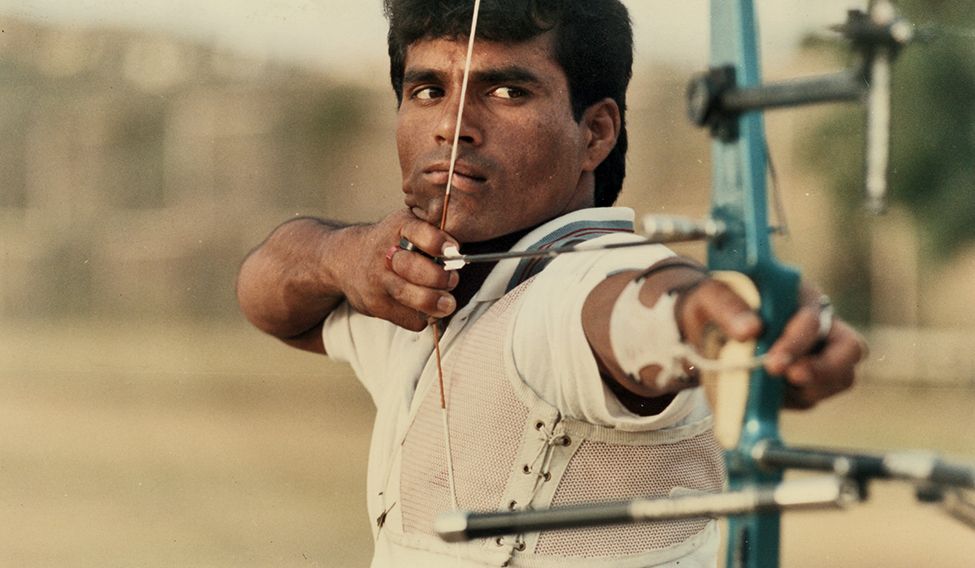

What is common between Limba Ram, Dilip Tirkey and Baichung Bhutia? Granted, they are all sporting icons who had humble beginnings.

From being a teenager earning Rs8 a day at a farm in Udaipur in Rajasthan, Ram became a champion archer who led India to victory in the international arena. Tirkey, who belongs to the Oraon tribe in Sundergarh district in Odisha, led the national hockey team. As member of the Rajya Sabha, he now handles myriad issues related to the development of tribals. Bhutia's spectacular rise from Tinkitam in Sikkim to become the torchbearer of Indian football has been an inspiration for budding footballers.

What binds them together is the fact that they were all products of flagship schemes of the Sports Authority of India. Limba, along with teammate and fellow Rajasthani Shyam Lal, were the poster boys of the Special Area Games scheme, one of the most talked about SAI projects. Bhutia and Tirkey were one of the many success stories of SAI's National Sports Talent Contest scheme.

An autonomous arm of the Union ministry of youth affairs and sports, SAI was formed after the 1982 Asian Games in New Delhi. From being an organisation entrusted with the task of maintaining five stadiums constructed for the Asian Games, SAI has grown to become a sports behemoth that performs multiple tasks such as spotting, nurturing and training talent, providing equipment and facilities to athletes and coaches, funding the training of elite athletes, constituting national teams, developing sports infrastructure, and maintaining and upgrading stadiums and sports complexes funded by the Union government.

Of late, SAI has been in the news for all the wrong reasons. On May 6, four female athletes at the SAI watersports centre at Alappuzha in Kerala tried to kill themselves. One of them died, while others were hospitalised in critical condition. The athletes were allegedly harassed by the teaching staff and senior athletes at the centre. Injeti Srinivas, who took charge as director-general of SAI in March, termed it the “most shocking and tragic incident in SAI history”.

Hockey player Dilip Tirkey | PTI

Hockey player Dilip Tirkey | PTI

According to him, the incident has become the trigger for upgrading systems at SAI. Many of SAI's flagship schemes are in urgent need of a revamp or, if need be, closure. Sources told THE WEEK that Srinivas had expressed concern over the state of SAI soon after took charge from Ajit Sharan, secretary (sports) at the ministry, who was holding additional charge of SAI. Apparently, Srinivas said “some of SAI's flagship schemes were not meeting their purpose”. At a meeting, one official even said that some schemes were “in the ICU”.

