Too much sugar could cause diabetes. Too much sugar, in India, causes suicides. India's sugar output has been rising in the past six years and a record production is expected this year. The surplus, however, brings no joy to farmers, and many have taken their lives to end their misery.

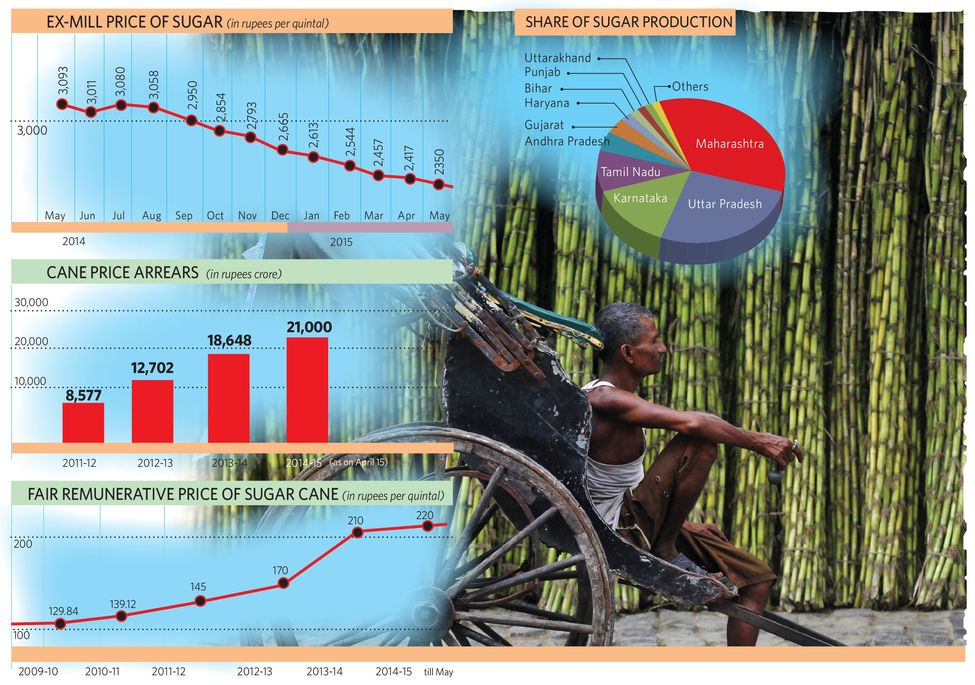

The problem: the Union and state governments fix the price at which farmers sell sugarcane to mills. The selling price of processed sugar, however, is market controlled. Recently, the market price of sugar dipped, causing huge losses to mills. Citing this loss, mills held off on paying farmers for their produce.

On June 25, Ninge Gowda, a 65-year-old farmer from Mandya district of Karnataka, set his fields on fire and walked into the inferno to end his life. He had taken a loan of 02 lakh from private moneylenders, but could not repay them as the sugar mill refused to buy his produce. Karnataka, like many other states, has created 'command areas' for each sugar mill, which means farmers in that area can only sell to that mill. “On paper, mills must continue the crushing season till the last stick of sugarcane has been used. But the real situation is often different,” said Vrinda Sarup, secretary, department of food and public distribution.

As farmers protested throughout the state, Chief Minister Siddaramaiah said a glut in the market had led to a crash in sugar prices. He appealed to the farmers not to end their lives and assured compensation to Gowda's widow, Boramma, and his paraplegic son, Eere. “The area under sugarcane cultivation has doubled,” he said. “It is now grown in 17 lakh acres and sugar production has touched 49 lakh metric tonnes. We are committed to resolving the crisis.”

A spate of suicides, 50 in the past five months, have rocked the Karnataka assembly. And, mill owners are yet to pay dues of 0960 crore, accrued over the last two seasons, to farmers. “Farmers are cheated at every step,” said Jagadish Shettar, leader of opposition in the assembly. “The sugar mills undervalue the quantity of cane supplied to the mills by manipulating the weigh bridges. It accounts for a loss of 10 per cent. Then, the base price fixed by the government is not adhered to. The mills don’t settle the bills within the stipulated 14-day period. Yet, no single case has been booked against any of these mills.” A majority of the 60-odd sugar mills in the state are owned by MLAs, ministers and politicians. This, perhaps, explains the government's reluctance to take action.

According to official sources, sugar output in 2014-2015 would be about 2.8 crore tonnes. “We will be left with a surplus of 40 lakh tonnes over and above the 50 to 60 lakh tonnes we keep as reserve stock. Even at Rs30 a kg, Rs12,000 crore is stuck in stock,” said Abinash Verma, director-general of the Indian Sugar Mills Association.

