In December 2015, a hunting party from Qatar arrived at a hunting zone in Iraq’s Muthanna province, 370km southeast of Baghdad. The Iraqi government had assured them that the game reserve was safe. The 26-member group included members from the ruling family. They were, however, kidnapped by Kata’eb Hezbollah, a Shia militant group backed by Iran. Last April, Qatar made a deal with Iran and several militant groups for their release. It apparently involved a huge payout to Iran and the militants, and population swaps involving four villages in Syria. Though Qatar denied that any ransom was paid, its ambassador to Iraq and an emissary of the emir flew to Baghdad on April 15, with 23 sacks full of currencies, worth half a billion dollars. Six days later, the hostages were set free. The payout to Iran angered Saudi Arabia to no end.

About a month later, on May 24, two days after Donald Trump’s visit to Saudi Arabia, official Qatari websites carried reports criticising the US president, praising Iran, reaffirming Qatar’s friendly ties with Israel and warning about recalling its ambassadors from Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Egypt. Qatar denied the reports and said the websites were hacked. Saudi Arabia and the UAE, however, repeated the reports and blocked Qatari media, effectively blacking out the official denial.

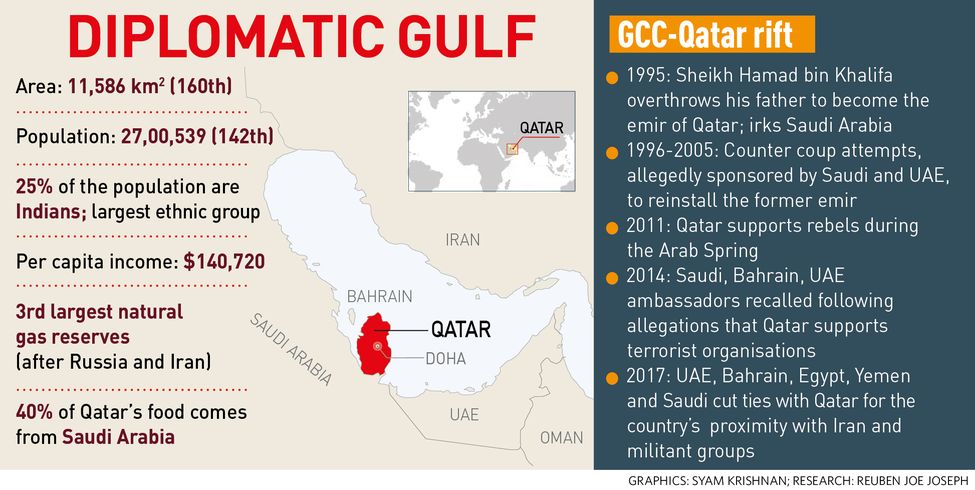

On June 5, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain and Egypt announced the decision to cut off all diplomatic ties with Qatar, suspend all land, sea and air transport, eject Qataris from their countries and recall their citizens from Qatar. They disallowed Qatari planes to fly over their territories and banned Qatari vessels from their ports. The next day they were joined by the Maldives and the factional governments in Yemen and Libya. The Saudi-led group accused Qatar of backing radical islamist groups like the Muslim Brotherhood.

Qatar has always been a maverick in the otherwise staid and status quoist Gulf region. It was involved in a running feud with Bahrain over territorial issues for nearly a century until 2001. It got into a border skirmish with Saudi Arabia, its only land neighbour, in 1992, leading to the death of three people. The roots of the current showdown, however, lie in the 1995 coup in Qatar in which Hamad bin Khalifa al Thani took over as emir, replacing his father, Khalifa bin Hamad. The Saudis staunchly opposed the coup, and there were two unsuccessful counter coup attempts—in 1996 and in 2005—to reinstate Khalifa, which the Qataris alleged were backed by Saudi Arabia. Suspecting collusion with the Saudis and the Emiratis, Qatar stripped off citizenship of more than 5,000 members of the Bani Murra tribe, who live on the border.

Hamad pursued an independent foreign policy unlike his father who had followed Saudi Arabia’s lead in foreign affairs. In this, Hamad had the support of his foreign minister Hamad bin Jassim. Several Arab regimes like Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Egypt consider the Muslim Brotherhood, perhaps the largest Islamic organisation in the world, to be a terrorist outfit, but Hamad developed friendly ties with it. He actively supported the Brotherhood during the Arab Spring revolution in Egypt and, subsequently the Brotherhood government headed by Mohammed Morsi, which replaced the dictatorship of Hosni Mubarak.

Raging fire: Muslim Brotherhood activists in Cairo protesting the ouster of former president Mohammed Morsi. Qatar’s support to the Brotherhood has caused a breakdown in its ties with Egypt | AP

Raging fire: Muslim Brotherhood activists in Cairo protesting the ouster of former president Mohammed Morsi. Qatar’s support to the Brotherhood has caused a breakdown in its ties with Egypt | AP

The Qataris, however, had to beat a hasty retreat from Cairo after the Egyptian military deposed Morsi and took power under the leadership of its chief Abdel Fattah el-Sisi. Qatar has also been an active sponsor of Hamas, the Palestinian militant organisation that rules Gaza, while Saudi Arabia has always preferred to do business with the more moderate Fatah faction headed by Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas.

Qatar’s decision to chart an independent policy was backed by the financial heft it commanded by developing its huge natural gas reserves. Worried about the impact it would have on his largely conservative country, Khalifa had been reluctant to exploit the reserves. Hamad reversed this decision and joined hands with Iran to develop South Pars, the world’s largest gas field. It soon made Qatar the world’s largest exporter of natural gas, turning it into one of the wealthiest countries in the world.

