Amma and I were in Bangalore when death swept through Bhopal on the night of December 2, 1984. The next morning brought tears for her and confusion for me. Three-year-olds do not really understand death. It was afternoon on December 3, when Appa’s phone call finally came through. Amma wiped her tears when he said his eyes were inflamed a bit and that was all. It was later found that his liver function was affected. Over the years, that, too, has become normal. We spent that Christmas together in Bhopal. Amma says it was like the first Christmas all over again, just that there were quite a few Christlike children in the slums and that the trees were decked with curled, black, dying leaves.

Appa stayed on in Bhopal and worked as a social worker among the gas-affected and we joined him for good in June 1985. Among my enduring memories of that time are the empty Liv-52 medicine bottles littering the house and the reek that came off his clothes when he returned from work. We left in 1986, when the Mar Thoma Church called him home to be ordained. I remember marigold garlands tied to the windows of our second-class coach—courtesy of a helpless people who were betrayed by their country and poisoned by Union Carbide (India) Ltd, now owned by The Dow Chemical Company (TDCC). We never went back and did not claim compensation either. But we never forgot. In our family Bible, there is a faded black and white picture of rows of unclaimed bodies lying in front of Hamidia Hospital. How could we forget?

For those who missed the opening scene of India’s worst industrial tragedy: Late on December 2, 1984, Old Bhopal was settling down for a chilly winter night. Most residents had gone to bed. In the illegal settlements around UCIL, poor families pulled tattered blankets around them and settled down to sleep. These settlements had formed when unorganised villagers came to help build the UCIL plant in 1969. The labourers stayed in shacks made of planks and poles, roofed with everything from empty cement sacks to asbestos sheets and sheets of tarpaulin. An ill-fitting reed or wooden door completed most houses.

Unknown to the slumbering city, at around 11:00 p.m. a witches’ brew started bubbling in UCIL’s tank No. E610. The rupture came at midnight. Or according to Dominique Lapierre, at Five Past Midnight in Bhopal. Around 40 tonnes of methyl isocyanate gas escaped from its steel prison. Heavier than air, it quickly settled to the ground, forming a fog of multiple toxic gases. Nudged by a winter breeze, the fog rolled off the plant premises into Old Bhopal. Death was on its way, slowly slipping into houses through chinks, cracks and vents.

People woke up choking, cawing, coughing and clawing at their throats, and the terrified population fled their houses. But death caught up with most. Some choked on their own vomit. Other collapsed as their lungs gave up, and died, red froth bubbling at their lips. Many voided faeces and urine and fell headlong on the road. A few were trampled by loose cattle fleeing the deadly gas. While UCIL puts deaths at around 3,800, other estimates range from 8,000 to over 15,000 immediate deaths. In cases where entire families were wiped out, who would provide the numbers? Many were reportedly buried in mass graves and quite a few were dumped into the River Narmada.

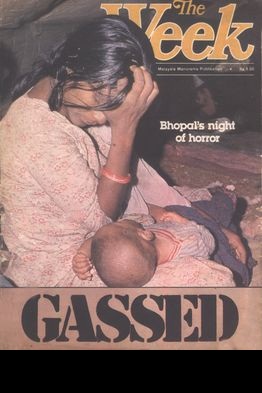

Cover story, Dec. 16, 1984

Cover story, Dec. 16, 1984

A quarter-century later, I visited Bhopal and realised that the betrayal is not over, neither is the poisoning. If Appa’s work was among the gas-peedith alone, Bhopal today has paani-peedith, too—people poisoned by drinking water laced with chemicals. While most of Bhopal has forgotten the tragedy, there is a young generation that carries the poison signature, most of whom were born after the tragedy.

In J.P. Nagar, Fatima Bi does not remember the birth date of her daughter, Shabana Majid Khan, 24. Health worker Tasneem Zaidi, too, was unsure, but said that an Indian Council of Medical Research data card had put it in May 1985. “Fatima’s name figured in the database of women who were pregnant during the gas tragedy,” said Tasneem, who works with the Sambhavna Trust. “We tracked her down and have been treating her and Shabana.”

Fatima said her biggest worry was not about herself, but about Shabana. “I have eight children, five of them girls. She is the seventh. The other four girls were married off between 15 and 19 years. Nothing is working out for her,” Fatima said, pointing at a pale wisp of a girl who quietly slipped down the banister-less stairs.

