wild several times, which is also a natural tendency, as the wild had been home to them for years.

They all displayed bipedal locomotion, unlike in the fables where wolf-raised boys crawl on all fours. Doctors say that humans have evolved to walk on legs and, unless they have a problem with their limbs, they will do this instinctively.

Also, while they were discovered in a dirty and naked state, none of them exhibited severe nutritive deficiencies. “Nature provides enough for good nutrition,” says Girimaji.

Mother, nature: Ramu with Mother Teresa.

Mother, nature: Ramu with Mother Teresa.

None of them showed any progress with language, though their hearing faculties were well developed and they did understand simple sentences and instructions.

Lucknow's Ramu

The number of feral children stories reported in India is perhaps more than from any other part of the world.

According to newspaper reports of the time, Ramu was found in the company of wolves in a jungle in Sultanpur district of Uttar Pradesh in 1976. He was ten at the time, crawled on fours and preferred raw meat. Ramu was taken to Prem Nivas in Lucknow, run by Mother Teresa's charity, and lived there till he died of severe abdominal cramps in 1985.

Ramu was an international sensation, and scientists from across the world studied him. They concluded that his survival in the jungle was possible because he had been adopted by the wolf pack.

Ramu didn't take too well to civilisation and reportedly ran away to raid chicken coops at night. He led a quiet existence and never picked up human speech.

Original Mowgli

Dina Sanichar is not a name many would know. However, the character he is supposed to have inspired is a worldwide favourite—Rudyard Kipling's Mowgli, the hero of The Jungle Book.

Dina was around six when a group of hunters discovered him in a wolf's den in Bulandshahr region of present-day Uttar Pradesh in 1867. They were astonished to see that the boy followed a she-wo lf into her den on all fours. They smoked out the wolf, shot her companion and recovered the boy.

Sanichar initially showed animal-like traits, but was eventually persuaded to eat cooked food. He later picked up tobacco addiction. He never learned to speak and died in 1895.