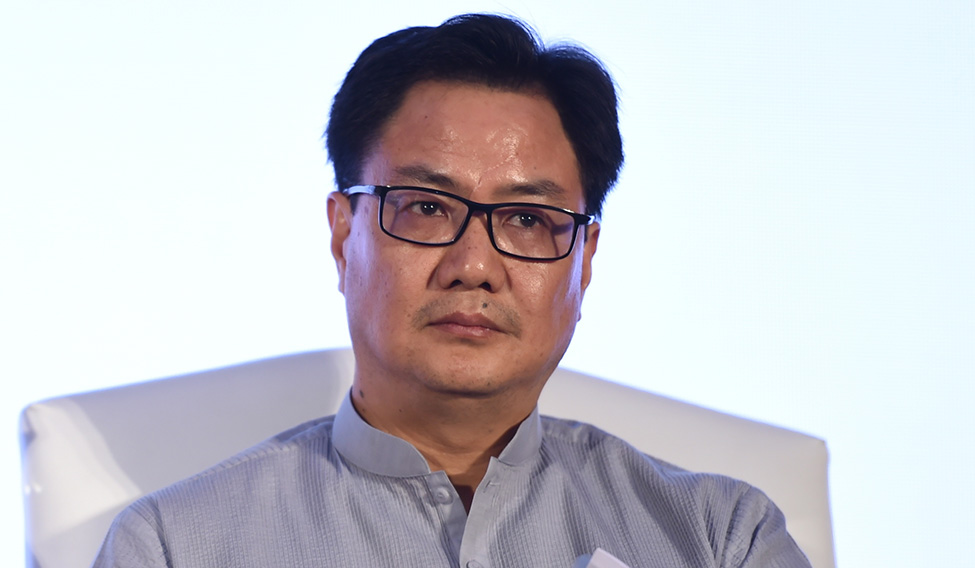

When Kiren Rijiju went vocal about the need to deport the Rohingya refugees, little did he realise that there might be trouble, literally in his backyard, just at that moment. First came the advisory of the Union home ministry's foreigners division, handled by the minister of state, asking state governments to identify Rohingyas and deport them. The home ministry termed them a national security threat.

The minister was echoing the sentiment of his government as well as the BJP, which is in power in Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, Manipur, Nagaland and Sikkim. These states claim to have suffered a demographic change with the influx of Bangladeshi migrants and do not want the Rohingyas settling down there.

When human rights groups decried the move to “deport” the Rohingyas, Rijiju talked tough: “Branding India as villain on the Rohingya issue is a calibrated design to tarnish India's image. It undermines national security.”

In the next few days, External Affairs Minister Sushma Swaraj was seen trying to do a balancing act. She called up Bangladesh Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, offering support to Dhaka's humanitarian challenges. But the home ministry in its affidavit filed before the Supreme Court on September 18 made it clear that the Rohingyas had links to terror groups like Islamic State and that they were a strain on national resources.

Little did the ministry realise that while it was racing to pack off the Rohingyas, it would soon be pushed to consider citizenship to another set of refugees. The Supreme Court asked the Centre to grant citizenship to the Chakma-Hajong refugees, who have been staying mostly in Arunachal Pradesh since 1964. According to the 2011 census, there are 47,471 Chakmas in Arunachal Pradesh. Rijiju, who is from Arunachal Pradesh, found himself caught in a tricky situation because the file landed on his desk.

In 2015, when the Supreme Court had first ordered citizenship to the Chakma-Hajongs, who fled from Chittagong in erstwhile East Pakistan in 1964-65, several groups in Arunachal Pradesh vociferously opposed it saying it would change the state's demography. On September 18, Chief Minister Pema Khandu shot off a letter to Union Home Minister Rajnath Singh seeking “protection of tribal rights and securing the sanctity of the inner line permit in Arun-achal Pradesh”. Rijiju said a “middle ground” would be worked out, but did not rule out full citizenship.

The home ministry is confident that its policy of dealing with illegal immigrants “on a case-to-case basis” has stood the test of time. Officials said while the Chakma refugees might be given citizenship, they would not be granted the right to purchase land. They may be allowed to work and travel after obtaining inner line permits. Sources indicated that the move to allow them to stay on as citizens could be in line with the government's stance of granting citizenship to those who have taken shelter in India after facing religious persecution. The Chakmas are Buddhists and the Hajongs are Hindus.

“The Supreme Court has ordered to grant them citizenship status and the MHA will respond in the court. But as per the constitutional provisions and various existing regulations, we cannot treat them at par with the indigenous people of Arunachal Pradesh,” said Rijiju. He said the Chakma-Hajong issue was different from the Rohingya crisis. “These cannot be compared.” More deft balancing will be needed from Rijiju in the coming weeks as the government comes under pressure on the Rohingya issue.