Shafi | PTI

Shafi | PTI

Jaali Road in Bhatkal town leads to one of the most picturesque beaches of Uttar Kannada district in Karnataka. The waves crash against rocks near the beachside ‘American Bungalow’, creating a symphony with the gushing wind. The evening sky and the Arabian Sea turn darker, as rain invades the coastline.

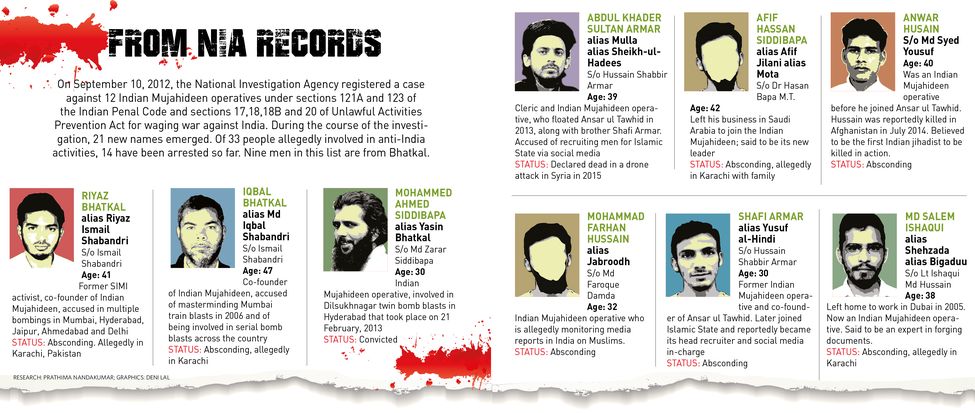

Bhatkal, too, has a dark side, the brothers Iqbal and Riyaz Shabandri, co-founders of the Indian Mujahideen, being its sons. The sleepy town grew darker on June 15, when the United States state department declared Shafi Armar a specially designated global terrorist. Shafi had vanished from Dubai ten years ago, about a year after he had been declared dead in a drone attack in Syria.

A native of Bhatkal, Shafi, 30, is the first Islamic State leader from India to be put on the American terror watch list. “He has cultivated a group of dozens of ISIS sympathisers involved in terrorist activities across India such as plotting attacks, procuring weapons and identifying locations for terrorist training camps,” the US state department said. “He is the leader and head recruiter in India for foreign terrorist organisation (FTO) and Specially Designated Global Terrorist (SDGP) group.”

At Hamza Nagar, a ghetto mostly occupied by Muslim families, Shafi’s ailing mother Hajira, 60, lives with her youngest son, Safwan, and his bride. Their house is no match for the sprawling bungalow of terror convict Yasin Bhatkal in Maqdoom Colony two kiometres away.

The house is locked from inside, as curious neighbours loiter around. Some neighbours plead with the reporters to get the family vacated from the locality. Safwan is not at home; he has gone to Visakhapatnam.

“Ammi se door raho [Stay away from mother], she is very sick. I am telling you people [media], I will answer all your queries once I return home,” Safwan screams over the phone. He later confides that the unwanted attention has ruined their lives. “My father is dead and my mother is sick. The last time they gave ammi the news of bade bhai’s death [Sultan died in a drone attack in Syria in 2015], she had to be hospitalised. Again, they came to our house with news of Shafi’s death. Now, they say he has been declared a global terrorist by the US. My question is, where is the proof?” asks Safwan. “I have seen nothing in writing, no documents for any of these claims.”

The rented house where Shafi’s mother and younger brother, Safwan, live.

The rented house where Shafi’s mother and younger brother, Safwan, live.

A police officer in Bhatkal confirms that the Na-tional Investigation Agency had issued a warrant against 15 people, including seven from Bhatkal—Shafi Armar, Sultan Armar, Riyaz Shabandri, Iqbal Shabandri, Hafif Geelani, Farhan Bhatkal and Maulana Shabbir Gangawade. “The local police stuck the warrant in all the public places and on the doors of the accused. But no one appeared before the court and they went absconding,” says the officer.

Safwan worries that the agencies are trying to frame him.

Safwan worries that the agencies are trying to frame him.

According to the police, both Sultan and Shafi left Bhatkal around the same time in 2006, and came under the police scanner in 2008. It was after Yasin Bhatkal’s arrest in 2013 that the NIA and Mumbai’s Anti-Terrorism Squad confirmed the Armar brothers’ involvement in terror activities. Following his arrest in Kolkata, Gangawade revealed that the Armar brothers had attended a meeting at American Bungalow (called thus because the owners, who rented it out, live in the US). The Armar brothers left for Pakistan after the crackdown on Indian Mujahideen cadres. They had a fallout with the Bhatkal brothers there. Shafi then created his own group called Ansar ul Tawhid, which pledged its allegiance to the Islamic State.

