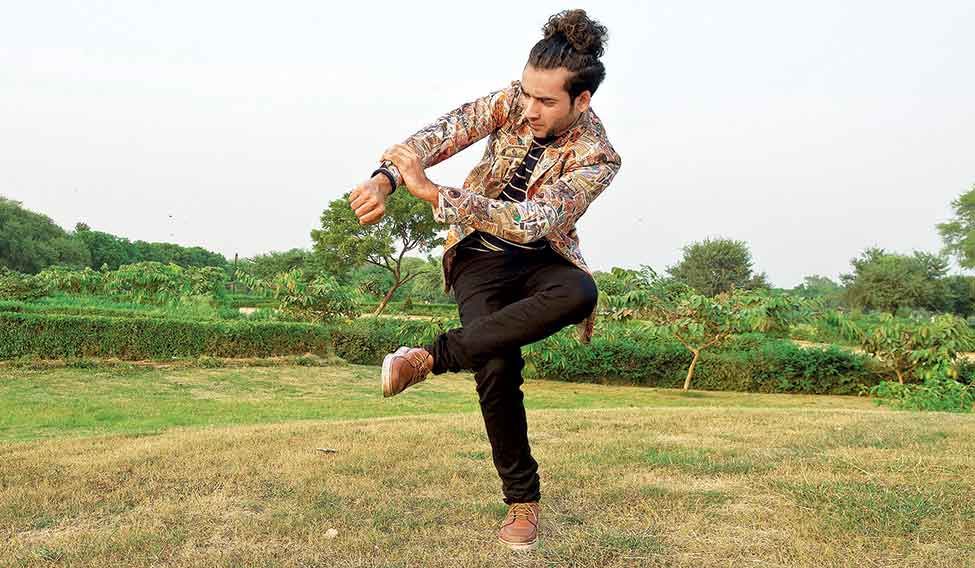

Bhupendra Singh lives in a nondescript apartment block in a colony in northwest Delhi—the kind you identify by its number, not by its looks. These days, however, a life-size poster outside the apartment makes things easy for those who come looking for his house. The poster shows Singh, aka the dancing sensation Poppin Ticko, with choreographer-director Remo D’Souza.

Ticko, 23, is a fixture in the ‘underground dance’ scene in India, a society of dancers who are averse to going mainstream. He first came into the limelight when he made it to the final of the dance reality show Dance+. With his unique dancing style and impressive moves, he is arguably the king of underground dance battles (UDBs). Part of the hip-hop movement, UDBs are covert events organised by underground dancers.

Step inside Ticko’s apartment block, and you hear the sound of hip-hop music drifting down the spiral staircase. A huge marigold garland rests on the railing that leads to his third-floor training room, where a group of youngsters are practising their moves for the next dance battle. “We want to be like you,” they say in chorus, before they leave for home. “Practise and practise, and you will,” replies Ticko.

What drives the craze for UDBs? “They are a great training platform to showcase talent and learn,” says Ticko. “A lot of credit for where I am today goes to the world of UDBs. In fact, the name Poppin Ticko was given to me by my UDB friends. I used to do popping and ticking dance forms very well, so they started calling me Poppin Ticko.”

Artistes like Ticko are passionate about conserving what they call pure dance forms. They focus on using them as a tool of self-expression, “so that original dance forms do not get corrupted by [those] making profit from it; we refrain from going public,” says Vikram Sehua, better known by his stage name BBoy Flexx. Part of the group called BeastMode Crew, Sehua organises a UDB event in Mumbai every year.

The information about UDBs and workshops and their schedule reach underground dancers and enthusiasts through text messages and social media platforms. “Group members have the liberty to bring their dance-loving friends along,” says Sehua.

Most UDBs are ticketed. Entry costs Rs.200 to Rs.300 for viewers. Competitors have to pay fees ranging from Rs.300 to Rs.500. The prize money, too, is not very high. It could be as little as Rs.3,000. “In some cases, the prize is just a pair of shoes,” says Ticko, laughing. “But it doesn’t matter because of the high you get by winning a competition where only professionals participate.”

Ticko, however, cautions that this approach will jeopardise the future of their secret society. “Unless underground dancers are able to earn handsomely, how are you going to sustain the movement of conserving pure dance forms?” he asks.

It is the reason that, despite criticism from the UDB community, Ticko ventured into the world of dance reality shows. “The idea is to create awareness about the world of underground dance among the masses,” he says. “It will help fetch hefty sponsorships for events and more money and respect for participants.”

Much like dance reality shows, participating in UDBs involves two competitors dancing impromptu to live DJ music in front of an audience of dance enthusiasts and a panel of judges (mainly national and international UDB veterans). “That is why no amount of practice ever seems enough to win the battle,” says Shashank Pallow, an underground dancer pursuing a bachelor’s degree in dental science.

The performer who wins the hearts of judges moves on to the next level and battles with another contestant. It could be a group or a single dancer. And the battle goes on like that till the winner is chosen.

Unlike in the case of dance reality shows, there are no chances of retakes or doing rehearsals. One cannot even choose the music to dance to. That is what makes UDBs so challenging. “You don’t know what is going to come your way,” says Sehua. “Besides, you have to compete with some of the best in their dance styles.”

If you thought the phenomenon of UDBs is restricted to metro cities, you are wrong. Sehua says thousands of such events happen every year across India. “What is fuelling this community is the availability of exemplary talent in our country and the growing internet penetration, which has broadened horizons, increased awareness about global dance forms and heightened the aspirations of young India,” says Sehua.

Meet Arif Chaudhary, aka B-Boy Flying Machine, who recently represented India at the Red Bull BC One Asia Pacific Final 2015 in Seoul, South Korea. “I have always wanted to perform on a global stage,” he says. “It feels like a dream come true for me. I want to make my country proud.”

Sensing the growing influence and popularity of UDBs in India and the talent of Indian underground dancers, international brands like Redbull, Reebok and Nike are increasingly seen sponsoring such events. “The events a brand sponsors reflects its personality,” says N. Chandramauli, chief executive officer of Trust Research Advisory, a data insight agency. “So, it makes perfect sense for brands who target the youth as their prime client base to enter into such tie-ups. It helps brands increase their reach and connect. Besides, these events are observatories, where they get to know what youngsters are doing these days.”