Not surprising, considering Shabana’s condition. Her periods were irregular and when it came, it stayed on for a fortnight or more. Then there were the recurring headaches, nausea and unceasing waves of dizziness. “Many families make the initial proposal. Sometimes the boy’s ammi [mother] comes. But no proposal moves beyond that,” said Fatima, whose husband died a few years ago from renal failure. Shabana has studied only until class five and said her saddest moment was when best friend Simayla got married. “She was married in Bhopal itself,” she said. “We were pretty close.” She is much better now, and her menstrual cycles are becoming regular. But who will take a chance, in a country where fertility follows dowry and beauty as the most desirable qualities of a girl?

Walking down the alleys of the colony, we ran into a family of gas-orphans. Rekha, 26, was busy washing clothes at the colony’s hand pump. Her brother Jiten, 24, is a ‘gas-baby’, stunted by the poison. Severe polio had crippled their sister Lakshmi, 27. Their parents died on the fateful night and they were brought up by their maternal grandmother. Jiten now works in a shop selling handbags and earns Rs 2,000 a month. I asked Rekha if she was married and where. She giggled and pointed across the alley, as she pushed away a goat that was trying to get a drink from the bucket at her feet. Marriages between gas-affected families are common here and medical experts wince, because the government has no system in place to screen gas-exposed youth and confirm that they do not suffer from possible genetic problems.

If you want to see a man furious about the lack of research on the gas-affected, go to Dr N. Ganesh, who heads the research department at the Jawaharlal Nehru Cancer Hospital and Research Centre, Bhopal. Ganesh’s researches have confirmed chromosomal translocations in surviours and their children.

The condition, in simple terms, causes the merger of two chromosomes, leaving the victim with 45 chromosomes. The common form is Robertsonian translocation which ‘merges’ the five acrocentric chromosome pairs in humans—chromosomes 13, 14, 15, 21 and 22. Unbalanced Robertsonian translocation could cause acute or chronic leukemia, infertility, abortions in the first trimester and conditions like Down syndrome.

“Very few researchers accept that the gas-affected have chromosomal damages,” rages Ganesh. “If you don’t accept this condition, how do you explain the high rate of abortions and cancers among survivors? You are a married man, right, Mathew? What would an abortion do to your family? What would three successive abortions do to your wife? Would you remain sane?”

He recommended exhaustive testing among Bhopal residents and treatment, too. “Let us finish this curse with this generation. In cases like Chernobyl, the governments have tested residents and have put the affected on anti-oxidants, which can effectively scavenge all free radicals. No, it will not cost the Centre millions. Just give our hospital lab Rs 20 lakh and we’ll work wonders. Just Rs 20 lakh! Does the government love its people even that much?”

After seeing the plight of the water-affected, I felt that I must tell Ganesh, “No, perhaps my country does not love its people that much.” Because which other country would leave tons of chemicals unattended in the sealed UCIL? Sources said these chemicals, including heavy metals, have leached into the water sources around the factory, poisoning tube wells in around 14 colonies. When THE WEEK went to the UCIL campus, we found asbestos insulation dropping from pipes, like cotton candy. In the lab, bottles of chemicals were lying around, festooned with cobwebs. Standing close to a set of reactor tanks, I felt an acrid smell. I thought, after all it was 25 years ago and I was imagining things. But then senior photographer Salil Bera turned to me and asked, “Aap ko bhi boo a raha he? [Do you, too, smell the stench?]”

All is not over yet. Dr Ganesh pulls out one last tragic case study from his files—the Siddiquis. “No first names,” he said. The Siddiquis were and are quite rich and had three sons. They decided to get all three married on December 6, 1984. Let us call them Samir, Salim and Salman. They fixed the engagement on December 2. Siddiqui Sr came to know that Salim’s fiancée Noor’s brother was also engaged. A generous man, he requested Noor’s family to let him host the four weddings together. So, on December 2, all four couples came together in the Siddiquis’ Koh-E-Fiza house, 8km away from the epicentre. After the engagement, word came that one of their relatives in the UCIL area had collapsed and died and that a few more were in Hamidia Hospital.

Siddiqui Sr got the boys together and rushed to the hospital, carrying food meant for their guests. They distributed it among the victims and returned at night, coughing and with itching eyes. Happily, the family recovered in two days and the weddings took place on the 6th. Today, Siddiqui Sr is no more. Leukemia claimed him, Salim and Noor’s brother, too. Children born to all four couples have pigeon-chest, some are deaf, others dumb and one has webbed fingers. Dr Ganesh asked, “They dine off silver plates, Mathew. They could afford any treatment. If they were screened and treated, the grief could have been avoided. Do you still want this curse to pass on to the unborn?”