Eighty-five years after Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi undertook the historic Dandi march, demanding freedom from Britain, Bimal Gurung, head of the autonomous Gorkha Territorial Administration, has launched a march to revive the demand for a Gorkha state. Amidst allegations that he has forgotten the longstanding demand of the people of the hills, Gurung started the march from Kalimpong on October 2 and is expected to cover around 9,000km in 400 days, taking his demands to Delhi.

Critics say Gurung is desperate for an image makeover. "His movement is losing steam. So he wants to tell the people of Darjeeling that he did not forget the cause that made him a leader. But it will not work," says B.K. Pradhan, a lawyer from Darjeeling. Gurung is also worried about the Madan Tamang murder case in which he is the prime accused. Tamang, a moderate Gorkha leader, was hacked to death, allegedly by Gorkha Janmukti Morcha workers in 2010. Moreover, with the Narendra Modi government showing no signs of accepting the demand for Gorkhaland, Gurung probably thinks that something dramatic like a long march is his last option.

"I am yet to get the people of Darjeeling a state, although I had promised it. Only the Central government could give us that," says Gurung. “I have to tell the truth to my people so that they do not misunderstand me. I am going alone, as Tagore said. But the people of Darjeeling are with me."

Modi, who had described the aspiration of the Gorkhas as his own during the Lok Sabha election campaign last year, is yet to give them a patient hearing as prime minister. Gurung feels there is a broad consensus among the political parties of West Bengal against a separate state in the hills. So, he is reaching out to a wider audience with his march.

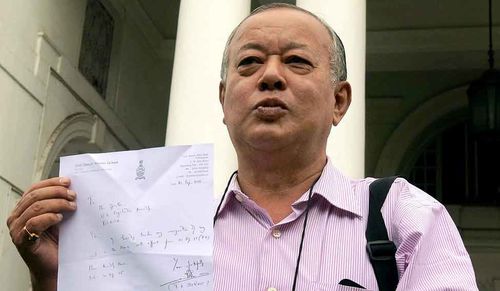

Trilok Dewan, MLA

Trilok Dewan, MLA

A school dropout, Gurung rose to fame after he snatched the baton of leadership of the Gorkhaland movement from his mentor, Subhash Ghisingh. "If I am unable to get you statehood, I will commit suicide," he vowed as he took over as president of the GJM. His supporters set ablaze government offices in the hills and shut them down. Non-Gorkha people were ordered to leave Darjeeling. Under pressure, the Central government initiated a tripartite dialogue with the state government and the GJM in 2008. As a temporary solution, the Gorkha Territorial Administration was formed as an autonomous body under the leadership of Gurung.

However, although it was decided that 59 subjects would be shifted to the GTA, only 36 have been handed over so far. Important departments like land reform and information and culture are still controlled by the Mamata Banerjee government.

Gurung calls Mamata his "biggest enemy". "I will not beg before her for statehood. I know she does not have the capacity to grant it. It is the prerogative of the Central government," says Gurung. He has asked the three MLAs of his party to resign from the West Bengal assembly and has written to the Central government that if a separate state is not possible, Darjeeling could be merged with Sikkim. "Darjeeling was never a part of Bengal. We will welcome any move to separate us from Bengal," says Gurung.

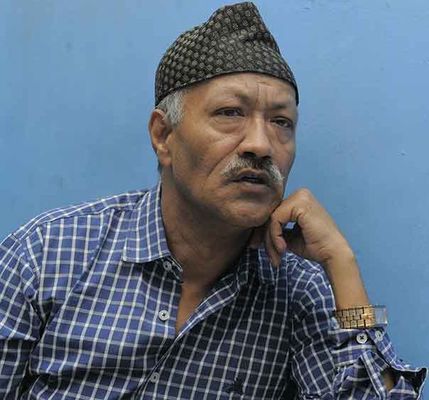

The flip-flop has not gone down well with many of his party leaders. Half a dozen of them have quit. Many of them say his march is just a big fuss which will get no result. "He was the tallest Gorkha leader in history. But today he is a joker," says Gurung’s one-time associate Harka Bahadur Chettri, who is the MLA from Kalimpong.

