Y.T. Wong, K.L. Yang and K.W. Chen do not figure in the list of Chinese martyrs against imperialism. They lost their lives during World War II. But there are no memorials honouring them in China, not even an epitaph. Their remains, if any, lie in the Himalayas, here in India.

Wong, Yang, Chen and other Chinese men worked as pilots, radio operators and technicians in the China National Aviation Corporation (CNAC), founded by anti-communist leader Chiang Kai-shek. Their mission was to stop Japanese movement towards deep-west China and India. They were as much part of the Hump operation as the Americans who worked for the CNAC, which initially had a partnership with Pan American Airways. They crashed to their deaths, defending their homeland, its neighbour and the idea of freedom.

These unsung heroes—from Beijing, Shanghai and Kunming—were from a heady generation that was celebrating the demise of China’s old imperial and feudal ways and ushering in a liberal era for their country. Many of them wanted to see the world and cared little for military discipline. But destiny had other plans; the CNAC drew them into the Sino-Japanese war in 1937 and eventually World War II.

Owing to war and economic uncertainty, Pan Am stopped backing the CNAC. But its powerful vice president William Langhorne Bond lured some of the American flyers back to China, stabilised Pan Am’s funds for the airline and recruited many more Chinese. Thus, the CNAC was relaunched with a new strategic goal of airlifting for war efforts.

Under this new scheme, cargo aircraft, fully loaded with men and supplies, were expected to fly over eastern Himalayan gorges and canyons—called the Hump—dodging Japanese aircraft that guarded the airspace over Myanmar. These flyers were posted in Calcutta and Assam, from where they flew with supplies and bombs to Kunming. Flying under the banner of 'Free China', which was different from the growing brand of the communist party of China, they acquired fame and glamour. The CNAC, with its dedication to non-communist China, was a strong sign that there were two Chinas emerging as World War II dragged on in southeast Asia. But at one point during its 20-year-long existence, the CNAC had 'China’s Wings' as its logo and claimed to represent all of China and not just the non-communist China.

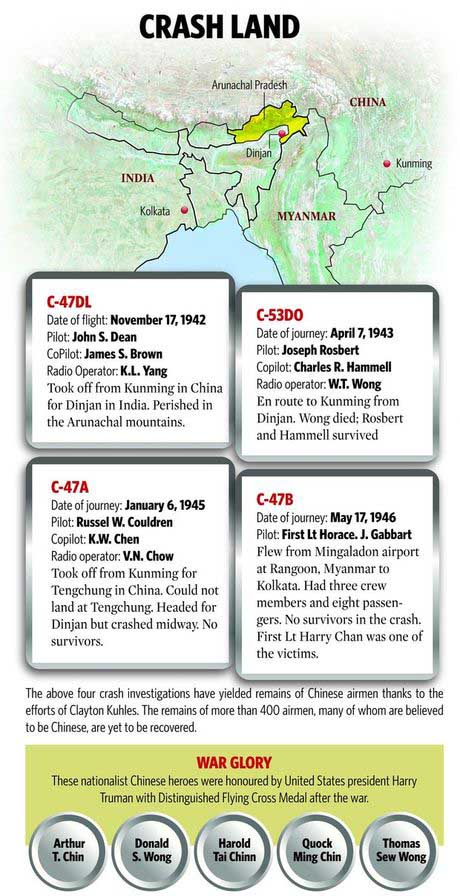

While news of the Americans who died in the air crashes in the Hump operation and demands for the recovery of their remains have been doing the rounds for the last several years, no such demands were heard in China. But Wong was lucky in a way. He was killed in an air crash on April 7, 1943, but the pilot of the aircraft, Joseph Rosbert, survived to tell the story. He came looking for Wong's body in Arunachal Pradesh in 2005. But he could not go to the high mountains where Wong’s body is believed to have been lost. Rosbert spent his last years seeking out Wong’s family in China, and with his demise in 2007, the hope of even remembering Wong is perhaps fading away. Others, however, were not as lucky: their crashes did not leave any survivors.

All that is left of them are black and white photographs of their wild days in Kolkata and winter breaks on Kashmir houseboats, left behind by survivors, asking for recognition and closure. They also continue to live in the memories of those like the centenarian Moon Fun Chin in San Francisco, who also flew over the Hump.

