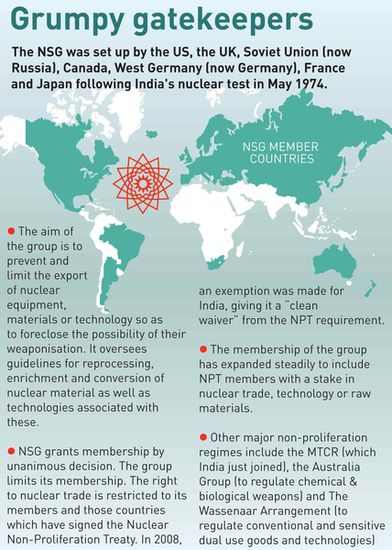

On the morning of June 20, at a quiet event in South Block, foreign secretary S. Jaishankar signed a document in the presence of the ambassadors of France, the Netherlands and Luxembourg. India thus became the 35th and newest member of the Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR), one of the four coveted nuclear control clubs.

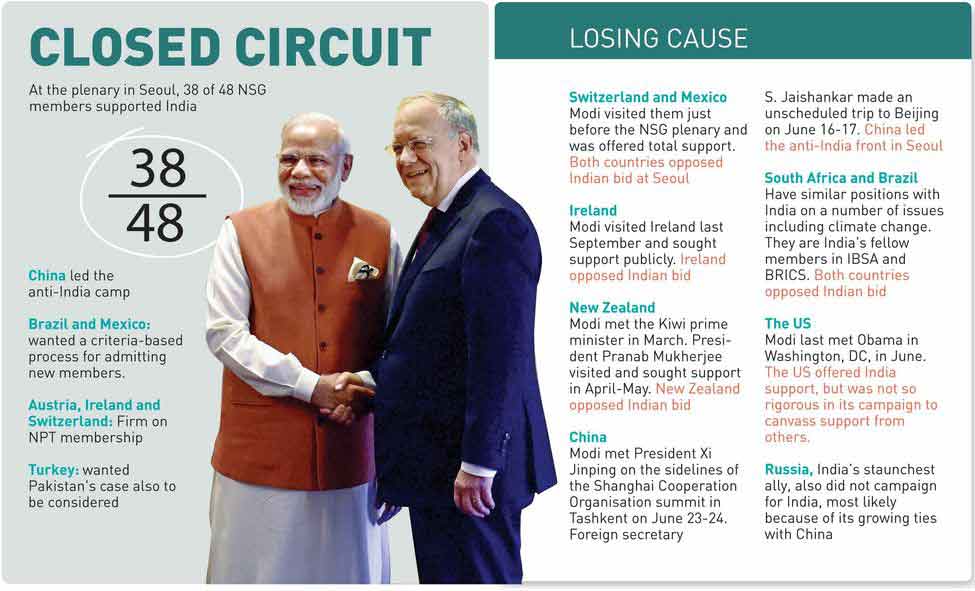

The event, however, was not much of a salve to a nation that had just two days earlier, been denied entry into the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG). It was less disappointment, more embarrassment. Mandarins of the ministry of external affairs squarely put the blame on “one country’’, without naming China, for being left out. It did not take long, however, for the news to emerge that apart from China, at least eight other countries—Brazil, South Africa, Ireland, Austria, New Zealand, Turkey, Mexico and Switzerland—also had raised objections to India’s application. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s personalised brand of soft diplomacy had given jaadu ki jhappis (magical hugs) to several of these nations, and so their NSG objections have turned out to be rather insulting.

Modi had, only days earlier, returned from a multi-nation tour, which included Switzerland and Mexico. During the visit, Swiss President Johann Schneider-Ammann had said, “We have promised India support in its efforts to become a member of the NSG.” In September 2015, Modi had visited Ireland and announced that he had sought Irish support for India’s NSG bid. Brazil and South Africa are India’s partners in BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) and IBSA (India, Brazil and South Africa) and Modi engaged with South Africa further at the India-Africa summit in Delhi last year. President Pranab Mukherjee, who visited New Zealand in April-May, had requested its support. Modi, who met New Zealand Prime Minister John Key at the Nuclear Security Summit in Washington, DC, in March, had worked his charm on him. Had Delhi thus thought it had the world in its pocket? That even if the NSG did not come India’s way, there would be a substantial gain in getting China to play the lone spoiler, making it appear churlish and petty? If that was so, it was a serious misunderstanding of signals, experts point out.

