A 100km drive from Rishikesh takes one to Srinagar in Pauri Garhwal district, Uttarakhand. It is the last town in the plains. From here, the majestic mountains rise.

It is twilight, and the rays from the high-power bulbs at the Srinagar power project dam site gleam through the fog down the valley. The private project, which can produce about 500MW power at full capacity, hardly produces 125MW. And Srinagar suffers a five-hour power shutdown every day.

As I enter the town, images of the devastating floods of June 2013, which swept away more than 5,000 lives, flash across my mind. This was one of the towns that were hit by water and rubble with the intensity of tonnes of explosives.

At night, there is no power supply in the guest house of Hemwati Nandan Bahuguna Garhwal University. The battery backups, too, give up soon. The only things visible from the balcony are the powerhouse sites. The rest of the town around the dam, on both sides of the Alaknanda river, looks painted in black.

The floods had wrecked this university; a large part of the campus is still ‘missing’. Unscientific diversion of the river into tunnels leading to private turbines turned the natural disaster into a catastrophe, says the university’s geology department.

“The main problem is that there are large-scale violations of norms and major variations from the detailed project reports,” says Prof S.P. Sati, who studied how leftover construction material and rubble from the stone crushing sites turned deadly for the town. “We waded out of ten lakh cubic metres of muck after the floods.”

As per geological specifications, the area above Kedarnath is referred to as upper Himalayas. Most of Uttarakhand’s dam projects are located in this region. “The upper Himalayan terrain is more sensitive, but they have dams even in the Nanda Devi Biosphere Reserve,” notes Sati. “With loose sediments in huge quantity and heavy water flow, the higher terrain is a time-bomb ticking away.”

It is 5pm in Joshimath, 6,150ft above sea level. Courtesy frequent rains and power outages, most shops in the market down their shutters by sunset. A little uphill, I meet Atul Sati, who spearheaded a statewide agitation against dams in 2004-05, in his single-room, candle-lit office.

“Uttarakhand is the water bowl of India and the state government wants to make it the power hub in the Himalayas,” he says. “But even if that is achieved, Uttarakhand will still remain in the dark.”

Most power-producing companies here were accommodated under the 2002 Electricity Policy, which identifies public and private players as “independent power producers”, who took up projects on a 45-year lease. They are mandated to distribute just 12 per cent of the power free of cost to the state.

“That means the companies can sell 88 per cent of the power produced outside Uttarakhand in cities such as Delhi, Lucknow and Kanpur,” says Atul Sati. “The cost of development in the cities will always have to be borne by people in the hills.”

The people of the hills have long been opposing the mega projects. After all, this is the land of Chipko Movement founder Sunderlal Bahuguna. Atul Sati’s movement, for instance, did not allow former Uttarakhand chief minister N.D. Tiwari to inaugurate a hydel power project in Joshimath. Tiwari inaugurated it in Dehradun for fear of a public backlash at the site.

“We are not against development,” says Atul Sati, even as he shows cracks on the walls of his room. “The state-appointed Mishra Committee had said in the 1970s that the loose soil here might not support large infrastructure such as dams. Joshimath, which is sinking at a rate of 2ft a year, has been affected because of massive constructions in and around the town.”

The 450MW Vishnu Prayag project, run by a private power company, is located at the base of the Joshimath hill, along the Dhauli Ganga river. The project started in 2005, despite public protests. Its turbines are linked to 12km-long tunnels drilled through the mountains.

Four such tunnels passs through Chai village in Joshimath. “We lost our streams. Our crops and animals have suffered; the cows don’t give enough milk as they don’t get sufficient water,” says Dinesh, a villager, who treks 7km to graze his cows.

Dinesh is not alone in angst. Most men of this once agrarian village have taken up farm work elsewhere.

The walls of their houses reflect the state of life here: cracked. “Officials from the power project visited the village many times until a few years ago. But, we have not received any assistance for rebuilding our houses,” say Seema and Sushila, who seem to have lost hope.

What an irony! The tunnels for power generation run under their feet and the power-transmitting lines run over their heads, but the 550 villagers here have no access to electricity.

Worse is the case of some villages near Rudraprayag town. People here are now forced to request the nearby hydel projects to release water from the dams at specific times, so as to carry forward their tradition of immersing the ashes of their loved ones in the river.

The tunnel expansion works are another headache for people near power project sites. “They blast [dynamites] at 2am and 3am. We can’t sleep here at night; everyone is leaving this place,” says Latika Punwar, a student in Joshimath, where two projects are being run by the National Thermal Power Corporation and a private company.

The NTPC’s Tapovan project has a 14km network of tunnels snaking beneath Joshimath and 12 smaller towns and villages around it. In 2007, the engineering contractors appointed by NTPC for the project, Larsen & Toubro, hit an aquifer.

With water gushing in at 600 litres per second, the tunnel was inundated. An Australian drilling machine, which was deployed, stalled, and it still remains stuck down there. Reply to an RTI query says NTPC is still figuring out ways and means to revive the project.