In a report submitted to a parliamentary committee in 2012-13, the sports ministry said the performance of SAI was satisfactory, considering its financial constraints and the number of medals it had helped India win in international competitions. The committee, however, did not accept that view, as the ministry had pointed out that the government had allocated Rs750 crore the previous year just to train athletes. Even as the report outlined various SAI schemes and their implementation, it did not analyse their effectiveness, said the committee.

In the past 28 years, athletes trained by SAI have won as many as 1,449 medals at the international level. It translates to more than 51 medals a year. The parliamentary committee, however, said it was not too impressed by the statistic.

Many people share Srinivas's concern over SAI's health. Olympian Ashwini Nachappa, who is part of the governing body of SAI, recently wrote to leading sportspersons about the urgent need to revamp SAI and its schemes. “For the first time, SAI has many sportspersons on its governing body,” she told THE WEEK. “We are demanding that the very mandate of SAI be re-looked.”

Nachappa said that sports bodies abroad, even those that were funded by governments, were run by qualified people. SAI needs to replicate the practice. “There is no defined mandate for SAI. It just fulfils the requirements of national sports federations, be it for coaching, training or hosting events,” she said.

Such is the state of affairs that SAI's governing body has met only twice since 2012. The third meeting is expected to be held on May 26. “We [the governing body] should be meeting once in three months,” said Nachappa.

SAI has six flagship sports promotion projects: the National Sports Talent Contest scheme, the Army Boys Sports Company scheme, the Centres for Excellence, the SAI training centres and their extension centres, and the Special Area Games scheme. On paper, the schemes are pyramidically structured, with the talent contest scheme reaching out to the grassroots and scouting for promising athletes aged between eight and 14 years. Launched in 1985, the scheme gives incentives to amateurs and schools that have a good record in sports. Officials at SAI staunchly defend the scheme, saying it has helped discover top-quality talent.

According to SAI, there are ten regular schools, ten schools promoting indigenous games and 32 akharas adopted under the scheme, which trains 805 boys and 255 girls. Schools receive an annual grant for equipment, while trainees get sports kits, medical insurance cover and a stipend of Rs300 per month. Grapplers in akharas get Rs1,000 as monthly stipend.

The parliamentary committee had rapped the ministry and SAI for low stipends and medical insurance cover, saying they were grossly inadequate. Subsequent governments, however, have done little to help SAI increase the stipends and insurance cover.

The pathbreaking Special Area Games scheme, launched in 1987 by then Union sports minister Margaret Alva, scouts for talent in remote areas of the country. It aims at identifying and training candidates belonging to communities that are perceived to have genetical, physiological or geographical advantage in certain sports disciplines. Theoretically, when it comes to endurance events like long-distance running, tribals living in high altitudes have an advantage over those living in coastal areas.

The brief of SAG teams is to scout for talent in specific areas, bring selected candidates over to a laboratory, run basic parameters tests and enrol the best in the scheme. The teams usually focus on communities such as the Siddis, who are descendants of Bantu people of southeast Africa, and tribes in the northeast and Andaman and Nicobar Islands.

As many as 1,676 athletes train at 19 SAI centres operating under the scheme. The watersports centre in Alappuzha is part of it. Being a coastal district, Alappuzha has traditionally been a centre of water sports. The SAI centre there gives training to athletes in events like canoeing and kayaking.

The scheme was massively popular at the time of its launch. The Alappuzha centre, for instance, received as many as 800 applications when it opened in 1987. In the end, 180 applicants were called for interview and 17 were selected. For the first three years of its inception, the scheme was a success. But it has been a non-performer in recent times. In fact, Nachappa says it is “as good as closed down”.

Even B.V.P. Rao, who was first in-charge of the scheme, admits that it has run out of steam. “Even though it has been continuing, the thrust is gone,” he said. “For a long time, officials have not taken much interest. It produced Olympians in the first three years. But how many have come after that?”

The Army Boys School Company scheme is a collaborative venture of SAI and the Army. It gives training to Sainik School students aged between eight to 16 years. When trainees turn seventeen and a half years, they are offered placement in the Army. Since the Army has a long tradition of nurturing sports talent and preparing them for the highest level of competition, SAI officials say the scheme continues to yield results.