"For the last ten years I was with him. But I failed to educate him. He is an uneducated and directionless person. How could a movement of this magnitude, to earn statehood for these beautiful hills, be led by such an irresponsible person?" asks Chettri. He says the movement needs an educated person to take it forward. "Gurung has been running the show using money and muscle power, which is going to end soon," says Chettri, who has refused to resign from the assembly.

Harka Bahadur Chettri, MLA, and Gurung’s one-time close associate

Harka Bahadur Chettri, MLA, and Gurung’s one-time close associate

Chettri is not alone. Trilok Dewan, the MLA from Kurseong, could not control his temper after Gurung's call to quit. Dewan, who retired as chief secretary of Andhra Pradesh, told him that he would quit the party membership, too. "I was stunned when he asked me to quit," says Dewan, who was Gurung's chief adviser. "He and some of his close associates took the decision and thrust it upon all of us. It is a complete dictatorship."

As a person who oversaw the administration of Andhra Pradesh in the early years of the last decade, Dewan says it is ridiculous to compare the Telangana movement to the Gorkhaland movement. "Popular movements alone did not bring statehood to Telangana, Jharkhand or Chhattisgarh. Political leadership in those areas did a lot of lobbying. I had seen how politicians from Telangana lobbied for a new state," says Dewan. “But in the case of Darjeeling, the leadership is not taken seriously by the Central government. The creation of new states in those cases was a matter of compulsion for Delhi. In our case, there is no such political compulsion."

Chettri, whose name also figures in the Tamang murder chargesheet, is so disillusioned with the Gorkhaland movement that he has asked Mamata to create a new district of Kalimpong, separating it from Darjeeling. He says Mamata has indicated her willingness to consider the demand. "But she has asked me to demonstrate support for such a demand. I am working on that. I have forgotten the Gorkhaland issue," says Chettri.

Despite the opposition that is building up against him, Gurung is upbeat. "Have faith in me," he tells people whom he meets during his march. "I will not let you down. Gorkhaland would take time."

Gurung says the padyatra is a gentle reminder to the Centre to hasten the promises it made. Some of his close associates seem convinced. "The previous agitation only hurt the people of Darjeeling. Our economy suffered as tourists stayed away. Our youth became jobless," says Roshan Giri, the GJM’s second-in-command. "This time, Gurung would show the development card and simultaneously demand Gorkhaland. He has adopted the path of Gandhi only after giving it careful consideration."

Stagnant state

* The district of Darjeeling, in north Bengal, covers 3,150 sq km and has a population of 18 lakh, most of them Gorkhas.

* Historically, Darjeeling was not a part of Bengal. It was leased by the British from the kingdom of Sikkim in 1835.

* Demand for a separate province for Gorkhas first surfaced in 1907. The first popular movement for a Gorkha state was launched in 1986-88 by Subhash Ghisingh, who founded the Gorkha National Liberation Front (GNLF). Nearly 2,000 people lost their lives in the uprisings. It led to the formation of the semi-autonomous governing body called the Darjeeling Gorkha Hill Council (DGHC) in 1988.

* Bimal Gurung, a member of the DGHC, broke away from the GNLF in 2007 and set up the Gorkha Janmukti Morcha.

The GJM allied with the Trinamool Congress in the 2011 assembly elections. After its victory, the Trinamool government set up the Gorkha Territorial Administration to govern the three hill subdivisions, Darjeeling, Kurseong and Kalimpong. Gurung resigned from the GTA to press for statehood in July, 2013.

* With no palpable progress on the statehood front, and to tackle the rising tide of unpopularity, Gurung has launched a padyatra (in pic). The march, which started from Kalimpong on October 2, will cover around 9,000km in 400 days, taking the demand of statehood to Delhi.