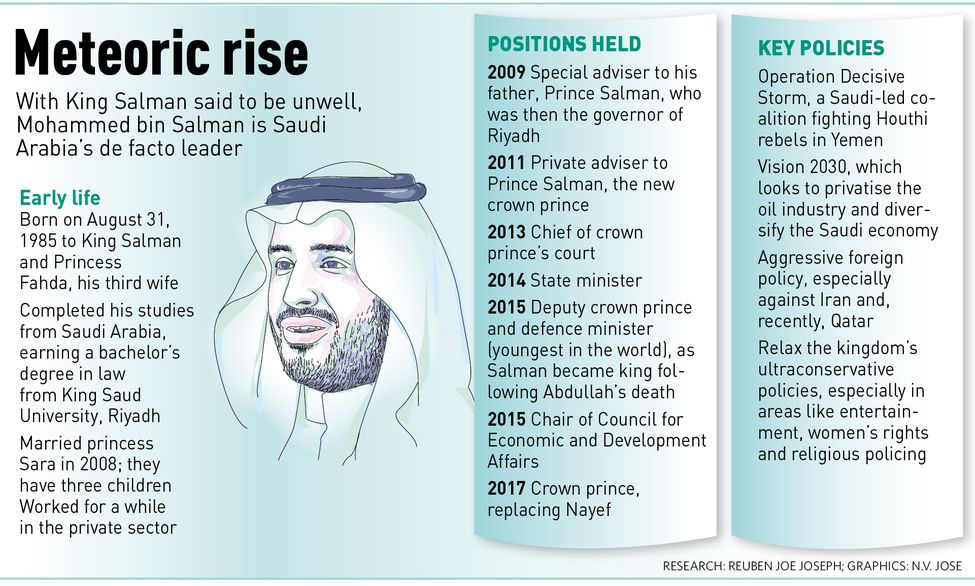

Two years ago, during a vacation at a seaside resort in the south of France, Prince Mohammed bin Salman (MbS) spotted Serene. The luxury yacht, built by the Italian shipbuilding company Fincantieri, was owned by Yuri Shefler, the Russian liquor tycoon famous for the Stolichnaya brand of vodka. MbS offered Shefler $550 million for the yacht, bought in 2011 for $330 million. The deal was concluded the same day. The swift transaction captures the personality of MbS, who was appointed the crown prince of Saudi Arabia by his father King Salman on June 21. The presumptive heir to the Saudi throne is forceful, and decisive.

For those following the byzantine intrigues of Saudi politics, the news came as no surprise. The rise of MbS was meteoric after his father became king in January 2015, following the death of king Abdullah. He was soon given the charge of the defence ministry and the royal court, and was made the deputy crown prince. Although Salman had appointed his brother Muqrin as crown prince and later his nephew and interior minister Muhammad bin Nayef to the post, it was clear that he wanted the 31-year-old MbS to succeed him. So, Nayef, the counterterrorism czar, who kept Saudi Arabia safe for several years and enjoyed excellent ties with the US administration and intelligence agencies, was systematically sidelined.

MbS was given the charge of the national oil behemoth Aramco, and was chosen to accompany his father to meet president Barack Obama in the US. He represented his country in the G-20 summit in China last year. It made The New York Times observe last October: “His [Mohammed bin Salman’s] seemingly boundless ambitions have led many... to suspect that his ultimate goal is not just to transform the kingdom, but to shove aside the current crown prince... to become the next king.” What happened on June 21 was perhaps the penultimate step of that mission.

Yet, when the decision came, it upended norms in the ultraconservative royal family. It was for the first time that the possibility of handing over the reins to the next generation of Al Sauds has become real. Since the inception of the modern kingdom in 1932, power was always wielded by the founding king Abdulaziz and his sons.

MbS has always been his father’s favourite, although his other sons were more illustrious. His second son Sultan was an astronaut, who famously shared cabin space with a female American crew member on the space shuttle Discovery, more than three decades ago. His fifth son Faisal has a doctorate from Oxford and is the governor of Madinah province. MbS was educated locally, earning a bachelor’s degree in law from King Saud University, Riyadh. But he had the advantage of being born to his father’s third and favourite wife, Princess Fahda, and he grew up in the same house as his father, unlike his siblings, who were raised by their mothers.

