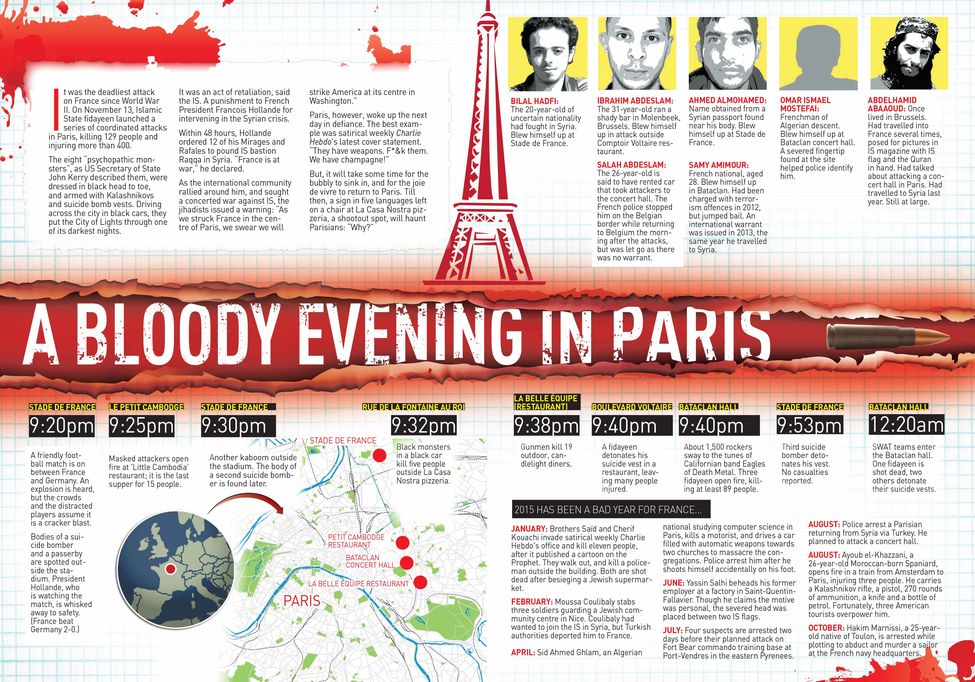

The first bomb went off 17 minutes into the friendly football match between France and Germany. President Francois Hollande, watching the match from the VVIP box at the iconic National Stadium in Paris, heard it. His aides worried.

Robin Panfil, sports reporter of Slate.fr., dismissed it as a cherry bomb, "common in the vicinity of stadiums". More perceptive, Financial Times columnist Simon Kuper tweeted, "We have now heard what sound like 2 bomb explosions right by the Stade de France. Play continues merrily. Some unease here."

Many outside the stadium gates, where the guards had stopped two men, heard them shouting, "Hollande has brought it on himself. He shouldn’t have sent bombers to Syria." No one inside the stadium, most of them loudly cheering France, heard them.

Meanwhile, the president got up and quickly left. But that is always so. Presidents rarely stay till the end of any match.

When they knew they couldn't get at the president, Bilal Hadfi and Ahmed Almohamed, the men who were stopped at the gate, pulled the fuse to the bomb vests they were wearing, making a second and a third bang. They ended their lives, believing that the gates of paradise would be opened for them if they went there after killing people on earth.

Today, the greatest challenge for Hollande and the majority of the French people, who pride themselves to be Europe's most liberal society, is to convince themselves that Islam does not say so. They also don't know, at least officially, how many amidst them harbour such beliefs. They don't even know how many among them are Muslims. The secular-liberal laws of France prohibit the government from even asking a citizen about his religious beliefs, even for the purpose of census.

Unofficial estimates put the Muslim numbers at five million or 7.5 per cent of the nation's population, the largest in any west European country. The challenge before the French people is to convince themselves that the majority of them harbour no such beliefs.

A few minutes and four miles away from the stadium, another such uncounted man, Ibrahim Abdeslam, who had been running a shady bar in the Brussels neighbourhood of Molenbeek and had been brainwashed by false preachers, blew himself up in the Comptoir Voltaire restaurant, after gunning down 15 diners and revellers.

