On a corner plot in Bengaluru’s posh Dollars Colony stands the spacious bungalow that belongs to the Indian music world’s power couple. Inside, an exquisite, 4ft-tall statue of Lord Ganesh welcomes you to the home of legendary violinist Dr L. Subramaniam and playback singer Kavita Krishnamurthy.

Subramaniam and Kavita, his wife, have released an album for which they collaborated with the renowned London Symphony Orchestra (LSO). The album, named Dutta Symphony, was recorded at the famous Abbey Road Studios in London, known for its association with famous bands such as The Beatles and Pink Floyd.

The album’s main piece is ‘Dutta symphony’, which Subramaniam was asked to write for Ganapati Sachidananda Swamiji in Mysuru, on the occasion of him turning 75. The piece is a featured solo that has Kavita performing with LSO. ‘Astral symphony’, a 13-minute piece, was written several years ago for their daughter, vocalist Bindu. Its concept, of having western orchestra with non-western soloists, had not been tried at the time it was written. Bindu and her brother, violinist Ambi, have together performed the piece. The concluding piece, ‘Isabella concerto’, was recorded by Subramaniam and was commissioned by the Spanish Orchestra in January last year, to celebrate 60 years of diplomatic relations between India and Spain.

But it is not just the album that has Subramaniam and Kavita all revved up. They have finished work on ‘Bharat symphony’, commissioned by the City of Chicago. “They [the city government] asked me to write a piece celebrating 70 years of India’s independence,” says Subramaniam. “They are organising a concert in Millennium Park, Chicago, which will premiere on September 9.”

Stringed sentiments: Subramaniam with his violin collection | Bhanu Prakash Chandra

Stringed sentiments: Subramaniam with his violin collection | Bhanu Prakash Chandra

The symphony traces the history of India. “Vedic period, Mughal period, British period and post-British period—four sections, four movements of the composition,” he says. Along with LSO, he is “supposed to do this project in five continents, with Kavita as the main vocalist—from beginning to end. I am also playing the last movements.”

A doctor by training, Subramaniam holds a PhD in music, apart from five doctorates conferred on him by various universities. He is also a collector of violins. “I have three cupboards full of violins, one in Bindu’s room, one in Ambi’s and one in ours,” he says.

His collection includes a beautiful violin from Spain, with intricate designs on its back that resemble a mix of Arab and Christian worlds. Upon receiving it, he named it Isabelle on a whim. As it happens, the queen of the region where the violin was made, Valladolid, was also called Isabelle! His collection also boasts the world’s smallest violin, given to him by “a saintly person who used to teach meditation in New York, at the United Nations: Sri Chinmoy”.

His favourite, however, is the one he used to perform at the New York Philharmonic in 1985, after legendary conductor Zubin Mehta approached him to write a piece to celebrate India. “The vice president of a violin company came and said, ‘I want you to play our violin at the New York Philharmonic’,” says Subramaniam. “I used to play a different kind of violin back then—a four-string one—and he came and gave me three violins and told me to use any one of them. I said, ‘I’ll try’, because the violins were of a different kind. He brought over one four-string and two five-string violins. I liked one of them, and that is the violin I use even now.”