A smaller project, but important because of its altitude and ecological sensitivity, is NTPC's Lata-Tapovan project on the way to the 'future abode' of Lord Badrinath, Bhavishya Badrinath. While assessing the impact of the project, the Geological Survey of India had noted the presence of a hot spring near the river. It mooted the idea of using such thermal springs as perennial sources of geo-thermal power, but the proposal fell on deaf ears.

The Lata-Tapovan project is one of 24 dam projects, in the higher reaches of Uttarakhand, which have been stayed by the Supreme Court.

Experts say the channelling of river water into tunnels can have adverse effects. “The water that passes through the turbines lacks dissolved oxygen, so the first impact is seen on aquatic life in the region,” says Parthasarathi Datta, former director of the Nuclear Research Laboratory, Delhi, who is now an independent adviser on water and environment. “Rubble from the blasts and concrete construction on the river bed add to the bio-stress factor.” Datta believes that the 2013 tragedy in Uttarakhand was manmade. He doubts whether there was a cloud burst at all before the floods.

“Meteorologists use ‘cloud burst’ as a general term,” he says. “So far, there are no global or Indian studies available on cloud bursts, except a mention of the term in half a column in an article carried by the scientific journal Nature in 1954.”

At a presentation made to the International Association of Engineering Geology, Italy, Datta raised the same point. “Two glaciers near the Chora Beri lake join at the confluence of the Mandakini river. A private power company erected a moraine barrier across the river some days ahead of the flood to assist construction work downstream,” he explains. “At night, when heavy rains occurred, this barrier gave way and that triggered the floods. The large volume of water changed the river’s natural channel dimensions.”

Crack, no joke: Atul Sati, leader of an anti-dam movement, shows a crack on the wall of his house in Joshimath | Sanjay Ahlawawt

Crack, no joke: Atul Sati, leader of an anti-dam movement, shows a crack on the wall of his house in Joshimath | Sanjay Ahlawawt

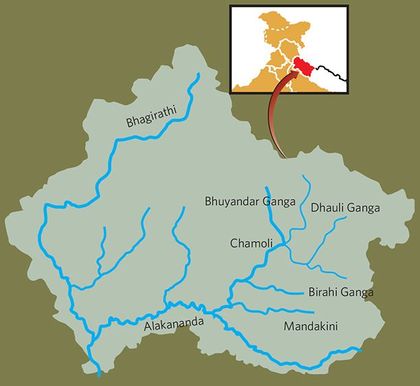

A recent study by the Alternate Hydro Energy Centre of IIT Roorkee says that, on completion of all the proposed hydroelectric projects in Uttarakhand, about 70.71 per cent stretch of the Bhagirathi river, 48 per cent of the Alaknanda river and 93.6 per cent of its main tributary, Dhauli Ganga, will be trapped in tunnels and reservoirs.

A 2013 study by Kathmandu-based International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development highlights that the rate of glacial melt in the Himalayas has increased by three times in the past 100 years. River volumes have increased by up to 200 per cent of what was measured just 10 years ago.

“The problem is that most of the hydroelectric projects have been built considering the historical data of water flow in these rivers and the belief that the flow will remain the same,” says Datta. A sudden surge in water levels could cause more devastation, he adds.

After the Tehri Dam, the second largest dam in Asia, submerged Tehri town and 37 villages, displacing more than 10,000 people, N.D. Tiwari declared in 2003 that the state would not allow construction of big dams. Subsequently, the hydel projects in the state started drilling tunnels through the mountains to channel water into their turbines. In 2007, chief minister B.C. Khanduri, too, took a stand against big dams.

However, work on the Indo-Nepalese Pancheshwar Dam—about three times larger than the Tehri Dam—is under way for a 6,480MW hydel project, which will submerge 120sqkm in Uttarakhand and 14sqkm in Nepal.

“Uttarakhand had seen seven chief ministers in fourteen years. The focus on development has remained skewed, when it comes to taking a stand on the increasing number of hydel power projects. The point of sustainable development has been completely missed,” says Anil Joshi, founder of Himalayan Environmental Studies and Conservation Organisation. “The impact of such projects and dams is being felt by people everywhere in this part of India—Himachal Pradesh, Jammu and Kashmir and the northeast. Incidence of landslides and flash floods has increased considerably because of hydro projects.”

He cites studies and warns of a Nepal-like devastation in the state. “The insensitive development in the name of power and the heavy pilgrim rush are taking their toll on the local people,” he says.

Water will be on the boil during 2017 assembly election in Uttarakhand. Though the Congress government in the state is backing power projects in the ongoing case in the Supreme Court, local party leaders slam them.

The Union government, too, has been making flip-flops in court. In an affidavit submitted on May 11, the Union environment ministry said an “expert body” would study the February 2015 report by a government-appointed four-member committee on clearances to six projects, which were blacklisted after the 2013 floods. The court had asked the ministry's views in December 2014.

The movement for Aviral (undisrupted) Ganga was started by Swami Nigamanada of Matri Sadan ashram in Haridwar. The 34-year-old monk, referred to as Gangaputra, died in 2011, after fasting for 115 days to protest illegal mining of riverbeds. Later, many monks joined the movement, seeking protection of rivers.