Joseph A. Kechichian

Joseph A. Kechichian

Although the elevation of MbS was expected, its timing was not. Some observers point to an American connection to explain the unexpected announcement. “The immediate reason is Donald Trump and his blessings,” said Gulshan Dietl, an expert on Saudi Arabian politics at the Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, Delhi. Salman’s announcement came exactly a month after Trump’s visit to Saudi Arabia. “The American role should be understood from two angles,” said Joshy M. Paul, international relations expert at Christ University, Bengaluru. “One, it can be seen as a reward to MbS, who King Salman believes brought life back into US-Saudi relations after a disastrous phase while Barack Obama was president. His successful visit to Washington in March and Trump’s decision to make Saudi Arabia his first overseas destination as president were acknowledged by the king as his son’s achievement. Two, the Trump family’s wholehearted support of MbS emboldened the king to pension off his nephew, who was an Obama favourite, and install his son.”

In March, Trump held a formal meeting with him in the Oval Office and hosted a lunch in his honour in the State Dining Room. MbS also dined with Trump’s daughter Ivanka and her husband, Jared Kushner, during the visit. When Trump came to Saudi Arabia in May, MbS hosted a dinner for the Kushners at his palace. Within hours of the elevation, MbS received a congratulatory phone call from Trump.

Not everyone agrees with the American theory, though. Joseph A. Kechichian, senior fellow at the King Faisal Centre for Research and Islamic Studies in Riyadh, told me that it was easy to assume that the US played a role in every development in any country. “That is often wishful thinking, and, in 98 per cent of all cases, incorrect,” said the American scholar, whom I had accompanied on a trip to the Taj Mahal, nearly a decade ago. Kechichian, who has extensive contacts within the Saudi royal family, said the succession issue was purely a Saudi decision. “It was the writ of a single man, King Salman.”

It may not be an easy task. In fact, the royal decree issued to appoint MbS as crown prince made a change to the Saudi Basic Laws that in future, the king and the crown prince could not be from the same branch of the royal family. And, Salman has ensured that the post of the interior minister, taken away from Nayef, will stay within the same branch of the family. Still, in the Allegiance Council, comprising the sons and prominent grandsons of the founding king, which voted to nominate the new crown prince, there were three holdouts against MbS. There are a number of disgruntled senior princes now joined by Nayef, who no longer have a chance to rule—Muqrin, former king Abdullah’s son Miteb and former crown prince Sultan’s son Khalid. Salman and MbS will have to handle the situation deftly to prevent the situation getting out of hand.

Kechichian said the royal family was likely to stay together. “All Al Saud members place the interests of the family above everything else,” he said. “Some of the older members might express verbal disapproval, but that would be the extent of their complaints.” A.K. Pasha, director of the Gulf Studies programme at Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, also ruled out any immediate crisis within the ruling family. He, however, warned that “simmering tensions would come to the surface if the going gets tough in Yemen and Qatar.

These two countries have already become major foreign policy embarrassments for Saudi Arabia, especially MbS, who seems to be driving an aggressive Saudi posture. In what is clearly a proxy war against its Shia rival Iran, Saudi Arabia is fighting the Houthi rebels in Yemen since 2015 on behalf of the ousted president Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi. It has, however, failed to make any headway, but has resulted in a growing humanitarian crisis in the impoverished country, putting a question mark on Saudi defence capabilities despite spending billions of dollars in arms.

In the Qatari crisis, too, most observers see the hand of MbS. Pasha told THE WEEK in June that it was precipitated by the attempts by MbS to become king. Dietl also said MbS was the author of the Qatar crisis. “I take him to be a war monger over all else,” she said.

With Qatar refusing to comply with Saudi demands, which include shutting down Al Jazeera, severing ties with the Muslim Brotherhood and downgrading relations with Iran, MbS has a major crisis at hand. “Iran, which fights Saudi on several other fronts including Syria and Bahrain, will welcome any opportunity to drive a wedge among the Gulf states,” said Paul. According to Kechichian, under MbS, the Saudi foreign policy “will be far more muscular, especially on the Arabian Peninsula, as the monarch and his son, along with all of the establishment, are anxious to muzzle opposition to the GCC agenda. Alliance priorities will dominate all ties and few will be allowed to transgress as we are now witnessing with Qatar.” In an interview with local television channels in May, MbS indicated that he was not looking at a reconciliation with Iran. “We are not waiting until there becomes a battle in Saudi Arabia. We will work so that it becomes a battle for them in Iran and not in Saudi Arabia,” he said.

The biggest challenge for MbS, however, will be on the domestic front. Realising that the Saudi economy cannot go on relying exclusively on its petroleum reserves—oil prices dropped by 60 per cent in the last three years—MbS had proposed an ambitious plan called Vision 2030. It is aimed at diversifying the Saudi economy by bringing down the dependance on oil, attracting investments to make Saudi Arabia a trade and technology hub, developing a non-Hajj based tourism industry, replacing foreign workers with locals, and going easy on the strict moral code prescribed by the ultraconservative clergy.