As the area under sugarcane cultivation grew, so did the arrears owed to farmers. In April, the figure stood at Rs21,000 crore in the sugar-producing states. Of this, Rs12,000 crore was owed to farmers in Uttar Pradesh. The state has also seen many suicides over the years. Two years ago, Satyapal Singh, a 45-year-old sugarcane farmer of Bastauli village, said in his suicide note that he had lost all hope of getting his arrears of Rs40,000.

A month ago, the Allahabad High Court directed the sugar mills to clear 75 per cent of these arrears by July 15. “It is quite unlikely to happen,” said Bharatiya Kissan Union spokesman Rakesh Tikait. “Both the Union and state governments are responsible for the plight of the farmers. The Union government makes unfriendly policies while the state government fails at the implementation level.”

Graphics: Deni Lal; Photo: Reuters

Graphics: Deni Lal; Photo: Reuters

Adding to farmers' woes is the system of under weighing, which can cut payments by up to 10 per cent. In Uttar Pradesh, there is an informal understanding between the mills and farmers. Said Manjit Singh, a sugarcane farmer in Shahjahanpur: “The mills weigh 10 per cent less for every 1,000 quintals, causing a monetary loss of about Rs35,000 to the farmers.” Apparently, this has become an accepted practice as farmers are dependent on the mills.

The problem of pricing is also a cause for concern. Farmers in UP have been demanding between Rs325 to Rs350 a quintal for their produce, while mill owners want the price to be fixed at about Rs225. However, the state advised price (SAP), which is over and above the Union government's fair and remunerative price (FRP), is Rs280.

“Most states take populist measures and increase the SAP as they see it as a favour to farmers. We have asked states to do away with the SAP system and stick to FRP as cost of sugar production has increased considerably because of the higher cane prices,” said Kallappa Baburao Awade, president of National Federation of Cooperative Sugar Factories Limited.

In Maharashtra's Vashi sugar market, a quintal of sugar costs about Rs2,000 to Rs2,100, while production cost is Rs2,930. In Uttar Pradesh, ex-mill sugar prices were Rs2,300 to Rs2,400 a quintal in June, while cost of production was Rs3,200.

Pawan Kumar, president of South India Sugar Mills Association said the sugar mills, too, were desperate and were ready to face any government action. “There is a huge pile up of sugar stocks and the sugar price has crashed globally. The fair remunerative price is not being fixed based on the market price of sugar,” he said.

Raju Shetti, MP and founder of Swabhimani Shetkari Sanghatana, a farmers' union in Maharashtra, said the low import duty on sugar (25 per cent) caused domestic prices to plummet. “After repeated requests and number of meetings with the chief minister and Union commerce minister, the import duty on sugar was increased to 40 per cent,” he said.

Though this stabilised the domestic prices, many mills had, by then, sold in distress and it reflected in the losses. Some mills in western Maharashtra could only pay Rs1,500 for a tonne of sugarcane while a few in Pune paid Rs1,800. “That is way below our production cost. Until this year, sugarcane was the only commodity that yielded marginal profit for us. But now, we are in total loss,” said Shivaji Patil, a farmer from Niphad in Nashik district. “These leaders were making us agitate for Rs3,000 a tonne when the factories were paying Rs2,300 and the FRP was Rs1,900. Now, as they are part of the NDA, they are keeping mum.”

Kodihalli Chandrashekhar, president of Karnataka Rajya Raitha Sangha, a farmers' union, said: “We dare the government to arrest all of us. Sealing the factories or seizing sugar stocks is no solution. The government must act against sugar mills and ensure the farmers are paid their dues.”

On June 29, sugarcane farmers confronted Chandrakant Patil, Maharashtra minister for cooperation, after he addressed BJP workers in Solapur. Demanding that he order sugar factories to release the overdue payment, a few farmers surrounded his car and, almost immediately, the police started a ruthless lathi-charge.

Patil had earlier warned the sugar factories that the government would seize their stocks in the event of non-payment of FRP and would initiate criminal proceedings against the directors.

In 2007, when sugar stocks were almost as high as now, the government had averted the crisis by creating a buffer stock of 50 lakh tonnes for public distribution and had allowed export subsidy on 60 lakh tonnes. The industry is now awaiting such steps from the Narendra Modi government.

“The sale side of sugar has been decontrolled totally and sugar prices are being market discovered,” said Narendra Murkumbi, managing director of Shree Renuka Sugars Limited. “However, the price of raw materials, which accounts for 72 per cent of our costs, is determined by the government. This mismatch is the basic problem which is making sugar production an unviable business in the country.”

A total decontrol of the sugar sector is seen as a solution to the crisis. The government has, for some years, been planning to set up a sugar price stabilisation fund. “This fund would be the source of subsidy to farmers during the downswings faced by the industry,” said a recent report of the Commission of Agricultural Costs and Prices.

“We are optimistic that government will find a long-term solution to the current crisis as it is only in crisis that the government takes important policy decisions,” said Abinash Verma.