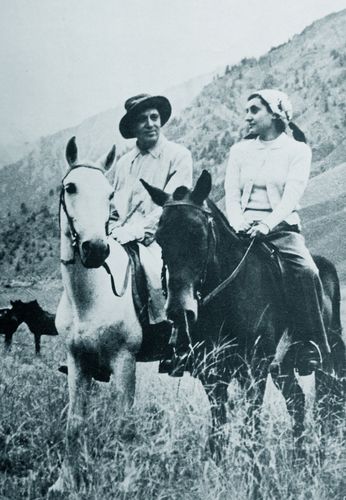

In her father’s footsteps: Indira Gandhi is said to have inherited her love for nature from Pandit Nehru | Courtesy: Teen Murtilibrary

In her father’s footsteps: Indira Gandhi is said to have inherited her love for nature from Pandit Nehru | Courtesy: Teen Murtilibrary

On March 20, 1977, when Indira Gandhi lost the general elections, she wrote two letters. The first was to the chief minister of Assam, regarding protection of forests. The other was to the ministry of petroleum, regarding protection of the Sunderbans.

“She was amazing. At the most crisis-riddled moments in her life—and there were plenty of them—Indira Gandhi was worrying about the environment,” says former environment minister Jairam Ramesh, a Rajya Sabha member. Ramesh is out with an interesting biography of a woman who has been much written about. It looks at Indira, on her birth centenary, through the prism of environment.

Indira Gandhi: A Life in Nature is a compilation of her correspondence, which Ramesh collected mainly from the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library, National Archives, the Smithsonian Institution and Sonia Gandhi’s personal collection. It traces the journey of Indira, from a child communicating with her father, Jawaharlal Nehru, who was often in jail during her formative years. She grew up reading The Life of the Bee, The Faber Book of Insects and The Life of a Butterfly. There is a young Indira, incarcerated at Naini jail in 1943, fascinated by a birdsong. She writes to her father, who was in Ahmednagar jail: “was singing on a warbling, whistling note. It took me quite a while to locate the sound as coming out of the peepul (this is a feat, the sound being thrown back and forth by the high walls). Just as I got under the trees, the bird gave an extra loud whistle and away he flew. All I saw a bit of beige, a bright tail in two dazzling shades of blue, a long dull red curved beak. Can you tell us what it is?”

The father replies, two months later: “give me a vague description of a new bird you saw and want me to name it from here! This faith in my extensive knowledge is very touching but it has not justification.”

As a young lady, Indira writes about her travels through Switzerland with Feroze Gandhi, and here again, the description of nature is vivid, personal, and heartfelt. Says Ramesh: “I joined the government in 1983, and in 1984, she was assassinated. I discovered her when I became environment minister. As I looked up files and read more about the laws in India, I realised her stamp was everywhere. She was single-handedly responsible for the Wildlife Protection Act, Water Pollution Act and Project Tiger. She inherited her love for nature from her father, but when it came to ecology and environmental protection, she was a pioneer.”

In 1992, Ramesh notes, heads of 130 nations met at Rio to commemorate 20 years of the Stockholm meet, the first global meet on environment. But Indira was the only head of government (apart from Olaf Palme, the host) who had attended the Stockholm meet. She was ahead of her time.

There is her correspondence with the famous ornithologist Salim Ali, which, also reveal her sense of humour. In one letter she regrets how she can no longer go birdwatching―she attracts more stares than the birds. in her reply to Ali’s condolence letter over Sanjay Gandhi’s death, Indira goes on to discuss ecological issues. In another letter, this one to a young Priyanka Gandhi, she writes about a trip to the northeast. It’s unmistakably a letter from a grandmother. She writes about her visit to visit Itanagar, and cannot resist informing the child that it is the capital of Arunachal Pradesh.

Discovery of Indira: Jairam Ramesh | Sanajy Alawat

Discovery of Indira: Jairam Ramesh | Sanajy Alawat

Ramesh has got all his anecdotes from the written word (letters and some lesser known speeches), except one. Indira, along with Narasimha Rao and Ralph Buultjens, a Sri Lanka-born political scientist, was travelling from Bangalore to Mysore, with her giving a commentary on each tree that she could identify. When she stepped out to interact with the people waiting for her by the roadside, Rao muttered: ‘She should have been a botany teacher, not politician.’

“She created time to be concerned about the environment, and you can’t do that unless you feel for it,” says Ramesh. “The year 1971 marked the Bangladesh war, and she found time to make a new law on wildlife. In 1969, she was nationalising banks, and at the same time, reconstituting the Wildlife Board. She took unpopular decisions. The CPI(M) and the Congress wanted the hydel project at Silent Valley, but she saved it.”

The book would undoubtedly have been richer if it had the correspondence between Indira and her younger son, Sanjay Gandhi, who inherited her pro-environment genes. Ramesh, however, could not access it. Sanjay’s wife, Maneka, told him that the letters were consumed by termites.

Indira Gandhi: A Life in Nature

By Jairam Ramesh

Published by

Simon & Schuster India

Price Rs 799;

pages 448