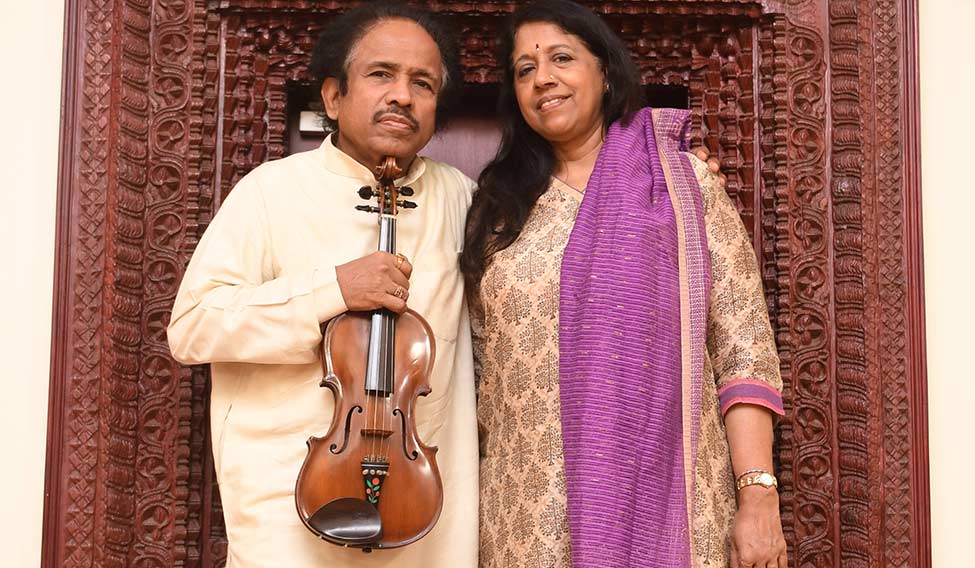

with Kavita and family at their home in Bengaluru | Bhanu Prakash Chandra

with Kavita and family at their home in Bengaluru | Bhanu Prakash Chandra

The piece he wrote was called ‘Fantasy on Vedic chants’, which he dedicated to his mother, who had passed away the previous year. His father, violinist V. Lakshminarayana Iyer, had flown in to New York to attend the concert, and so “sentimentally, it became very big”.

Subramaniam, whose first concert was in Sri Lanka when he was just six, attributes his success to his parents. He recalls how his father’s dream was to develop the violin as a solo instrument. “The whole tradition of violin was an ‘accompanying’ tradition—accompanying a vocal or a flute or veena. His dream was to see the violin played all over the globe as a solo instrument. He used to say that, whenever people went abroad, they performed at house concerts or had soirees, usually at a doctor’s house or in somebody’s basement, especially on weekends, which would be followed by potluck dinners…. More of a get-together than a professional concert. Being the visionary that he was, he realised that it was important to change the whole style of playing and to create a technique.”

Iyer went to Sri Lanka in the 1930s as visiting professor at Jaffna College and later moved to Colombo, where he headed Radio Ceylon’s orchestra. He was instrumental in changing the country’s music scene. “Whatever the violin’s position is today, in terms of Indian music, is completely because of him,” says Subramaniam.

After he completed his postgraduation in western music in the US, Subramaniam was asked to stay back, as his father wanted him to “try and change the scene there”. “My father’s vision became my vision,” he says. “Then I got married [to singer-composer Viji Subramaniam] and unexpectedly, my career started in a big way there, and I did some major work.”

Subramaniam and Viji had four children, including Bindu and Ambi. She succumbed to cancer in 1995. Four years later, Subramaniam married Kavita.

In Bengaluru, he and Kavita usually wake up by 8am, when their granddaughter, Mahati, goes to school. This, despite Subramaniam going to bed only between 2.30 and 4am. “Concert days are geared towards air travel and sound checks,” says Kavita.

On other days, she says, things are quite relaxed, except for her practice sessions and homework. “For instance, for ‘Bharat symphony’, I have to do a lot of homework,” she says. “I don’t read western music, you see…. I don’t like to have a sheet of paper in front of me on stage, which means I have to know my cues. Sometimes he [the conductor] will give me a cadenza, which is a free improvisation. If it is a raga that I am not very familiar with, then I have to familiarise myself with it, which cannot happen in a day. That’s why the homework.”

Does Bollywood songs demand that kind of preparation? “A two-hour Bollywood concert can be quite a strain,” says Kavita. “Most of my songs are very high-pitched. From [A.R.] Rahman to Laxmikant-Pyarelal, composers have given me high songs. So I have to be prepared.”

Subramaniam’s morning routine involves meeting visitors, including violin students, and going over technical details of concerts. “Mahati comes around in the afternoon. When I am there, I teach her violin, which she has started learning seriously. Sometimes, she forces me to sit and sing, and at night, after she goes to sleep, I start writing.”

After his father died in 1990, Subramaniam started the Lakshminarayana Global Music Festival, which provides a platform for talents and different styles of music from around the world. He also started a music school, the Subramaniam Academy of Performing Arts, which Bindu and Ambi now run. “The idea was to give every child an opportunity to get exposed to music. Learning music expands your mind,” he says.

While Kavita’s students in the US are awaiting her return to that country, Subramaniam wants to continue writing so that people will be aware of the treasures of Indian music. His symphonies are being published by Schott Music, which originally published Beethoven and Bach in Germany.

Subramaniam says he enjoys listening to Tchaikovsky’s symphonies, which “take you somewhere else”. It is this power of music to transform the temporal world that continues to inspire the couple. “Once you start playing, the sound takes over and an inner voice guides you,” says Subramaniam. “You forget where you are and who you are playing for. From there onwards, you just obey and follow. Even after you have finished playing, you feel calm for hours. It is a state of mind that is so blissful.”