Minutes later, yet another two gunmen, still not identified, attacked Casa Nostra pizzeria on Rue de la Fontaine au Roi, killing five diners. Then they got back into their rented car and, as an eyewitness said, "drove away very slowly, very calmly.” They drove to La Belle Equipe bar in Rue de Charonne, and sprayed bullets on 19 people.

At the Bataclan concert hall less than a mile away, 1,500 music lovers— "idolators of perversity" as the terrorist group Islamic State would call them later while claiming responsibility for the attacks—were watching the American rock group Eagles of Death Metal perform to a full house. At around 9.50pm, black-clad gunmen wielding AK-47s and wearing suicide vests stormed into the hall and fired calmly and methodically. At the end of a two-and-a-half-hour siege, in which they killed 89 people, Omar Ismael Mostefai and Samy Amimour blew themselves up. A severed fingertip later helped the police identify Mostefai. A third, whose name is not known, was shot dead by the police.

By midnight, the bloodbath had claimed more than 120 lives; more would die in hospitals. In liberal France, the dead are counted, not the living.

City under siege: Liberals worry that the IS attack on Paris will trigger a rightward march of French society and politics | Sanjoy Ghosh

City under siege: Liberals worry that the IS attack on Paris will trigger a rightward march of French society and politics | Sanjoy Ghosh

France knew this was coming. Since the attack on the office of the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo in January, there had been several successful, attempted and thwarted attacks that had clear jihadi signatures (see graphics). Two weeks ago, Bernard Bajolet, chief of its intelligence service, had gone to Washington where he made a public statement about the two kinds of threat France was facing, one from the young radicalised French residents, and the other "from outside, either through terrorist actions which are planned [and] ordered from outside or only through fighters coming back to our countries.” The gang of seven that Abdelhamid Abaaoud, the mastermind of the attacks, had formed consisted of both kinds. He even admitted that at least 500 French citizens are fighting in Syria and Iraq, and that the total number who have gone there and been killed or returned may be triple of that.

Now the whole world is standing by France, but France knows that it is also being blamed for its liberal ways, its liberal laws, and its liberal police. A law that does not allow the police to arrest people even if the police knew they were up to crime. A law that Hollande is now under pressure to change.

Every one of the attackers was known to France's lawmen. Each one had popped up in their S-Files, an index of individuals who are suspected to be dealing in shady things. Virtually all of them were in the files, for having preached radicalism, for having travelled to Syria, for having run shady bars in neighbouring Belgium or for having aided other terrorists somewhere.

Take Mostefai. He had been arrested several times for petty crimes, and convicted eight times, and the sleuths had known that he was a "high-priority target" for radicalisation. He had also been in the S-Files, but as prosecutor Francois Molins said, nothing could be done because he had "never been implicated in an investigation or a terrorist association".

Take the Abdeslam brothers. The eldest, Ibrahim, blew himself up outside the Comptoir Voltaire restaurant. He, too, had been in the S-Files, and he had even used his real name and driving licence to rent a Belgian car which he drove to Paris.

The police have now put out a warrant for his brother Salah, the one that got away, thanks to their 'liberal ineptitude'. They had stopped him on his way to the Belgian border while he was driving back after the night of the massacre. They questioned him, but didn’t detain him because there was still no look-out warrant for him!

Or take Abdelhamid Abaaoud, the mastermind who got away. The police had everything about him in the S-Files, that he had gone to Syria in 2013, that he had been harbouring ideas of hitting a concert hall (he had told so to another IS recruit whom the police had apprehended a few months ago). He had even bragged to the IS magazine Dabiq, how he had easily travelled through Europe. “My name and picture were all over the news," he had mocked at the French police. "Yet, I was able to stay in their homeland, plan operations against them, and leave safely when doing so became necessary.”

It is not the liberal law alone that is being blamed. “The services are overwhelmed,” said Jean-Charles Brisard, head of the Paris-based Centre for the Analysis of Terrorism. “When you consider it takes 25 officers to provide round-the-clock surveillance on one individual, you can see the difficulty.” No wonder, post-blasts, Hollande has asked for recruiting 10,000 more policemen. Terrorism becomes a job generator.

