Shubhendu Sarkar of Hooghly in West Bengal was in for a rude shock when he enrolled at IIT Jodhpur in 2009. It took days for him to accept the fact that the institute was a far cry from the IITs he had seen and dreamt of. The academic block at IIT Jodhpur comprised just two buildings, rented from a nearby engineering college. The hostel was a fair distance away, and there was no facilities for extracurricular activities. Shubhendu had to while away breaks between classes chatting with friends or sitting in the library.

The faculty comprised ‘fresh PhDs’, and the labs were not up and running. He had to use the lab of the private college—that, too, was available on weekends only. “The situation improved when we were leaving, but for all of us who broke our backs for two years to land at an IIT, the world did come crashing down,” says Shubhendu, who now works in a Bengaluru-based company.

His experience points to the rot in IITs, which are no longer the preferred choice for many engineering aspirants. Take, for instance, Mrinalini, a class 12 student in Delhi who is set to take JEE (joint entrance examination) next year. Thanks to feedback from seniors, she has decided not to join newly launched IITs. “Good if I am able to get into one of the older IITs. But, if I don’t get a good rank, I would rather go to an NIT [National Institute of Technology] or a good private engineering college,” she says.

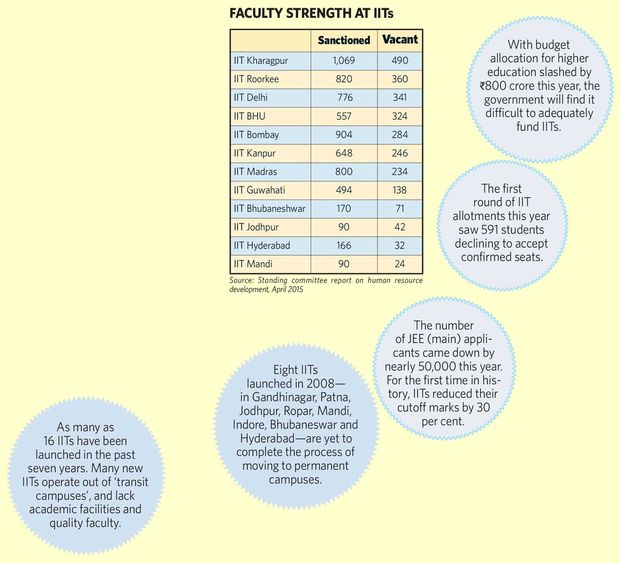

Once the most fancied technical institutes in the country, IITs are falling out of favour with students. According to the director of a prominent IIT, the first round of IIT allotments this year saw 591 students declining to accept confirmed seats. The number of applicants for JEE (main) came down by nearly 50,000 this year. And, for the first time in history, IITs reduced their cutoff marks by 30 per cent.

Most IIT directors, however, would rather not face the fact that IITs no longer captivate students. They say the large numbers of students who apply to IITs show that the confidence in the institutes is intact.

But they are missing two points. First, higher education in India is undergoing a massive change, thanks to quality private institutions coming up. Second is the growing allure of a wide variety of subjects, especially liberal arts, public policy and journalism. An increasing number of students do not want to go through the ordeal of spending two years preparing to enter IITs and four years studying there, only to land a job at an investment bank or an administrative role in the government.

“I feel that deep down, the questions of development, economics, history, society and culture are closer to my heart, as compared to questions of technology,” wrote Alankar Jain, who graduated last year from IIT Bombay, in Insight, a student-run magazine of the IIT. “We can’t be okay with so many of our students studying stuff they don’t care about.”

Apparently, only a third of IIT graduates choose careers in technology. While most IITs have departments for humanities and social sciences, they are too small to offer students a diverse set of courses.

The blot on the IIT brand owes a lot to new IITs. Even as eight IITs launched in 2008 struggle to stand on their feet, six more have been announced. Of the six, IIT Palakkad and IIT Tirupati will admit students this year onwards.

The IITs launched in 2008—in Gandhinagar, Patna, Jodhpur, Ropar, Mandi, Indore, Bhubaneswar and Hyderabad—are yet to complete the process of moving to permanent campuses. In most cases, state governments have allocated premises of existing engineering colleges or polytechnic institutes as ‘transit campuses’. But the space is too limited to house facilities for which IITs are known for—expansive research centres, state-of-the-art auditoriums, sports infrastructure and hostels.

For instance, professors at IIT Patna initially stayed in distant parts of the city, because of the unavailability of living quarters near the campus. MS and PhD classes at IIT Mandi are still held at its temporary campus, which is 25km away from the main campus at Kamand. Students have to travel to the main campus to access labs. A hotel near the transit campus has been converted into a hostel, as the main campus cannot accommodate all students. The main campus is still under construction. Thanks to the space constraint, a pile of lab equipment covered in plastic sheet lies outside a building.