“It is a very good partnership, done very well,” said Srinivas. “It is the best in the bouquet of [SAI] schemes. As many as 99 per cent of kids get into the Army by virtue of their performance in sports. We are trying to increase the number [of training centres under the scheme] by about five to ten a year. We have gone to the Air Force, the Navy and the paramilitary. We are trying to expand the scheme in a very big way.”

Perhaps, the need for reforms is most evident in the case of SAI training centres and special centres. Over the years, they have played a role in nurturing and providing top-tier talent for the country. And, they have been a good example of the Central and state governments working in tandem. State governments provide all facilities and infrastructure, while SAI gives lodging, training and equipment to athletes.

Currently, there are 75 SAI centres training 5,394 athletes. Of late, the output of the centres has been below par. Nachappa believes that their number needs to be reconsidered. “We need to look at how well they are equipped to cater to today's athletes,” she said. “I strongly feel we need to close down a few. Manage a few schemes, but really effective schemes.”

In some states, there are multiple SAI centres. But, in terms of coaching and facilities, not all are of the same level. For instance, SAI has five centres in Haryana, but the facilities in Bhiwani and Rohtak are starkly different. The Rohtak centre, home to the proposed National Boxing Academy, boasts modern infrastructure and generous support from the state government. But the conditions in Bhiwani, as per SAI's own report, are “deplorable”. Launched in 1987, the centre has trained several Olympic-level boxers. But issues like audit objections over SAI upgrading state-owned infrastructure have been stumbling blocks.

Apparently, Srinivas is planning to decentralise the SAI training centres. “STCs will be revamped in such a way that each centre will have its own micro plan,” he said. “We have 75 STCs, so we have to have 75 plans. Then we will ask public sector units to adopt them as part of their corporate social responsibility initiatives. We will also approach corporates, but since we are a government agency, we will go to PSUs first.”

At the top of the SAI training pyramid are the Centres of Excellence, a project launched in 1997 to provide advanced training to the cream of Indian sports—those who have excelled in senior- and national-level competitions—through SAI regional centres. The Centres of Excellence operate as regular coaching camps that are open 330 days a year. As they provide the best training facilities for athletes, the centres regularly host national camps organised by various sports federations.

SAI officials say the project needs to be upgraded. “The RCs [regional centres] need to be restructured and revamped,” said an official. “They are not there for nothing. They do an important job.”

Several of SAI's regional and training centres suffer from shortage of staff and trainees. At times, say officials, there is not enough strength to conduct team games. For instance, some centres do not have a team B to hold hockey matches, and grapplers and boxers often do not get sparring partners. Also, shortage of coaching staff continues to be an issue. SAI recently announced that it would be hiring 119 coaches on contract. But it is too small a number to cater to all of SAI's coaching facilities and schemes.

There has always been a lack of political will and administrative gumption to revamp SAI. At a time when sports is embracing cutting-edge technology and training methods, India's premier training institution has fallen behind the times. SAI centres in urban areas have stopped attracting promising athletes. In fact, the situation is such that, for want of a few stitches in time, SAI is now in need of an urgent surgery.

Interview/ Injeti Srinivas, director-general, SAI

Money is not a constraint for SAI

By Neeru Bhatia

Damage control: Srinivas speaking to relatives of Aparna Ramabhadran, who committed suicide at the SAI centre in Alappuzha.

Damage control: Srinivas speaking to relatives of Aparna Ramabhadran, who committed suicide at the SAI centre in Alappuzha.

Injeti Srinivas, today, sits on the other side of the fence. Five years ago, he was a major driving force in the Ministry of Youth Affairs and Sports. As Joint Secretary, he cracked the whip on errant National Sports Federations and had warned of the downside of the Indian Premier League.

After a cooling period that included postings in Afghanistan and his stint as chairman of the National Pharmaceutical Pricing Authority, he has been brought back to the sports ministry to sort out SAI. Handpicked by the Centre, Srinivas is already in action mode. SAI is undergoing a review and recommendations are being acted upon. He is the first Director General of SAI who is not bemoaning resource crunch. He believes there is no budgetary constraints.