“I think the MEA has not been able to communicate well. What did these countries actually mean when they claimed to be extending support?’’ says Bharat Karnad, professor of national security studies at the Centre for Policy Research, Delhi. “Then again, we made certain assumptions, like since the US was on our side, Ireland, too, would be. And Turkey was never in the picture, despite Turkey’s stand that it would always hyphenate India and Pakistan.’’

Grahame Morton, high commissioner of New Zealand to India, says his country’s stance on NSG membership has always been well known, so there was no question of giving wrong signals. He says his country is not opposed to India’s entry, but it wants the criterion for admitting countries which have not signed the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) spelt out first. So why hadn’t the Kiwis communicated this stance to India? “India applied only in May,’’ says Morton. “And it is the first non-NPT country to apply.’’

Even China, which had repeatedly stated that it would not allow India entry, was wooed at every given opportunity. Modi made a last-ditch effort with President Xi Jinping in Tashkent during the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) meet just days ahead of the NSG plenary session in Seoul. Before this, Mukherjee and Jaishankar had tried softening the Chinese on their home ground. “India miscalculated the Chinese degree of hostility. Modi thought that by giving China market access, they would be more amenable. Perhaps this is why he kept trying till Tashkent,’’ says Ashok Malik of Observer Research Foundation, Delhi. Of course, the iron was hot. With President Obama in the White House, the support was assured. His successor might not be on the same page next year. If India waited for one more year, Modi’s term would be nearing its end. “We had to strike now. But we should have prepared a little more,’’ he says.

The NSG was a mishap on several counts. “What was the need to make it such a high profile campaign with Modi openly canvassing? It should have been left to diplomats, and only when we were absolutely certain, should we have projected Modi,’’ says Karnad. This was iffy from the beginning, given China’s stance.

Again, as this was India’s first bid, and given its position on the NPT, there were bound to be speed breakers. “We didn’t get MTCR at the first shot either,’’ says Rajiv Nayan, researcher on nuclear issues at the Institute of Defence Studies and Analyses, Delhi. India had made a bid for MTCR last year, but it was scuttled by Italy, apparently miffed at India’s handling of a case involving two Italian marines. That particular thorn was removed after the marines were sent home.

But why was India so desperate for these memberships? The 2008 waiver given to India by the NSG allows it access to nuclear fuel, which it requires. The waiver does not give access to enriching and processing technologies, both of which it does not really need. India, incidentally, has mastered the three fuel cycles, with uranium, plutonium and thorium. External Affairs Minister Sushma Swaraj had earlier noted that the difference was that of being outside the room and being inside. If inside, one is privy and is participatory to discussions and decisions; if outside, one’s position is passive.

“It is more of a branding exercise than anything else,’’ note observers. MEA always raises the concern that the waiver is an iffy thing, which could be revoked at whim. “That’s not entirely correct,’’ says Karnad. “Also, revoking a waiver means that India is free from any shackles, and that’s not a situation the world would like.’’

MTCR places voluntary restrictions on members with regard to exporting missiles and missile-related technology. Now, as member, India has easier access to technology for its space programme, for instance. But does India, which has etched a name for itself in developing thrifty technology, now need to import? MTCR membership will also help India in exporting its BrahMos missiles. “These memberships do give some advantages, undoubtedly, but we need to see what price we are paying for them,’’ says Nayan. China, incidentally, is not inside MTCR yet, despite applying several times.

There has been a minor victory on the NSG front, too. The group is likely to meet again this year (instead of next year) to discuss the entry of non-NPT countries, following a suggestion by Mexico. Experts, however, caution that India needs to assess whether the price is worth the prize. India had to step down from its stand at the climate summit in Paris that developed nations should take “historical responsibility’’ for the environmental damage [thereby contributing more to mitigation]. This position was causing a stand-off at the summit. India took a step back, perhaps because Modi had become best friends with Obama (who saw the summit as a legacy) and French President Francois Hollande (who was hosting the summit). In return, India got backing for its solar alliance, and perhaps tacit support for entry into hallowed clubs.

Club memberships, as we know, come after long waits and heavy price. But once in, we either rarely use the facilities or realise we didn’t quite need to be in a club to get them.