When Kailash Satyarthi was on the podium at the Oslo City Hall for his Nobel lecture he realised he had misplaced his notes. He was nonplussed for a moment, but recovered quickly. “Initially I spoke in Hindi. Then I told the audience that I had lost my notes. In fact, I felt more comfortable without them,” he said. By the time the organisers brought another copy of the notes, neither Satyarthi nor the audience needed it.

Now, six months after winning the Nobel, Satyarthi, 61, remains equally at ease with the attention it has brought. Many things, of course, have changed—like his phone; the old Nokia has been replaced with the latest iPhone, which was gifted by his son. Though he accepted it reluctantly, now he enjoys taking photographs with it. He always had a penchant for photography, but never bought a camera because he could use the money in more meaningful ways.

Satyarthi's life is a lot busier now. His office in Kalkaji, Delhi, receives thousands of invitations every day. “If I don’t accept any invitation from today, it will take me around 75 years to wind up the current ones,” he said. On an average, he travels 20 days a month. Even earlier he travelled a lot. But, it is different after the Nobel. The award has catapulted him to business class. “I was not used to business class luxury and being treated as state guest,” he said. “But now I’m trying to get into that mode. I am surprised to see that how a Nobel winner is respected.”

In Orlando, US, when Satyarthi attended an Indian doctors’ conclave, a doctor couple brought their baby to him. They wanted him to bless their son. “I thought I was neither a priest nor a magician, how would my touch make a difference. I took the baby in my lap and the couple was overwhelmed. There I realised how much respect is being accorded to me after the Nobel Prize.”

The biggest change of his life after the Nobel, however, is that his words and deeds are being taken seriously. His causes—elimination of child slavery and trafficking—have found place in the agendas of policymakers. “Earlier there was no hope,” he said. “The efforts were unacknowledged and unrecognised. After I got the prize, an atmosphere of hope is building up worldwide.”

And, with the growing hope comes a bigger responsibility. “After the prize I feel that the moral pressure has gone up on me. I feel that each minute of my life I should devote to these children. I am trying to get adjusted to this new life,” he said. Now he discusses policy issues at the highest level. He has been heard by most heads of state and many world leaders. They have all admitted that there is a need to work together on child slavery and trafficking. Deriving such a global consensus has been a major breakthrough for Satyarthi.

Thanks to his efforts, India government is planning to amend the Child Labour Act of 1986. But, Satyarthi wants more. “If the government passes child labour prohibition act in Parliament, removing the present grey areas, it would be great,” he said.

Satyarthi has kept neither the Nobel medal nor the hefty prize money. He gave the medal to the president, and it is currently at the Rashtrapati Bhavan museum. Some of his relatives, who wanted him to keep the medal at home, were upset. “Had I kept it at home I would have been constantly thinking that some day it might get stolen,” he said. Also, he donated the lantern he had used as a child to a museum in Norway. He gave the Nobel Prize money to charity.

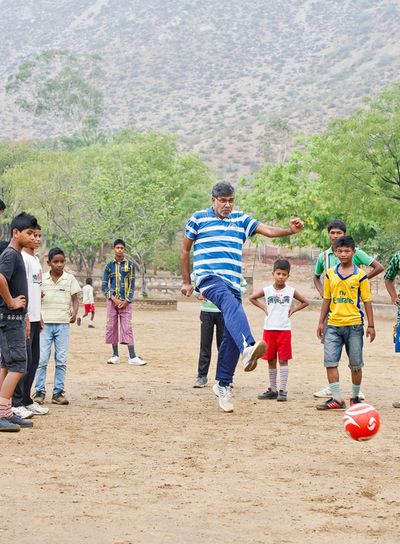

The time Satyarthi spends with rehabilitated children at his Bal Ashram in Viratnagar, Rajasthan, is what he relishes the most. Here he cooks, jogs, plays with children and enjoys music with his wife, Sumedha. “I cook Indian dishes well, besides pasta,” he said. His friend Omprakash Srivastava, who has known him for 50 years, vouches for his culinary skills. “Earlier he would cook my favourite dishes. Now whenever he gets time he does so,” said Srivastava.