To finance his ambitious strategy, MbS has proposed to sell 5 per cent of Saudi Aramco, the world’s largest oil company, which could have a market value as high as $2 trillion. The initial public offering (IPO) of Aramco could take place late next year and the proceeds would go into the Saudi Public Investment Fund, a sovereign wealth fund, which has recently invested $3.5 billion in Uber. In May, during a trip to Russia, he met President Vladimir Putin, and, more importantly, Igor Sechin, who runs Rosneft, the Russian oil monopoly. An understanding between the two could fundamentally alter the global oil trading mechanism. Saudi rulers have rarely played an active role in running the oil industry, leaving it to technocrats. “MbS’s hands-on role has not gone down well with many in the royal family and the technocracy,” said Paul.

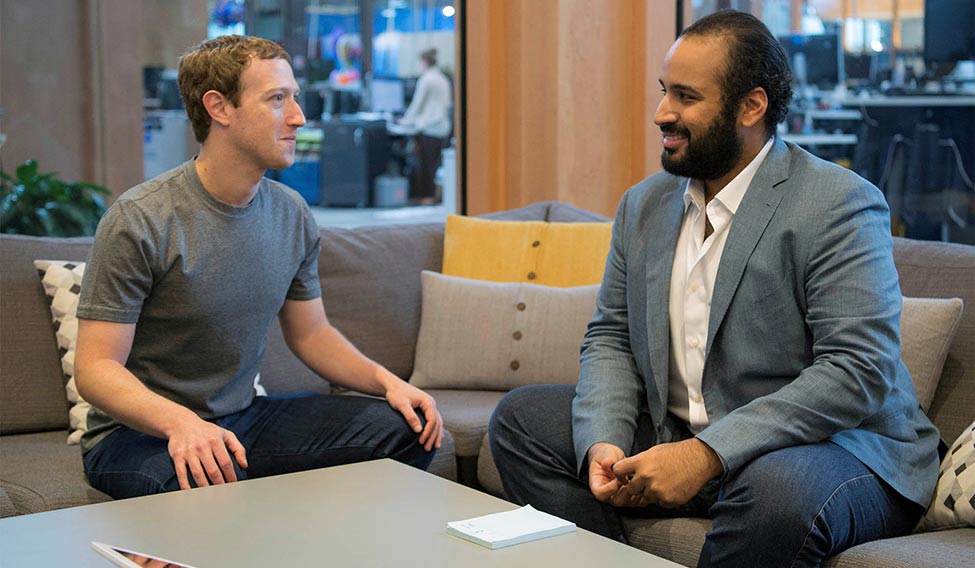

The young Saudis, who constitute nearly 70 per cent of the kingdom’s population, however, seem to be in support of MbS. They look forward to the youthful prince, who could rule them for decades. And, they already like what they see. More than his interactions with Obama and Trump, what attracted their attention was his visit to the Facebook headquarters at Menlo Park, California, where he was seen with Mark Zuckerberg, both wearing colour coordinated designer labels. And, back home, his move to set up an entertainment authority, which has organised music concerts, theatre productions and comedy shows and is even said to be thinking about opening cinemas, has been hugely popular. Equally popular is his decision to remove the power of arrest from the dreaded religious police and progressive views on allowing women to drive.

But the transition may not be easy. The cultural and societal liberalisation will come at a price. Saudi Arabia has historically ensured the loyalty of its subjects by offering them benefits from cradle to grave. Failed economic policies and dropping oil prices have forced MbS to impose austerity measures like rationalising salaries and perks of public sector employees and an increase in utility prices. It has caused major disaffection among people and forced some of the major private companies to explore bankruptcy options. Salman, in fact, had to reinstate most of the benefits of government employees, although as a celebratory gift to coincide with the elevation of MbS.

Any upheaval in the kingdom could be a cause for concern in India as Saudi is home to nearly 1.3 million Indian expatriates and supplies 17 per cent of its oil supplies. “Increasing Saudisation initiated by MbS would hurt the job prospects of Indians, especially the unskilled ones,” said Paul. Ties with a muscular Saudi will also have an impact on India’s strategic objectives. Pasha said there was a new multilateral alliance in the making between India, Saudi Arabia, Israel and the UAE, which is encouraged by the US. It was probably in response to this budding axis that Ayatollah Khamenei, the supreme leader of Iran, equated the situation in Jammu and Kashmir with that of Yemen as requiring the support of all Muslim nations, during his Eid-ul-Fitr address.

Kechichian said under MbS, Riyadh would follow established ties with South Asian countries. “It will continue friendly relations with all, especially India, for a variety of reasons, including critical commercial contacts as well as security relations.”