Now, the leaders of the National Front, France's far right party, have started demanding a crackdown on all those who figure in the S-Files. There had been similar demands in the past, especially when it was found that two of the Charlie Hebdo killers had figured in the files. But on all those occasions the socialist regime dismissed them with the support of France's outspoken liberal intellectuals. But this time, the government, too, is willing to listen. "You can't dismiss any tool," said Prime Minister Manuel Valls. "We will examine all possibilities... We are not setting aside any solutions."

Rescue workers leading a victim out of Bataclan. IS terrorists gunned down 89 people in the theatre | AP

Rescue workers leading a victim out of Bataclan. IS terrorists gunned down 89 people in the theatre | AP

The fear among the liberals is that the extreme reaction from the public, especially the far right politicians, would force France to shed its liberalism which had come to equate the republic's motto of 'fraternity' with the Islamic concept of 'brotherhood'. All that seems to be changing. Significantly, after the Friday the 13th attacks, there has been little of symbolic fraternising with the Muslims, the kind of which one witnessed after the Charlie Hebdo attack. "After the Charlie Hebdo incident, we had several people coming out making grand public statements of solidarity with the Muslims," said tourist guide Hassan Abu, a Moroccan. "Many were crying 'fraternity, fraternity' at that time. We don't see anything of that kind now." On the contrary, hate speech has started appearing on social media. "We are worried," said Hassen Farsadou, head of a suburban Muslim community group. "We are trying to figure out how to handle this."

The realisation has made Hollande declare that France is at war, and declare a state of emergency which would allow the police to question people on suspicion, ban radical assemblages, and also expel preachers of hate from French soil. "We need to expel all these radicalised imams," said Valls. Yes, French laws have been tolerant of even radical preaching. Now Hollande has asked his parliament, which met in Versailles on the Monday after the blasts, to make laws that would end some of the country's "frustratingly liberal laws", as an officer in the Paris prosecutor's office put it.

Rest in peace: A girl cries outside the French consulate in Sao Paulo, Brazil, paying homage to the victims of the 13/11 terror attacks in Paris | AFP

Rest in peace: A girl cries outside the French consulate in Sao Paulo, Brazil, paying homage to the victims of the 13/11 terror attacks in Paris | AFP

Ironic it would seem, early on November 18 morning, barely six hours before the cabinet was to meet to consider the new laws, the terrorists forced the government's hand. A police raid in search of Abaaoud in the northern Paris suburb of St Denis, led to a woman terrorist holed up in a house there blowing herself up and a man being shot dead by the police. The incident led to a prolonged siege of the locality, the kind of which France had never seen.

The incident, more than anything else, highlighted before the nation the need for tighter laws. For, under ordinary circumstances, the law permitted the French police to raid any building only between 6am and 6pm, and that, too, only after notifying the neighbourhood. Second, the constitution has mandated that even the special emergency laws (which, among other things, allowed raids) that Hollande had decreed on the November 13 would have to be withdrawn within 12 days. It was to amend these provisions, and to extend the emergency laws for three months, that Hollande had asked for constitutional amendments, and ironically, the terrorists gave him the handle.

The socialist regime's new leaning to the right has been welcomed with some rare praise by the National Front leader Marine Le Pen who has been demanding that France's borders be closed to refugees, and has been calling for stricter laws to monitor Islamic radicals. "France and the French are no longer safe," she said in a speech a day after the attacks, repeating her demand for blocking the refugees.

Meanwhile, the discovery that Almohamed had recently entered Europe through Greece has led to demands from European right-wingers to stop taking refugees from strife-torn Syria and elsewhere.

The worry of the liberals is that this would be the beginning of the end of France's liberalism. Said Farhad Khosrokhavar of the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales: “There is likely to be more of a shift to the extreme right, which will become stronger in the months to come.” Sophie Barreto, who works in Sorbonne, said, "That will be the end of liberal France, or even liberal Europe. And that is what the enemies of France want."