Most new IITs are in the process of shifting to permanent campuses, but IIT Ropar and IIT Jodhpur are way behind schedule. Thanks to land acquisition issues, both the IITs will have to wait at least a year and a half to move to permanent campuses.

Construction costs have gone beyond estimates. A detailed project report for eight new IITs, prepared and approved in 2008, put the total cost at Rs6,080 crore. But thanks to delays, the cost has now escalated to Rs15,565 crore. “A permanent campus helps a lot in changing perceptions,” says Gautam Barua, director of IIT Guwahati. “Things will become better once these IITs move to their own campuses.”

Experts say an IIT should start functioning only after land approvals are in place. In the case of eight institutes launched in 2008, admissions began even before land was allocated to them. The government, it seems, has learnt a lesson. It has not approved IITs in Jammu and Kashmir, Goa and Karnataka, as the states are yet to clear land acquisition issues.

A new IIT brings its own set of challenges for a director. On his first day in office, Sarit K. Das, the newly appointed director of IIT Ropar, was surprised to see a stack of files on his table. They were leave applications awaiting his sanction. Usually, such applications go to department heads. But, with IIT Ropar being a new institute, Das had to deal with them.

A major challenge for new IITs is roping in quality faculty. Since most new IITs are miles away from metros, it is hard to recruit professors of repute. Most new institutes now have ‘fresh PhDs’ as associate professors. “Our young faculty is energetic and enthusiastic, but we need senior people to mentor them and to decide on the research strategy of a particular discipline,” says Das.

He and directors of other new IITs are trying to recruit retired faculty from older IITs. “We are persuading faculty from other IITs to join us. People generally don’t want to travel this far,” says Timothy A. Gonsalves, director of IIT Mandi.

A new IIT is usually mentored by an older, established IIT. The faculty from the mentor IIT engages with the new IIT for a few months. “After that, it starts waning. There have been days when there was no class because the faculty who was supposed to come from the mentor IIT did not turn up,” says the director of a new IIT.

Sarit K. Das | Arvind Jain

Sarit K. Das | Arvind Jain

IIT professors agree that India needs more technical colleges to keep pace with the rising number of students. But the question is: should all these colleges be IITs? And, even if they should be, is the pace at which IITs are announced justified? In the past seven years, as many as 16 IITs have been launched.

“No doubt, we need more quality institutes,” says R.K. Shevgaonkar, former director of IIT Delhi. “But the government should also look at the availability of inputs that go into building a great institute. Getting good faculty is an acute problem even for older IITs. The new ones will take at least ten years to stabilise.”

Experts say IITs have become a tool to get political mileage. “They have become a tag of pride, a prestige issue for every state,” says an IIT director.

“Government must decide whether they want to just open engineering colleges or create centres of excellence,” says M.K. Surappa, former director of IIT Ropar. “Mass opening of IITs is not desirable.”

A staggered approach is what experts suggest, plus a lot more time for new IITs to settle down before the government announces a new one. “They [the government] have bundled up a lot of them together,” says Aakash Chaudhary of Aakash Educational Services Pvt Ltd, which runs a chain of JEE coaching centres. “No new IIT came up for 30 years; they are probably compensating for that.”

Funding is a major problem for IITs; more so for the new ones, as they have to build everything from scratch. With the budget allocation for higher education slashed by Rs800 crore this year, the government will find it difficult to adequately fund IITs.

Experts say reckless expansion has hurt the IIT brand. According to executive search firm EMA Partners, only 28 per cent of CEOs of top 200 Indian companies had IIT or IIM qualification. In 2009, half of India’s CEOs had IIT or IIM degrees. “The brand has been diluted because of new institutes. Recruiters will now look for a specific established IIT, say Delhi or Bombay, rather than going by generic IIT tag,” says K. Sudarshan, regional managing partner, Asia, at EMA Partners.

“The government has done a terrible job of cloning IITs. They lack the calibre to build high-quality technical institutions,” says Zishaan Hayath, founder of Toppr.com and IIT Bombay alumnus.

Making matters worse is political meddling. Though autonomous by statute, IITs have long been victims of government interference. IIT directors are not pleased with Human Resources Minister Smriti Irani, who is known to have a domineering attitude. Apparently, at one of the IIT council meetings, an IIT director was made to apologise for a petty matter.

Right now, however, the most pressing issue for IITs seems to be the quality of students, which, professors say, has declined. “Coaching classes are beating the system,” says Das. “IITs have failed to tap raw talent. We get the best coached people; not necessarily the best people.”