Scientists at the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) are running the final checks on an ambitious project, with which India’s space programme will expand from one of national development to that of regional development. The South Asian Satellite is getting ready for a launch, sometime at the end of March.

The satellite was what Prime Minister Narendra Modi magnanimously promised to member nations of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation in 2015. India is the only spacefaring nation in the bloc. Modi’s promise has finally shaped up as a satellite of the 2K class (which has a weight of around 2,000 kilos) that could become the provider for a host of communication applications within individual countries as well as between them.

The vehicle aboard which this ambition will soar itself is an important one, the Geosynchronous Space Launch Vehicle Mark II, a heavy duty rocket. Every launch of a GSLV Mark II is crucial, given that a rocket of this class will be deployed for Chandrayaan-2. Unlike the success rate of ISRO’s old reliable Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle, the GSLV’s track record is not that stellar. However, in its Mark II version, the vehicle, which has a cryogenic engine developed along with Russia, has been declared a motorable car.

But let’s get back to the satellite first. What exactly is it going to do? M. Annadurai, director of ISRO’s satellite centre at Bengaluru, where the satellite is being given the finishing touches, says that it is a “communication satellite”. This means that the satellite could be used in areas like tele-education, tele-medicine, e-governance, disaster management and even direct-to-home television. “Our role at ISRO is to provide the network, and to maintain the health of the system. It will be up to individual countries to develop programmes which can make use of this network.” Indeed, the possibilities are as endless as people’s imagination—a hotline between two or more countries, direct television transmission, for instance.

So far, agreements on orbital frequency coordination have already been signed with Sri Lanka, Nepal, Bhutan and the Maldives. Pakistan, in 2016, conveyed that it would not participate in the project, after which the SAARC Satellite was renamed the South Asian Satellite. India is still working on agreements with Bangladesh and Afghanistan. But what if these agreements are not inked by the time of the launch? ISRO scientists say that shouldn’t be an issue. They can, with minor technical adjustments, sync the satellite to future requirements. In fact, even if Pakistan has a change of heart, it can be accommodated at a later date. India is bearing the entire cost of designing, launching and maintenance of the satellite. The cost of just launching a GSLV II is around Rs 230 crore. The satellite should have a functional life of around 12 years.

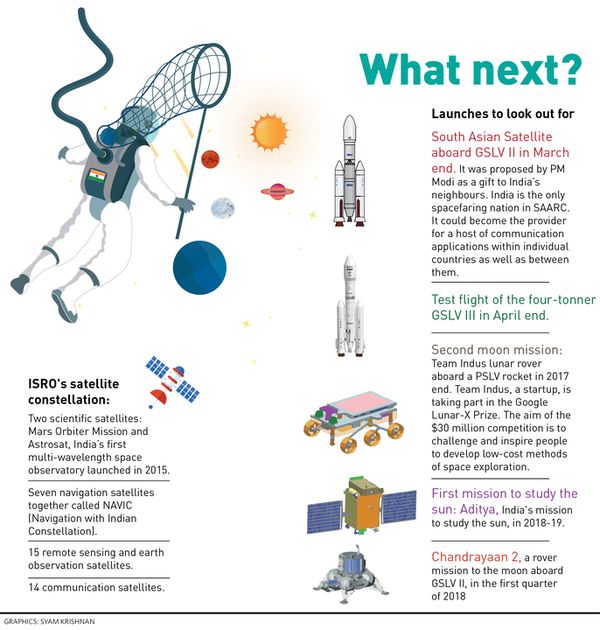

Low cost launches of smaller satellites have become ISRO’s USP. Most of them have been aboard PSLVs (One launch costs Rs 100 crore and India has begun offsetting the expenses by taking in passengers from other countries.) PSLV, however, cannot take satellites heavier than 1,800 kilos, which is why ISRO needs reliable heavier vehicles. GSLV II will be able to take satellites of up to 2,500 kilos. And the GSLV III, a test flight of which is scheduled in April, will have a four-tonne capacity, making it the heaviest launch vehicle from ISRO. These rockets are required as India upscales its space ambitions.

India is already thinking of another mission to Mars and a maiden one to Venus. A human space flight is also somewhere in the bucket list. With so many launches, ISRO itself has a minor constellation of its own satellites operating in various space orbits around the earth. And what exactly do they do? Fifteen of them are remote sensing satellites, which make earth observations. Fourteen are communication satellites, which are also used by private operators for television networks. Seven satellites form NAVIC, providing an indigenous navigation network. This is mainly for the Navy, so that it doesn’t have to rely on foreign navigation systems like GPS or Galileo, whose services can be withdrawn in times of hostilities. Only two satellites are scientific ones, the Mars Orbiter Mission, orbiting the red planet and, Astrosat, a space observatory.

India’s space direction has largely been of national development, says Annadurai. Some agencies like the Met department and agriculture, forestry and fishing ministries have been using satellite data for long. The big boost has come just a couple of years ago, with Modi’s push for a digital India. “Four years ago, 18 government ministries and departments were using the ISRO services, today, there are 80. Much of this happened after ISRO was told to have a meeting with various government agencies, explaining to them how satellite information could be used,” Annadurai elaborates.

Among the new uses is monitoring unmanned level crossings by the Indian Railways. The postal department has launched another interesting project of geo-tagging places in India. “As postmen go to various parts to deliver mail, they also geo-tag the area, thus creating an extensive database,” said the ISRO scientist. The Archaeological Survey of India is using satellite information to map boundaries of heritage sites.