It drizzled that morning, wetting the kerbsides and getting the umbrellas out. A host of men in uniform—traffic cops with their fluorescent bands, secret service men and women in black, military guys in their camouflage khakis and plainclothesmen in crisp suits—patrolled the streets and regulated access to the various five-star hotels and the massive Walter E. Washington convention centre. Periodically, the air was rent with shrill sirens as yet another motorcade zipped past. All the while, overhead, helicopters hovered. With representatives, mostly heads, of more than 50 countries and four international organisations (Interpol, United Nations, International Atomic Energy Agency and European Union) gathered to discuss how to keep nuclear explosives out of reach of terrorists, the setting was almost out of a Hollywood directed apocalyptic thriller.

This was, however, the real thing. Heads of state huddling together at the Nuclear Security Summit (NSS) 2016 to secure fissile material from reaching wrong hands. A challenging task, no doubt, given inter-country rivalries and threats.

Take, for instance, the absence of Russia from the summit. United States President Barack Obama, later talking to the media, admitted that the bulk of fissile material in the world was in the hands of the US and Russia and without the two working together, nuclear security was not possible.

Another axis of challenge, according to Obama, was India-Pakistan; he expressed concern about the direction their military escalations could take. Here, too, the absence of Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, who cancelled his trip following the suicide attack on Easter Sunday, set tongues wagging. Other countries beset with threats and violence, including Turkey, had made an appearance. Was Sharif trying to avoid difficult questions on Pakistan's response to terror, said the whispers. Obama called up Sharif to express support, but it was clear that Sharif’s absence wasn’t appreciated. And, by seating Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Chinese President Xi Jinping on either side of him at the inaugural dinner, Obama made a strong statement.

And even as the US got into the longest trilateral huddle with South Korea and Japan, Pyongyang fired a short-range missile into the sea, thus underscoring the instability in the Korean peninsula.

Meanwhile, outside the venue, other manners of protests put the spotlight on local tension spots, which could flare up anytime. Tibetan protesters had their flags up against Jinping, banners sponsored by modifail.com urged Modi to stop attacks on minorities back home and at an event at Brookings Institution, protestors denouncing Turkish President Tayyip Erdogan for his anti-Kurd stance got into ugly spats with security men.

Overshadowing all these inter-country frictions, however, was the trans-border threat of terrorists, especially Islamic State. The attacks in Brussels, just days ahead of the NSS and the India-European Union summit, re-emphasised the need to secure weapons-grade nuclear material from the bad boys. The talk among delegates as well as among experts at the parallel NGO summit was about the video footage of a Belgian nuclear scientist who was being spied on, purportedly so that his movements could be studied. Was there a plan to kidnap him and lay hands on fissile material?

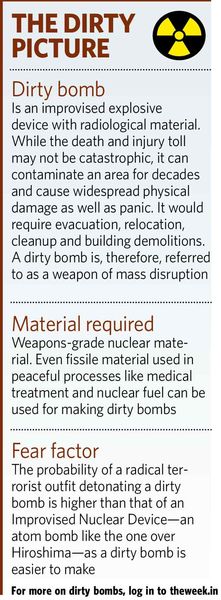

Of the four sessions at the summit, the final was a closed-door one where world leaders actually did a scenario-based discussion on what reactions and responses to set in place in the event of terrorists securing a dirty bomb. The dirty bomb—an improvised explosive device with fissile material—was the talking point of the summit and discussions, and studies presented at various fora went on to show just how easy it can be to make one.

“Just imagine if they had used a dirty bomb in Brussels. The airport would have been contaminated, it would take decades to clear the mess. Imagine the social, psychological, physical and environmental impact of an event like that,” said Paul Walker, founding member of Fissile Material Working group, and a strong advocate for abolishing chemical weapons.

“Al Qaeda has often expressed intention of acquiring a nuclear weapon. IS is the most current threat. Just because they have not acquired one yet is no reason to lower our guard,’’ said Joan Rohfling of Nuclear Threat Initiative.