Home sweet home: The time Satyarthi spends with rehabilitated children at Bal Ashram is what he relishes the most | Sanjay Ahlawat

Home sweet home: The time Satyarthi spends with rehabilitated children at Bal Ashram is what he relishes the most | Sanjay Ahlawat

Satyarthi was in the kitchen when a journalist friend called and told him that he had won the Nobel. The journalist was so excited that Satyarthi could not understand what he said. “I thought that someone had got the Nobel and the scribe wanted my reaction,” he said. “I searched the internet, and Google showed my name. I was dazed.”

Two incidents in his formative years shaped Satyarthi's life. On the way to his first day at school in Vidisha, he noticed a cobbler and his son polishing shoes. “I felt it a bit strange,” he said. “I asked the headmaster why the child was not studying with us. He said it was a poor child and it was common that he did not study but worked.” Not satisfied with the answer, Satyarthi asked the cobbler why he did not send his child to school. “His reply jolted me. He said he never thought about that and they were born to work. Then I found many children like him. I felt it was injustice,” he said. It sowed the seeds of his efforts to uplift underprivileged children.

The second incident happened in 1969. It was Mahatma Gandhi’s birth centenary. Satyarthi, then 15, planned a community dinner as part of his fight against untouchability. Local leaders were expected to dine with the lower castes and eat food cooked by them. The dinner was arranged at a park near a Gandhi statue. As no leader turned up even after the scheduled time, Satyarthi went to their houses. While some of them again assured him that they would come, others gave lame excuses. Ultimately no leader came. “I felt betrayed, and I cried,” he said. “While I was quietly having food with them, I felt a soothing touch on my back. It was an old lady. The touch of that untouchable rid me of my pain.”

His relatives, however, were not amused. “They were angry that a Brahmin boy broke the caste system and had food with the untouchables,” he said. They wanted to purify him and asked him to wash the feet of 101 Brahmins, drink the water and shave his head. He did not budge, and they ostracised him. Satyarthi revolted; he dropped his surname that carried the Brahmin stamp. That is how Kailash Narayan Sharma became Kailash Satyarthi.

Though a believer, Satyarthi does not go to temples. “I could see glimpse of God in the faces of these free children,” he said. “This is the easy way to be close to God.” His goal is to ameliorate the condition of ten crore deprived children around the world. For this, about ten crore children will act as their spokespersons and tell the world about their plights and rights.

Satyarthi dreams of a day when every child is free to be a child—free to laugh and cry, free to play and learn, free to stand on his feet and reach for the sky. “Whenever I rescue a child, the first smile of freedom on his face gives me a divine feeling,” he said.

In his work, Satyarthi has always been ahead of his times. He began the fight for child rights a decade before the UN thought about it. He made use of the concept of corporate social responsibility long before it became an in thing. “He does not think for the coming five years; he has a great vision and he thinks about generations ahead, and how children can participate to make future generations better,” said Rakesh Sainger, a director of Bechpan Bacho Aandolan, who has worked with Satyarthi for more than a decade.

Satyarthi is worried about the increasing cases of violence among the youth and said it would be difficult to control them. “Today’s environment is disillusioning the youth. Their desires are big; they are insecure, and politics worldwide has become fanatic. In such an atmosphere, my efforts would be to save them from moral pollution,” he said.

And, people are expecting a lot from him, especially after the Nobel. “Kailashji has the power to convince people. Still he works tirelessly. Now people have high hopes and we need to work harder to deal with the problem of child slavery,” said Rama Shanker Chaurasia, who has been working with Satyarthi for the past 33 years.

Sumedha shares the burden of the work with Satyarthi. Called 'mata (mother )' by the inmates and staff of the ashram, she is in charge in Satyarthi’s absence. As she is from a family of freedom fighters, she never found it difficult to adjust herself to Satyarthi’s routine. “I was used to visitors, frequent cooking and many rounds of tea,” she said. Sumedha has been an integral part of his struggle to eradicate child slavery. She took part in many raids and rescue operations with him. “His simplicity attracted me towards him and, ultimately, God wanted us to meet,” she said. Their son helps Satyarthi with the legal affairs of his organisations, and their daughter is a homemaker.

Small successes make Satyarthi happy. He knows he can multiply them. The Nobel was a turning point. While he took the turn happily, the journey continues.