But why is the current Chinese government reluctant to acknowledge its martyrs? The reason is politics, says Angie Chen, daughter of a nationalist Chinese who was part of the air operation. “The communist China versus nationalist China remains a major issue when it comes to evaluating Chinese history of World War II, and that is why claiming these victims is not easy for the present Chinese regime,” she says.

These Chinese men and their historic role would have remained buried in the Himalayas had the geopolitical forces not pushed them to the forefront this year. During President Barack Obama's visit to India in January, a joint statement was issued. Hidden in the 5,754-word statement was one sentence that said India would facilitate humanitarian mission to recover America’s Missing in Action (MIAs) who crashed in the Arunachal Himalayas during World War II.

The declaration came as a sign of government-to-government commitment to an ongoing non-governmental effort, which has been primarily led by Brooklyn-based Gary Zaetz and his organisation, Families and Supporters of America’s Arunachal Missing In Action. Zaetz’s efforts have been mainly aimed at the recovery of the remains of his uncle—First Lt Irwin Zaetz—and other aviators like him who perished in the mountains across the rapidly-developing Tezu airport in Lohit district of Arunachal Pradesh.

Zaetz was helped by Clayton Kuhles, a famed Alpinist, who trekked in the Himalayas in search of crashed aircraft. After several treks by Clayton and based upon the US Department of Defense estimate, it has been assessed that the Hump at present is alive with the remains of more than 400 aviators who perished in World War II. Kuhles has trekked to 22 crash sites so far and his reports, put up on his website miarecoveries.org, reveal that almost all the crashed aircraft had one or more Chinese nationals in them. The Department of Defense estimate shows that nearly 90 aircraft belonging to the CNAC crashed in the Arunachal, and Kuhles's report gives the indication that a large number of those 400 MIAs were Chinese.

Santanu Kri, a historian of the Mismi community that resides in the crash-dotted eastern Himalayas, says that there are strong emotional bonds that bind the US with nationalist Chinese movements. “The sentence in the joint statement clearly reminds the Chinese that the communist China did not win the battle against the Japanese all by themselves and that the sacrifices made by the non-communist forces cannot be forgotten,” he says. “Without the successful airlift across the Arunachal Himalayas by the CNAC of Chiang Kai-shek, the Japanese could not have been dislodged from southern China and northern Myanmar, and India could not have been secured during World War II.” The symbolic value of the remains, he says, will provoke uncomfortable questions from the younger generation of the Chinese to their communist masters about the role of the nationalist Chinese in the liberation war of the 1940s.

Santanu Kri | Arvind Jain

Santanu Kri | Arvind Jain

This political difficulty inside China over the remains is evident because there has been no civil society-led attempt there to highlight the Chinese martyrs. And the Chinese have been rather cautious in dealing with Zaetz's insistence on greater support for his campaign.

The 400-plus graves in the crash sites in the Arunachal Himalayas are, however, just one-fourth of the total casualties of the CNAC flyers. More than a thousand, many of them of nationalist Chinese, are located in the southwest Chinese territories and in the mountains of northern Myanmar. “The graves in China and Myanmar are yet to be explored but we hope they will be made free for recovery in future for humanitarian reasons,” says Zaetz.

India received first-hand information about the tussle between the Communist Party of China and the nationalists, human rights and anti-corruption crusaders on May 19, 2010, when a Chinese national was arrested in Tezu. The Mismi tribe was alerted that China had begun perceiving the zone near Arunachal border as a problem area owing to the fact that a large number of dissidents wanted to access this remote but well-developed area on the Indian side to escape one-party rule at home.

The intruder, Guang Liang, was convicted under the Indian Foreigners Act. While in custody, he narrated tales of torture of political rebels and the nationalist critics of communist China. He informed the Indian investigators that the Chinese government had been cracking down all the way from Shanghai and Kunming to the mountain passes that led to Arunachal in search of nationalists like him who did not share the communist ideology.

Kri, who met Liang, says: “His account of persecution highlights that the legacy of Chiang Kai-shek remains a taboo in China and a lot of the hate for India among the Chinese communist party hardliners, perhaps, comes from the fact that the nationalists of China had a great relation with the freedom fighters of India.” Liang spent 30 months in custody, following which he was reportedly handed over to the Chinese in a secret diplomatic deal. However, the Arunachal government is yet to prepare a formal closure note on the case.