The development affected Qatar in two profound ways, says Joshy M. Paul, who teaches international relations at Christ University, Bengaluru. “It developed close ties with Iran, the sworn enemy of Saudi Arabia. Second, it gave Qatar the power and confidence to step completely out of the Saudi sphere of influence. It gave Qatar a wide berth to formulate its own policies, and the guts to punch above its weight in international relations.” The wealth also helped Qatar to win the bid to host the 2022 FIFA World Cup and buy stakes in a large number of iconic institutions, commercial establishments and prime real estate across the world.

Qatar used its considerable wealth to launch Al Jazeera, a satellite news channel which telecast both in English and Arabic. It brought about a revolution in the Middle East as the channel dealt with topics which were hitherto taboo. In 2002, it telecast a story critical of the Saudi royal family, which angered the Saudis so much so that they recalled their ambassador to Doha and chose not to have high level representation in Qatar for five years.

Resentment against Qatar has been brewing in several Arab capitals for the past few years. There were hopes that ties would improve after Hamad abdicated in 2013 in favour of his son Tamim. Yet, a few months into Tamim’s rule, the situation worsened, and in March 2014, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain and the UAE recalled their ambassadors from Qatar. The crisis was resolved only after Qatar made some concessions including a guarantee of toeing the GCC line on foreign and security issues, expelling certain key Brotherhood leaders and shutting down Al Jazeera offices in Egypt.

Apart from such irritants, the symbolism of Trump choosing Saudi Arabia as his first destination abroad as president and his unprecedented support to Saudi positions on nearly all matters of global and regional importance perhaps emboldened the Saudis to target Qatar. Observers also see the hand of Mohammad bin Salman, the Saudi deputy crown prince, and Mohammad bin Zayed, the UAE crown prince, in the latest developments. “The 31-year-old Mohammad bin Salman wants to be the king of Saudi Arabia,” said A.K. Pasha, who heads the Gulf Studies Programme at Jawaharlal Nehru University, Delhi. “And, the present crisis is possibly its fallout. The visit by Trump is another important reason.”

There was some panic among the Qataris after as news of the blockade spread. A long-time Indian expat from Doha told THE WEEK that the supermarkets were so crowded on June 5 that she could not even find a shopping cart. And, her favourite brand of dairy products, which used to come from Saudi Arabia, was missing from the shelves.

A day later, however, things were back to normal. “Not much has changed on the ground here,” said Sandeep, an Indian who works for a leading multinational company in Qatar. He said the government asked the people not to panic and sent out messages in English and Hindi to reassure them. “The only real impact has been that holiday plans of many have been affected because of flight cancellations.” But if the blockade continues indefinitely, it could become a matter of serious concern.

Veteran diplomat M.K. Bhadrakumar said the travel ban could hurt Indians. “The denial of air space to Qatar Airways will mean re-rerouting of flights to India and resorting to circuitous routes overflying Iran and so on. The cost of air travel may increase,” he said. On the diplomatic front, India said there was no challenge arising out of the situation. “This is an internal matter of the GCC,” said External Affairs Minister Sushma Swaraj.

Efforts of reconciliation are already on to bring an end to the crisis. Kuwaiti ruler Sheikh Sabah Al-Ahmed travelled to Riyadh on June 6 to meet Saudi King Salman. He had also asked Sheikh Tamim to postpone a speech he was expected to deliver on the same day. During earlier Qatar-Saudi spats, Kuwait had played a key role in brokering peace. Oman has also stepped up diplomatic initiatives. Many other countries including Turkey and Sudan have offered to mediate.

But Saudi Arabia and the UAE have stepped up pressure and said relations would not be restored until Qatar broke all links with the Muslim Brotherhood, Hamas and Iran. The UAE has threatened anyone publishing expressions of sympathy towards Qatar with 15 years of imprisonment and barred entry to Qatari citizens and resident visa holders.

If Qatar is unrelenting, it is likely to aggravate the crisis and could even lead to demands of a regime change. “The Saudi intention remains unclear,” said Bhadrakumar. “Is it to get Qatar to capitulate on links with Muslim Brotherhood or is it regime change? Will Saudi Arabia invade Qatar to overthrow the regime or will it simply engineer a coup? Of course, in the latter case, there could be turmoil with much economic dislocation and security implications.” The already fragile situation in the region turned even more fluid on June 7 following attacks in Iran, targeting its parliament and the mausoleum of Ayatollah Khomeini. Islamic State has claimed responsibility for the attacks, which took 12 lives.

The United States holds the key in ensuring that the situation does not get out of hand. After a few initial tweets in which he was seen to be giving his imprimatur to the Saudi offensive, Trump called King Salman and told him that unity in Gulf was important “for peace and security in the region”. The US operates one of its largest military bases in Qatar, and ExxonMobil, which was previously run by Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, has extensive interests in the country.

Trump’s latest call has led many observers to believe that the crisis may not linger on. And, on June 7, came reports that it was the Russians who had hacked the Qatari websites on May 24. The American FBI confirmed the hacking. US and Qatari officials said the Russians were trying to create a rift among the US and its allies.

Qatar, however, will have to make major concessions for a reconciliation. “Qatar has no option but to capitulate,” said Bhadrakumar. “The Saudis have much clout with the Trump administration.”