A 3.1kg baby boy's birth in Jaslok Hospital in Mumbai on March 7 made headlines, just like his mother's did on August 6, 1986. For he was born to 29-year-old Harsha Chawda Shah, India’s first documented case of in vitro fertilisation (IVF) baby. What made his birth more special was that the same set of doctors—Dr Indira Hinduja and Dr Kusum Zaveri—who delivered his mother also delivered him. Born on Mahashivratri, the baby is God's gift, says Shah, while recovering from the C-section she underwent because the baby had turned in the breech position close to birth.

For the two doctors, Shah's baby brought back memories of their trials and triumph 30 years ago. Hinduja was then working in the civic body-run King Edward Memorial (KEM) Hospital in the obstetrics and gynaecology department. In July 1978, Dr Robert Edwards and Dr Patrick Steptoe gave the world its first test tube baby, Louise Brown, in Britain, and Hinduja wanted to do the same in India. She sought the help of Zaveri, her long-time colleague. To try IVF in a municipal hospital then was no easy feat. There were multiple challenges but the duo persevered with their passion and focus. “I am proud that we succeeded in creating the first documented case of a test tube baby when we had no prior experience,” says Hinduja. “We didn’t go abroad to learn the technique, and we did it when we both were working full time, by trial and error.”

Hinduja'a baby project began in 1984 at the National Institute for Research in Reproductive Health, located opposite the hospital. She first experimented with hamster eggs and gradually mastered the technique. She then sought the approval of the scientific and ethics committees of the hospital and the NIRRH to try it on patients.

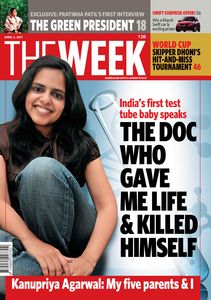

THE WEEK featured Kanupriya Agarwal in its issue dated April 3, 2011.

THE WEEK featured Kanupriya Agarwal in its issue dated April 3, 2011.

In the IVF procedure, a woman is given a hormone to produce more than one egg in the uterus. When the eggs mature, the fluid is retrieved from the uterus and incubated in a special liquid. The eggs are then fertilised with the partner’s sperms in an incubator. The fertilised egg is called an embryo, which is cultured in the lab for two to six days. The embryo is then transferred to the uterus, where it is expected to implant and lead to pregnancy.

The hospital, however, did not have laparoscopic equipment. Nor did it have transvaginal ultrasound to view the eggs. There were no incubators either. Zaveri brought her own laparoscopic equipment and Hinduja used it to retrieve the eggs. But with no monitor to show the images, they would pray that the fluid they had retrieved had the eggs, each with a diameter of hundred microns, one hundredth the size of a small point made by a ball pen. “We didn’t know how a human egg looked. We would refer to the hamster egg to identify it,” says Hinduja.

The fluid retrieval was a tricky and time-consuming process. With a single operating theatre, which was shared by six departments, the department heads would often complain against them to the dean. So, Hinduja would come in early morning, waking up the ward boy and anaesthesiologist, to start work on the procedure. Once, the incubator broke down, and the only technician who could repair it had gone out to watch a movie. As the eggs couldn't be kept out for long, the doctors immediately went to the movie theatre and brought him back to the NIRRH building to fix the machine.

Harsha Chawda Shah's mother, Maniben Chawda, was a municipal worker. Tuberculosis had blocked her fallopian tubes and, therefore, she had trouble conceiving. After Hinduja explained the IVF procedure, she agreed to the experiment. She conceived in the first attempt itself, and the news reached Hinduja on her birthday. An international conference was on in the hospital at the same time. “We were so excited that we announced the news of the pregnancy in the conference,” says Zaveri, who had by then started working with the Family Planning Association of India. But Hinduja still asked her to assist in the caesarian delivery. “When I reached the operation theatre, I couldn’t get in because of the crowd of doctors and nurses around the theatre,” recalls Zaveri. And thus, they delivered India’s first documented IVF baby—Dr Subhash Mukhopadhyay, who had delivered India's first test tube baby in 1978, didn’t get due recognition until 2002.

The two doctors continue to work together and have delivered more than 15,000 babies through IVF. “We are good friends but we also fight like cats and dogs,” says Hinduja, who received a PhD for her original work in IVF. Winner of multiple awards, she also pioneered the Gamete Intrafallopian Transfer procedure in India, and is credited with developing oocyte donation technique for menopausal and premature ovarian failure patients.

Shah, who calls Hinduja her second mom, remained a special baby for the doctors; they were part of many of her birthdays and celebrations. “We should search on the internet whether we are the only ones who delivered the IVF baby and also her baby,” says Hinduja. “Of course, I don’t want to live that long to see if I deliver this boy’s baby also.”

Testing times

KANUPRIYA AGARWAL alias Durga was born on October 3, 1978. Though she was India's first test tube baby, she was recognised so only in 2002 when the Indian Council of Medical Research recognised Dr Subhash Mukhopadhyay's work.

A physician, Mukhopadhyay had combined in vitro fertilisation and cryopreservation of human embryos—the most preferred technique today—to develop the first test tube baby. But the recognition came too late; he committed suicide in 1981 after the West Bengal government denounced his claims of creating the first test tube baby.