While the local police keep an eye on the families of the suspects, the investigation and surveillance are mostly carried out by the central intelligence agencies and ATS independently. Some officers in the Intelligence Bureau feel that competitive policing is to blame for the accused escaping from India. They say the agencies work in silos and do not share information.

Safwan worries that the agencies are trying to frame him. “They keep hounding us. Officers without any identity card often walk into our house and ask us about Shafi; whether he sent us money to buy a new house, when we have always lived in a rented house,” says Safwan. “When I got married last October, there were some people secretly filming my wedding. We trust the Indian judiciary. Let there be a trial, and if Shafi is guilty, let him be punished.”

After some prodding, Safwan gives a glimpse into his family. “My father, who used to work in a hotel in Mumbai, came back to Bhatkal some 15 years ago. But, following an accident, he was bedridden and he passed away three years ago,” says Safwan, who works in a printing press. “My two sisters are married into families in Bhatkal. My eldest brother, Khalid, works in Dubai and his family never visits Bhatkal. Sultan studied in Lucknow [to become a maulvi] and left for Muscat. Shafi left for Dubai in 2006 to work as a real estate agent. But his firm shut down. He has not been in touch with us for eight years now. Initially, Shafi was in contact with us for two years, but soon he vanished. We started hearing stories of his involvement in terrorist activities. But till today, no official document against him is there, except for the NIA warrant naming Sultan and Shafi, which was pasted on our door.”

The Ramadan season is special in Bhatkal, which has 70 mosques. The Navayat Muslims in the region are affluent, thanks to their enterprising spirit and links with the Arab world intact through trade and marriage. The Hindu localities have been pushed to the periphery, yet the right-wing politics has elbowed its way into the region in the past three decades.

Some educated Muslims who could not make it big are making a fast buck through terror activities. “In 2004, Bhatkal became the breeding ground for terror operatives,” says a senior IB officer. “Like Azamgarh in Uttar Pradesh, Bhatkal, too, became notorious as Iqbal and Riyaz Shabandri started recruiting cadres for IM. It is no coincidence that a majority of the Bhatkal youths linked to terror belong to the Navayat community.”

Shafi’s portrayal as Islamic State’s head recruiter and social media in-charge is an exaggeration, argue intelligence officers. “Shafi might have been an informer for Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence, but he is a school dropout and not a genius. His role in IS is hyped and so is his role in recruiting people from India through the internet. He is not bright like the Bhatkal brothers,” says an IB officer, who was monitoring Shafi before he vanished.

Just when the agencies were rueing that they could not apprehend the absconders, an opportunity showed up. The news of Sultan’s death was conveyed to the Armar family by the IB officers, who kept a close watch on them. As expected, a special prayer was offered for Sultan at a local mosque.

It was strange, recounts an IB officer, as the Armar family refused to believe Sultan was dead and demanded evidence. But they quietly offered prayers, which indicated they got confirmation from some other source. “The agencies have not been able to break through the communication channels of these families as a relative or a family member is the key link,” says the officer.

The Majlis-e-Islah-o-Tanzeem, the highest religious body of Muslims in Bhatkal, has distanced itself from the terror suspects and their families. “We are not aware who this boy [Shafi] is. Neither do we support him nor do we have any links with him. We are against such activities and whoever is involved in it should be condemned. If these guys were innocent, they should have approached the Tanzeem. But they have not done it,” says Muzammil Qasia, president of Tanzeem. His only grouse is that the word Bhatkal is being used as a tag for the terror suspects.

According to Dr Mohammad Haneef Shabab, former general secretary of Tanzeem, Bhatkal has become a target of conspirators who are against the Islamic identity. “Thirteen Muslims were killed in the communal riots in Bhatkal in 1993, but there was no retaliation. How can you link Bhatkalis with terror?” asks Shabab, a unani doctor. “Like Osama bin Laden’s death, this, too, is a claim made by the US. Do the IB or the media have any proof against them?”

The social isolation of the families is a major deterrent for any terror network to flourish, says an IB officer, who believes it is endgame for terror operatives in India. “A majority of Indian Muslims have no affiliation with the Alhadi sect, which believes in radical Islam, and the Indian Mujahideen is defunct, with its core members either arrested or under the scanner,” says the officer. “A closer look at the IS recruits reveals that the Indian recruits were never in combative roles in the armed conflicts as only the well-built Arabs and the Muslims from the European countries were preferred. The terror network is controlled by the European Muslims, and the Indian recruits are like errand boys doing menial jobs or they are assigned media operations as they are good with computers. Islamic State wants to exploit the intellectual capability of the Indian youth to spread terrorism in the region. Indian Muslims have realised that terror propaganda is no longer based on religion or ideology, but is meant to satiate the greed of a handful of people.”