In 1978, Robert Geesink reached India a broken man. Hampi, however, gave the Dutchman hope. And, though the village in Karnataka was in ruins, much like his mind, the peace and solace beckoned him. It gave him a surreal landscape and a blank canvas. His artistic thirst was quenched.

For 37 years since, Robert's love of Hampi has survived and thrived. He produced hundreds of paintings based on local culture and four children with two Lambani wives. “Hampi was very different then; you could live wherever you wanted, without any authorities bothering you,” he says.

Over the years, Hampi's mystic charm has attracted many foreigners. For instance, Cesare, a wealthy Italian, left his country in the 1970s to be a mendicant and travelled with yogis. He soon found a cave on an island in the Tungabhadra river, set up a Shiva temple there and has stayed put since.

Rangit Sanhaie: Sanhaie with his stepdaughters, Lakshmi and Asha. The Englishman came to Hampi in 1999 with his partner, a Lambani woman from Kaddi Rampura. He married her in the Virupaksha temple. Since her death, Sanhaie has been living with his three stepchildren.

Rangit Sanhaie: Sanhaie with his stepdaughters, Lakshmi and Asha. The Englishman came to Hampi in 1999 with his partner, a Lambani woman from Kaddi Rampura. He married her in the Virupaksha temple. Since her death, Sanhaie has been living with his three stepchildren.

That was a time when the Hippie trail was popular. Many westerners looked east for a simpler life and, as Hampi found its place on the Hippie map, it became common for visiting foreigners to change their names and settle down.

Francoise, for instance, came from France shortly after Cesare and stayed with an Indian sadhu at the nearby Anegundi village. She changed her name to Sharada and had a daughter, whom she named Anjanadevi. Now 38, Anjanadevi, or Anjali to the villagers, is a gram panchayat member. “I am suggesting installation of water filters and toilets in the village for tourists,” she says. “I have plans to work with the Hampi World Heritage Area Management Authority to beautify the neglected monuments in Anegundi village.”

Even more at home is Meera, a Belgian sadhvi. Always clad in black, she stays with a few dogs in a cave close to Cesare's temple. She fetches water from the river and firewood for cooking every day, and runs an NGO for village women who make artefacts from banana fibre.

For more pics: Hampi go lucky

However, when the Hippie era ended, interest in mysticism and spirituality faded. But Robert, Cesare, Sharada and Meera had tasted life in Hampi. They had no intention of going back. They gave up possibly posh lives in the west and put their papers in order.

Most of these expats are senior citizens and get social security money from their countries. This allowance usually finances their Hampi stay. Now, they only go back to their homelands to renew their visas and for other official purposes.

Graham Purchase: In 1996, the Australian anarchist author was lured by the reclusive air of Kaddi Rampura, a village near Hampi. An avid cyclist, Graham leads a simple life―no smartphone, no internet and no stress. He smokes local bidis and rides an Indian bicycle.

Graham Purchase: In 1996, the Australian anarchist author was lured by the reclusive air of Kaddi Rampura, a village near Hampi. An avid cyclist, Graham leads a simple life―no smartphone, no internet and no stress. He smokes local bidis and rides an Indian bicycle.

Interestingly, the foreigners kept coming even after the Hippie era. In 1996, Graham Purchase, an Australian anarchist author, was lured by the reclusive air of Kaddi Rampura, a village near Hampi. An avid cyclist, Graham knows the roads like the back of his hand. He leads a simple life―no smartphone, no internet and no stress. He smokes local bidis and rides an Indian bicycle. His only complaint is that the brandy shop has been shut down at the instance of the temple priest.

Also enjoying the local life is Rangit Sanhaie, an Englishman who came to Hampi in 1999 with his partner, a Lambani woman from Kaddi Rampura. He married her in the Virupaksha temple. Since her death, he has been living with his three stepchildren. The farmhouse they live in, he says, is the perfect place to strum his guitar and relax. Rangit also plays every Saturday at the party organised by the expats. Robert, asthmatic from years of chillum smoking, plays the vintage brass saxophone at these dos. They call their jam group Hampi Rocks.

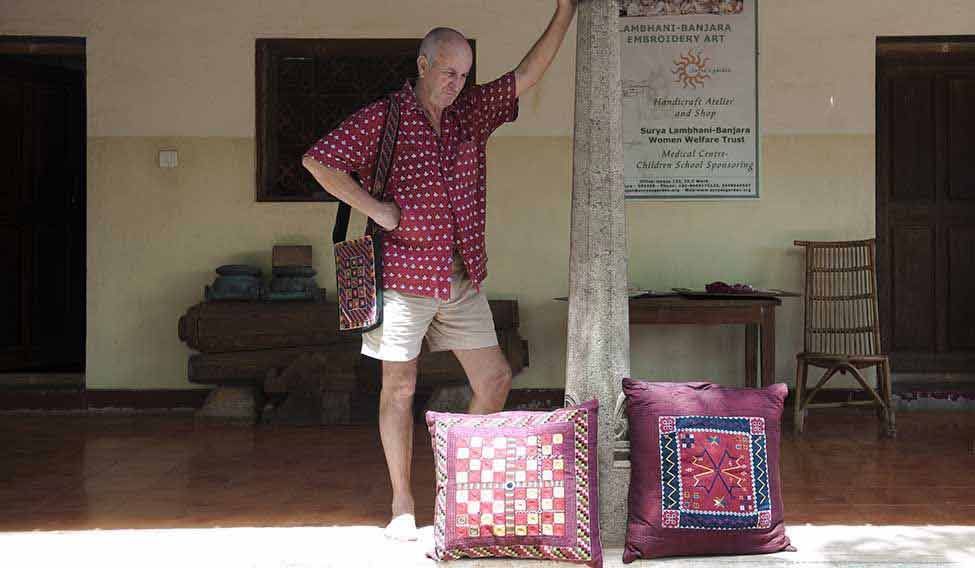

Another foreign resident is Parisian Jan Duclos, who lives on the outskirts of Kaddi Rampura in his self-designed botanical garden. His wife, Lakshmi Bai, runs an NGO to support the education of Lambani women and children, and a handicraft shop that features old embroidery designs of the Banjara tribe.

Dutchman Jan Wim Bugle, too, came to Hampi in the 1990s. A retired history professor, he is an amateur photographer and cartographer. He has climbed almost every peak in Hampi and his collection of photos includes a picture of the Anegundi bridge, just hours before it collapsed. When not working, Bugle sits on the roof of his farmhouse, poring over books on his e-reader.

An eclectic bunch, these foreigners. Leaving cosy lives in Europe to find peace and quiet in India. Truly, home is where the heart is.