Kochi Metro was opened to the public on the dawn of June 19. By the time dusk fell, more than 62,000 tickets had been sold, generating Rs 20,42,720. It was not the money that counted, though. It was the footfalls. Going by the number of tickets sold on the first day and the long queues outside several stations, a number equivalent to roughly 20 per cent of the city’s population had turned up to buy the tickets. A Bollywood blockbuster could not have opened better.

For most riders, it really was akin to a trip to the movies. They were not commuting; they were just there to check out whether Kochi’s most hyped infrastructure project was worth the buzz. The consensus seemed to be that it was.

The honeymoon will not last long, though. The 13-kilometre stretch that has been opened to the public only serves a fraction of the project’s potential beneficiaries. It runs southwards from Aluva, 27km north of Kochi, to Palarivattom, which is just outside the area that can be called the heart of the city. The viaduct that runs further south, through the city, has not been completed. At its southernmost point, construction has not even begun. For now, Kochi Metro is quite like the Bandra-Worli Sea Link—without, well, the link.

The thrill of joyriders would soon start to wear thin, and nobody knows it better than Kochi Metro Rail Ltd’s managing director Elias George. He knows that KMRL needs to do more than just operationalise the viaduct to attract more people to the transit system. “Kochi is coming up like Bangalore [in terms of traffic],” he says. “It’s complete deadlock. You can’t go from one place to another without getting stuck. The roads are completely choked. So, what we are trying to do….”

… is truly interesting.

To understand the plan, you have to know Kochi. It is not like the other seven metropolises where metro rail projects have come up or are under construction. At least a dozen islands are scattered along mainland Kochi’s long coastline, which is torn asunder by waterbodies of various sizes—from backwaters and rivers to creeks and canals.

Apart from geography, there is the matter of population. Kochi’s city-area population is just under 6,00,000, while its metropolitan area (which includes the surrounding urban regions) has two million people. Among Indian cities, that is one of the most skewed city-metropolitan population ratio. (Bengaluru, for instance, has a city-area population of 8.42 million and a metropolitan area population of 8.52 million.) Imagine the rush when a million people—on bikes and cars, buses and boats—scramble in and out of their workplaces in a city where vehicles outnumber households.

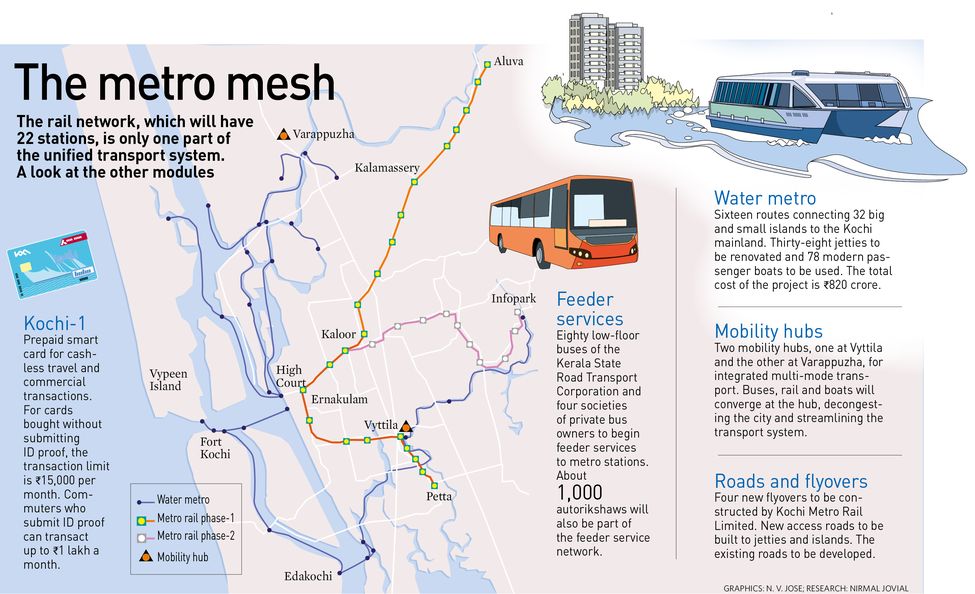

It is clear that Kochi Metro alone cannot solve the problem. “So, what we are trying to do is to make Kochi the first city in India where the public transport system is integrated, so that people leave their cars at home and find public transport a pleasant experience,” says Elias George. “We are going to unify the timetable—the metro reaches Aluva at 10.30, the bus starts at 10.35, and the boat, and so on. We are going to unify the ticketing, too. The management is also going to be made common.”

The plan is to bring at least half a dozen stakeholders—from private bus owners to state-owned corporations that run road and inland waterway transport networks—under a single, powerful organisation called Unified Metropolitan Transportation Authority, which will be responsible for planning and operating Kochi’s entire public transport system. It is a Herculean task, but KMRL is up to it.

“For this purpose, we have made a draft UMTA bill,” he says. The bill, if passed, would enable UMTA to bring in sweeping reforms that would make public transport seamless. KMRL has already launched a prepaid smart card, called Kochi-1, which can be used to pay for a metro ride. As UMTA takes wing, commuters can use it on buses and ferries. A smartphone app of the same name will help plan journeys, too. “What we are hoping is that, in a couple of months, all this will be integrated,” says George.

Perhaps, the biggest hurdle has already been crossed. Private bus owners, who are often accused of chasing profits recklessly, but still play a significant role in Kochi’s public transport system, have floated four societies to begin and operate feeder services in accordance with KMRL guidelines. “There will be no malsarayottam [reckless driving], because they [private bus owners] will share the profit and loss…. They are the ones that are the keenest to join the project,” says George.

Going green: Elias George at the launch of KMRL’s bike-sharing initiative, which allows commuters to use bicycles free of cost to cover distances within city limits.

Going green: Elias George at the launch of KMRL’s bike-sharing initiative, which allows commuters to use bicycles free of cost to cover distances within city limits.

It does help that KMRL enjoys immense goodwill. But that was not the case five years ago, when construction began and nearly everyone was up in arms, from landowners who said the compensation was inadequate to commercial establishments that feared a dip in business. All that changed because of KMRL’s nimble, surefooted moves. “A lot of our ideas—like the motifs you see [at stations] and the bike-sharing initiative—came from the youngsters in our team,” says George. “We are like a startup, and that has been a great plus for us.”

That, and the association E. Sreedharan has had with the project. As adviser to Delhi Metro Rail Corporation, Sreedharan played a key role in ensuring that the implementation was smooth. “It’s been a pleasure working with him,” says George. “One, he is India’s most outstanding project manager. Two, his reputation is like a big aal maram [banyan tree]… [For a project like this] a lot of permissions are required from different agencies. Because of his great reputation, nobody dared stand in the way of the Kochi Metro project.”

George comes across as modest about his own feats. Those in the know say that the ‘water metro’ project, which will provide connectivity for those living outside the mainland and along the backwaters, is his brainchild. The project is expected to improve transport in areas that are perceived to be less developed than the mainland. “Since my childhood days, I have been seeing the potential of the Kochi backwaters. Water transport is the cheapest and the most eco-friendly mode of transport. The water metro will help poor communities living along the backwaters.”

It helps that George, 60, knows Kochi like the back of his hand, and loves it for what it is. “You know why I stay down in Kochi when my family is in Delhi?” he says. (His wife, Aruna Sundararajan, is IT and telecom secretary in New Delhi.) “I choose to stay alone in Kochi because, the way I see it, Kochi is one of the most unique cities in the world. If you could get two things right—transport and waste disposal—it would become so much better.”