“In 2013, the Supreme Court set out to ascertain if the disaster [2013 floods] was manmade. That is when we filed our first affidavit,” says Swami Samvidanand, of Abheda Ganga Maiya Ashram in Haridwar.

The movement's efforts to apprise the “highest authority” about the situation in Uttarakhand have gone in vain so far. “Since Narendra Modi took office in May last year, we have been trying to meet him. But he has not agreed to meet us,” says Samvidanand.

The movement leaders, however, were able to meet BJP president Amit Shah. When told about the BJP’s lack of support and the government’s U-turn on the hydel projects, Shah reportedly quipped: “Hum dono ek hi hai (We both are the same)!”

Water Resources Minister Uma Bharti, who had backed the Aviral Ganga movement, told the monks that she was helpless, and ready to resign if they demanded. “What else can I do?” she apparently asked them.

Even as the debate over power projects is heating up, Uttarakhand is struggling with an annual power deficit of 4,000 million units. “Our power deficit is about 30 per cent. From all the hydel projects functional in the state, we are producing about 8,000 million units; rest we procure from the open market [at Rs900 crore a year],” says Uttarakhand power secretary Umakant Panwar. “We are looking at procuring gas from Uttar Pradesh and generating about 500MW from gas plants.”

Another major concern is Uttarakhand's tourism industry. “It is worth Rs34,000 crore,” says Atul Sati. “Building dams in the hills will kill tourism.”

Datta believes solution lies in having smaller projects (less than 10 MW), while scientists such as Datta say only ethical practices and honest environment impact assessments can save the Land of Gods.

Interview/ Harish Rawat, chief minister, Uttarakhand

Is it our fault that our land is the Ganga's birthplace?

By Soumik Dey

How grave is the problem of power shortage in Uttarakhand?

We have a power deficit of about 800MW. The capacities that we wanted to upgrade have been stopped [by a Union government order]. Otherwise, the state would have ended up with 1,200MW surplus power.

The government order on the eco-sensitive zone was issued UPA 2. Why are you opposing that now?

During the Congress rule at the Centre, it was decided we would not notify this [the order] in the state. We amended local laws. We had decided that we would let it [the order] die it's own death.

But, all of a sudden, a new notification was thrust on the state, and the eco-sensitive zone area has been increased by 100 times from what was suggested in the draft proposal.

Your position in the Supreme Court is contrary to the empowered committee's view on Uttarakhand's unique ecological position.

The expert committee's views have not been endorsed by committee members from power utilities. In fact, they have opposed the views. Second, there were other government of India expert committee studies as well. Then, there is a study by the H.N. Bahuguna University. They have all said hydro power will not have any effect on the ecology. I am just a layman. But, I am sure, more than sure, that water is good for the ecology. The food chain gets disturbed without water. Yeh ek layman ka understanding hai.

Tunnels for power projects in the higher reaches are said to be drying up aquifers.

That is there. I think for this we need to have sustainable plans. We have to find a solution. Koi phoda jab ho jaye to uske liye haath thodi kaat dete hai. Us phode ka ilaaj kar denge. (You don’t cut your hand when suffering from a blister; you rather apply some medicine).

Do you expect support from the Union government in the Supreme Court case regarding stayed hydel projects?

I believe the Centre will now have to do a rethink. How can you single out Uttarakhand when you have dams in every other state? Is it our fault that our land is the birthplace of the Ganga and Yamuna. Why penalise us? Why is everyone telling us to stop [hydel projects]? If it is poison for me, why is it amrit for Chhattisgarh or any other state?

Some sections in the BJP say these hydel projects and their tunnelling could dry up Ganga and Yamuna.

Of course, they would not dry up. They are not going away anywhere. The BJP is misinforming and playing with sentiment of people over the issue of aviralta (continuity) of Ganga. Let me tell you, there is no dam in the world that has ever been able to stop the natural flow of a river to zero.

Power plague

June 2013

Flash floods kill more than 5,000 people in Uttarakhand. Some experts and activists blame the numerous dams built across the state's rivers. A 2010 CAG report, in fact, had criticised the state for “indiscriminately” pursuing hydropower

August 2013

The Supreme Court bans new projects. It directs the Centre to set up an expert committee under environmentalist Ravi Chopra

April 2014

The committee flays 23 of 24 proposed dams; these dams were red-flagged by the Wildlife Institute of India

May 2014

With two reports in hand, the Centre seeks another review. The court questions the need for another committe; continues ban on 24 proposed projects.

August 2014

The Centre seeks more time. The court asks for reports on each dam

October 2014

The NDA government does a U-turn; says the proposed projects can be fixed

December 2014

the Centre says many analysts have warned of dangers of projects; seeks another year for thorough assessment. The court seeks the government's views on six specific dams for now

February 2015

A government appointed expert panel says the six projects pose a high threat

March 2015

The environment ministry, however, submits an affidavit overruling the ecological risks from the power projects

April 2015

The ministry seeks more time to reply to the Supreme Court's queries, as the prime minister is not available for deliberaton. The court shifts hearing to May 10

May 13, 2015

The Union government tells the court that it plans to set up another expert panel to study all projects on the Ganga basin in Uttarakhand