The crashes have never been fully rationalised. Why so many aircraft crashed in a span of two to three years is also not known. However, anyone visiting this region can see that the atmospheric pressure remains low often causing stormy weather, which probably made low-tech transport and bombers of the World War II era an easy prey to the elements.

The crash sites are also significant from the strategic point of view for India. From east in Changlang and Kibithu to the mountains west of Tezu, the crash sites on the Hump form a complete array of spots that cannot be dealt with in a fleeting humanitarian operation. Such an operation will require long-term presence of men and machine to recover whatever physical and mechanical remains can be gathered for the family members of the fallen heroes.

“The Americans are obviously eager to build nestling spots in the eastern Himalayas where they have the emotional linkages dating back to the days of the crashes of the 1940s,” says Brig (retired) Gurmeet Kanwal, who has served on the India-China border near Dong, the easternmost village of India.

One interesting development, however, is that the mountains have considerably been tamed by Indian efforts. Proof of this taming can be seen in the hectic work under way at the Tezu airport, which has been upgraded and is undergoing finishing touches to host not just big civilian aircraft but also heavy-lift and long-distance bombers if the need arises. The airport of Tezu is not the only new show of muscle that might help any future attempts for rescue and recovery of the MIAs. India is further strengthening its defences by building a high-altitude strategic airfield in Walong, which is located in Anjaw that borders China. Walong, Hyuliang and Kibithu were three of the spots of fierce fighting during the 1962 India-China war. But infrastructural development and military buildup on the Indian side show that a future military challenge from China will be met by a tougher India.

Kanwal and Kri see a great game, a long-term implication, in the key recovery-related sentence in the joint statement by Modi and Obama. They say it has hinted at tickling China’s prickly history. Kri says that mentioning the recovery operation in the joint statement was a good move by India as it cuts the shrill Chinese demand on Arunachal Pradesh.

Gary Zaetz

Gary Zaetz

Mamang Dai, Arunachal’s leading writer, says that by acknowledging the US’s long-term ties with the northeastern mountains, India has shown its desire to play a great game in the northeast if the Chinese pressure becomes too much to bear. “Otherwise, there was no need to disturb the graves which have been transformed into ingredients of folklores of various tribes of Arunachal over the past seven decades.” The other worry, Dai says, is that the advent of so many outside forces might also trigger a backlash, which will have to be factored in before unleashing military might in the form of “humanitarian operations”. She says that the Americans have been looking for a foothold in the eastern Himalayas for a long time and that the Tibetans are another strong reason for them to come in.

The Tibetan angle of the great American game on China is aptly summed up by the 85-year-old Dhondup Palden, a Tibetan settled in Tezu’s Lama Camp neighbourhood: “I dream of fighting in my sleep. I see firing automatic guns against the Chinese soldiers in Lhasa. I was trained for war and I am still a fighter in my heart.” Palden, a devout Buddhist, was one of the thousands of Tibetans who were trained by the Central Intelligence Agency of the United States in the 1950s to fight against the Chinese forces who occupied Tibet.

The remains of the CNAC aircraft and their American and Chinese crew have been discussed between the Indians and the Americans since 2008 when the Indo-US Defence Policy Group met in Washington, DC. India had pledged to begin humanitarian recovery operations to bring closure to the families of the American flyers. That agreement was revived in the 2012 meeting between defence secretary Leon Panetta and defence minister A.K. Antony. After a few preliminary trips to the graves, India stopped the exploration in November 2014.

But the Modi-Obama joint statement has once again highlighted the fact that the Chinese find their own history inconvenient as that might bring problematic information for communist rulers in Beijing. As of now, Americans like Zaetz and a large number of members of the CNAC Association are vocal about recovering their fallen from the eastern Himalayas but China has neither announced the number of Chinese men missing in crashes in Myanmar and northeast India nor praised the CNAC's glorious role in anti-colonial struggle. The association of CNAC workers will hold their next meeting this autumn. It is just a matter of time, they say, before they bring the Americans home to their final resting place. It remains to be seen how the Chinese will then treat the likes of Wong who never made it home.