The constant chatter of a kid from inside is a distraction for some of us engrossed in our cellphones in the living/waiting area of actor Nawazuddin Siddiqui’s office at Zohra Aghadi Nagar at Versova in Mumbai. The kid wants to take her papa home, but the papa is busy. Siddiqui had returned from a trip to Melbourne early that day. He had attended the Indian Film Festival of Melbourne and had also been on an extended vacation with his family, “a much-needed holiday” after five years of hard work.

Shora, the actor’s five-year-old daughter, hasn’t got enough of her father. She wants to spend some more time with him. But Siddiqui has to promote his new film, Freaky Ali, which will hit theatres in September.

Just before we settle down for a chat, Shora insists again that he come home with her. He negotiates with her for a few more minutes. “Aap chalo, main aata hun [You go ahead, I will come],” he says. “Aap kaise aaoge? Aap toh itne intelligent bhi nahi ho. Aapko toh rasta bhi nahi dekha hua [How will you come? You are not so intelligent and you don’t know the way home],” replies Shora.

Amused, we tell her how her dad cannot be not-so-intelligent—he won an award just a day before, for Best Actor for Raman Raghav 2.0. “So what?” she asks. “I also won an award in school; and he can’t speak in English, too.”

Siddiqui prefers to talk in Hindi; his English is halting. Later, we ask him whether that has ever been a drawback, and he turns defensive. “Who says I can’t speak English?” he asks.

But he is back at ease in a flash. “When I am abroad, I speak in English and people understand it well,” he says. “Par hamare yahan, jab English bolte hain toh log kehte hain, ‘Arre yaar, kyun koshih kar raha hai?’ [Here, when I speak in English, people ask, ‘My friend, why are you trying?’]. They make you conscious because it is a status symbol for them.”

But things have changed and not being of a certain type isn’t a setback anymore in bagging roles. Maybe that is the reason he has got Freaky Ali, an out-and-out commercial film presented by Salman Khan and directed by Sohail Khan. It is a departure from many of the alternative and middle-of-the-road films that he has done. Unlike in his previous commercial outings like Kick and Bajrangi Bhaijaan, he is not playing second fiddle here, nor is he part of an ensemble, like in Gangs of Wasseypur. His last solo, Manjhi: The Mountain Man, was also termed an offbeat venture, probably because he wasn’t dancing around the trees.

Likeable, on and off the screen: Siddiqui with his family.

Likeable, on and off the screen: Siddiqui with his family.

It is Siddiqui’s hard work that has paid off. “Till 2012, I had done very small films, some 12 to 14 of them,” he says. His actual journey, he says, began in 2010, with roles in films like Talaash, Kahaani and Gangs of Wasseypur. “There has been no magic. It’s hard work. I did small scenes 10 years ago with as much honesty as I do the bigger roles now,” he says.

Every film teaches him something new and helps him grow. Din mein karenge jagrata, a song in Freaky Ali, sees him dancing like never before. The last time he was seen frolicking a bit was in 2009, in Dev.D’s popular Emosanal Atyachar. Siddiqui isn’t hesitant to accept that in so many years of acting, this is the first time he has done a choreographed number. “It was scary in the beginning. I hadn’t done it before and it made me conscious. But Rajeev Surti [the choreographer] understood that there’s a rhythm in every individual. He let me understand mine and let me do whatever, and however, I wanted at the initial stage. Once I opened up, he choreographed it,” says Siddiqui.

While very little is known about Sabbir Khan’s Munna Michael, which stars Tiger Shroff and him, it is said that he would be dancing in that film, too. Siddiqui will also essay the role of author Saadat Hasan Manto in Manto, directed by Nandita Das. “Main actually saari cheezein wahi karna chah raha hun jo kiya nahi hai abhi tak [I want to do everything that hasn’t been done yet],” he says.