In a chat with THE WEEK, Srinivas reveals which SAI flagship schemes are being wound up and which ones will assume importance. Excerpts:

What are your views on the existing schemes?

It is time to revisit some of these schemes. These are very well thought-out schemes; but what was relevant and of high priority in mid 80s and through the 90s may not be the same today. We have had several review committees which have evaluated these schemes and lot of suggestions have been made. Right now, we are in process of restructuring our promotional schemes.

If you look at our evaluation, maybe it is time to withdraw the National Sports Talent Contest (NSTC) scheme which was linked to schools. We feel this may not be neccessary because state governments have a reasonably extensive coverage at school level.

SAI has to pick talent established more at state and national levels. If we withdraw from NSTC, some of our resources could be used to strengthen our core schemes.

What about the numerous STCs and extension centres? Are they all doing the job they have been created for?

STC is our core programme. Let's not undermine that. There is absolutely no second thought on that. STC is according to centre-state partnership model. We expect good infrastructure to be made available by state governments. Coaches, equipment, sports kit, competition and exposure—all that will be taken care of by SAI.

Some of the STCs are very good, while others are in deplorable conditions.

It's very important that infrastructure is of acceptable standards. We have to conduct proper audit of infrastructure and minimum benchmarking has to be done. Bare minimum needs to be same in all STCs . Some state governments are very generous and improve on these, which is most welcome.

Interaction between SAI and states and joint accountability is very criticial.

Are standards of coaching resources and trainees satisfactory?

We are looking at a friendly but comprehensive evaluation system for trainees and coaches. This is at a very advanced stage. This may take about three months.

Technology interventions take some time.

The same non-compromising yardstick will apply to deployment of human resources also.

Will you shut down some STCs , extension centres or merge one with other if a centre isn't working as per standards?

I am not in favour of shutting down just like that, it has huge negative impact. No response in catchment area, lack of talent and sporting excellence could be the only reasons for shutdown. More often than not, there is lack of coaches, infrastructure, competition exposure and sports science support—these can't be reasons for shutting down centres. The centre has to continue and improve.

STCs will be revamped, categorised and supported according to where they stand in the matrix. Each STC will have a micro plan.

We have 75 STCs, so we have to have complete 75 plans. Then market these well to central PSUs so that they can be adopted as part of CSR initiatives. We will also go to corporates, but since we are under the government, we will go to PSUs first.

Threre are theree cartegories of STCs. Category A—outstanding in infra structure and performance, B—outstanding in either one and C—mediocrity in both. Category A will be looked at very closely for making them specialised STCs working at the national level. The selection process will look at national-level competitions from all states and these will then function like national academies.

SAG is as old as SAI and has passed its expiry date.

SAG is a very specialised concept and somewhere down the road we have lost the approach to it. It needs to be revisited again. SAG will go where people don't get exposure to modern sport. We will go there, set our training centres and expose them to competition.

The whole process of testing for SAG talent was at a very theoretical level. It is historical knowledge and already established.

Isn't SAI hampered by budgetary constraints?

I have never found budgetary constraint with any organisation including SAI. If all other non-core areas are eating into my budget, I have the competence to distribute them, right? If other things are required, then money will come. Constraint is in our capacity, willingness, ability to sustain and manage issues with challenges.

Will you be hiring more coaches, as of now its 119?

Can I hire 1,000 coaches in one go? 1,000 will retire in one day. Phasing happens.

Regional Centres and Centres for Excellence—are you happy with status quo?

Some tweaking will have to be done with RCs. Thats natural, some are overburdened, some underutilised. Some geographical restructuring has to be done. Some other states also have aspirations—they want their own own RCs.

Centre of Excellence is more of a system to enable elite athletes to train continuously. Some of them want to continue training without interruption, so those are for that.

Is the Army school boys scheme a success story for SAI?

It's a very good partnership, done very well , best in bouquet of schemes. 99 per cent of kids get into the army by virtue of sports performance. The hardware is army. All funding and coaches are provided by SAI. We are trying to extend it in a very big way. We have gone to the Air Force, Navy and paramilitary.