The NTI has listed at least three instances where security was compromised. Three peace activists managed to break into a nuclear security complex in Tennessee in 2012, which houses a large amount of highly enriched uranium. It took half an hour before a security guard noticed them. In 2013, US nuclear missile launch officers were caught sleeping with the blast door open to their missile launch capsule. The same year, 50 UK military personnel were investigated for sleeping at their job at the Atomic Weapons Establishment, Berkshire.

Modi, in his speech, alluded to the “insider threat”. “State actors working with nuclear traffickers and terrorists present the greatest risk,” he said. Though joint secretary (disarmament) Amandeep Gill refused to elaborate, the reference to the father of Pakistan’s nuclear bomb, Abdul Qadeer Khan, and his alleged nuclear black market was clear. The Pakistani delegation said its nuclear programme was modest compared with India’s ambitious one and much more secure.

Terrorists don’t necessarily need to access a military establishment though. The same isotopes that make lifesaving blood transfusions and cancer treatment possible can be ingredients for making a radiological dirty bomb. NTI says many of the sites in 100 countries where these materials are located are vulnerable. India, China and Russia have the largest stockpile of radiological material and none of them have signed up to secure the material yet, says NTI.

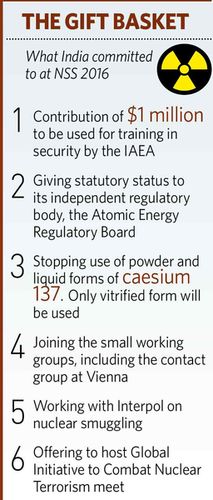

As the final of the four Obama-initiated summits wound up, with considerable achievements, the road ahead continues to be fraught with difficulties. On the bright side, several countries, with Argentina being the latest, have come out clean, having completely disposed of or neutralised their stock of radiological material. According to Obama, US and Russian nuclear arsenals are the lowest in six decades. The US plans to stop using weapons-grade nuclear material in its naval submarines, while France has stepped up action to locate French-origin radiological material in countries with poor capabilities of securing them. France plans to repatriate this “orphan material” from a dozen sources in West Asia and Africa between 2016 and 2018. India, meanwhile, announced it had stopped using caesium 137 (a medical treatment radiological material) in the more vulnerable liquid and powder forms and will only use the vitrified form.

Such contributions to the gift basket—voluntary commitments and contributions—poured in, but the lacunae were made all the more glaring. “We still need that comprehensive global commitment that all nuclear weapons and all materials that can be used to make an N-bomb must be secured,” said Mathew Bunn of the Fissile Material Working Group.

While the Convention on the Physical Protection of Nuclear Material is likely to come into force soon, thanks to NSS pressure and effort, NTI says there is still no standardisation, so efforts are piecemeal. “Again, there is little in way of getting countries to tell what they are doing, except what they voluntarily disclose,’’ says Samantha Pitts Kiefer of NTI.

The momentum of nuclear security is now expected to be taken forward by Sherpa (team leaders designated by individual countries) groups at various fora like IAEA and Interpol. “We have agreed to build new nuclear security contact groups,” said Obama. It is a legacy he is keen to see transform into something bigger. It was for this initiative in part that Obama won the Nobel Peace Prize.

But every effort finds huge walls when confronted with the reality that the powerful nations may advocate security on the one hand, but are refining their nuclear arsenals on the other. Obama admitted that though the arsenal was diminished, it was important to keep what they had up-to-date and in working condition. He also announced there were no plans to further reduce the arsenal.

“This is where it all halts,” said Des Browne, co-chair of NTI’s military materials security study group and former US secretary of state for defence. “Only 17 per cent of radiological material is in civilian facilities worldwide, so even after securing it all, you still have to tackle the remaining 83 per cent. Most of this is in the US and Russian arsenals. So you cannot talk of nuclear security without disarmament. And disarmament means the US and Russia.’’