Siddiqui swears by versatility. He plays a suave golfer in Freaky Ali and may learn classical music to play a music teacher in Sarthak Dasgupta’s The Music Teacher. For the past five years, he has been getting a variety of roles to satisfy his actor’s appetite. His dream role is to play Salim in a revival of Mughal-e-Azam.

Siddiqui says he has been inclined to do romantic roles since the beginning of his career. “I have always wanted to do love stories. Now, they are coming to me. I have also told directors to offer me such roles,” he says. “In the next year and a half, you will see me in a different type of romantic films.”

Siddiqui’s choice of films has been winning him accolades—from Manoj Bajpayee wanting to do the roles he has got (as in this case of Manto) to Naseeruddin Shah expressing his envy about the way his career is shaping up. “It’s a big leap for me,” says Siddiqui. “Directors have started believing that I can do a variety of roles and there is nothing better than it.”

Anurag Kashyap, who has given Siddiqui several critically acclaimed roles, has described him as a director’s actor. And Siddiqui takes pride in it. “It’s important to understand how the director is looking at the character,” he says.

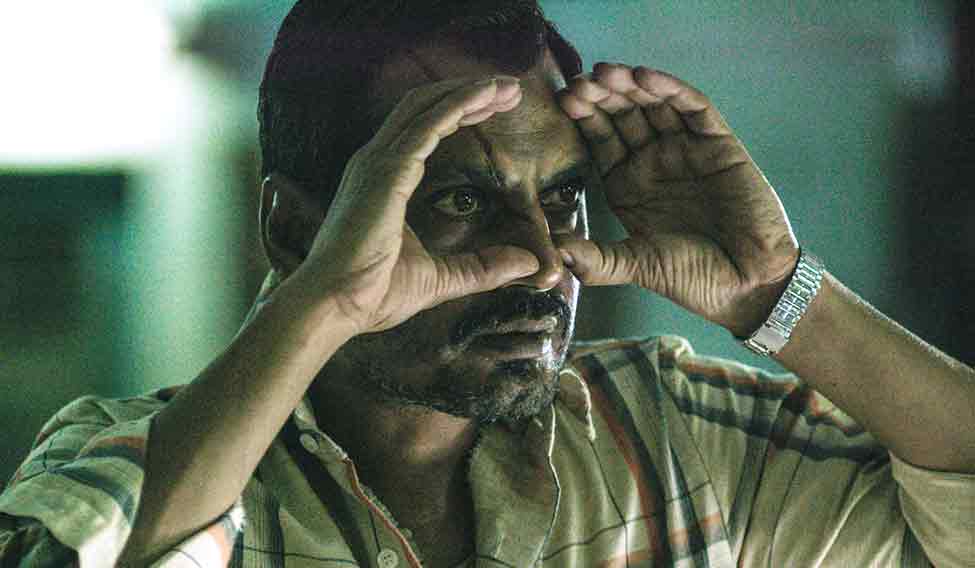

Siddiqui in Raman Raghav 2.0

Siddiqui in Raman Raghav 2.0

He is in touch with Sabbir and Das to understand the characters he is playing in their films. He reveres Manto and his stories, and is trying to understand how Das looks at Manto. “There is no video of him [for reference], so I have to imagine how he would be. I am not watching any films made on him. His stories will help me understand that,” he says, pointing towards a shelf stacked with books by Manto. Thanda Gosht, Khoon Do, Kali Shalwar are some of his favourites. He has been reading Manto since his days at the National School of Drama in Delhi.

It is around this time that I ask him about his English, and he recalls how an English-speaking student left a big impact on the teachers at NSD, even though the student was repeating the same thing that was said earlier by Hindi-speaking students. Such is world, he says, “too worried about image and status”.

Going to Hollywood, according to him, is also an image-building exercise. “Hollywood doesn’t give you work because of your talent, but because you have agents who are well-placed in the system, to look for work for you and place you in their projects,” he says. “If something [Hollywood film] comes to me easily, I don’t mind doing it. But I am proud to be associated with films in India. We are growing tremendously on the global map and I don’t need a Hollywood project for value addition.”