For an octogenarian, Alok Krishna Deb is in pretty good shape. A former athlete, he was good at long jump, high jump and pole vault. Even today he skips a few steps as he climbs to the top floor of his four-storey building in North Kolkata's Shovabazar. When it comes to family matters, however, this Shovabazar royal will not skip even the smallest stone.

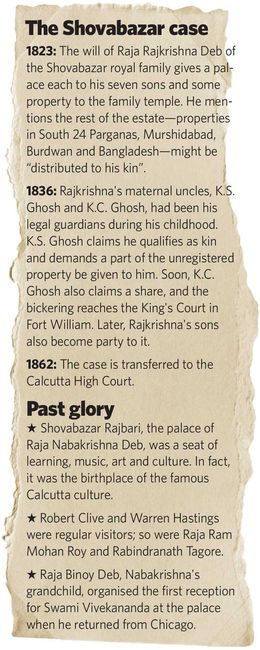

Deb is inflexible in his determination that the royal family will never accept defeat in a case that is a century older than him. The case started in 1836 over an inadequate will left by Raja Rajkrishna Deb, son of the family's founder Nabakrishna. It could well be among the oldest legal battles in the world. And, an end to it still seems distant.

“The case is a prestige issue for us which our forefathers had fought during their lifetime. We should not be an exception. It has become a tradition for us, like our dress code and living standard,” said Deb. The Calcutta High Court hears the case once or twice in a decade. The last hearing was in 2009, when one of the two court-appointed receivers died. The value of the estate under dispute is estimated to be around Rs.4,000 crore.

Nabakrishna, who hailed from Murshidabad, was an employee of the English East India Company. He had a sharp mind and deep understanding of the British culture, and he knew English, Farsi and Persian. He was elevated to a top position in the company after he helped it recruit workers in Bengal. He became a close adviser of Robert Clive and helped Clive defeat Siraj ud-Daulah in the battle of Plassey in 1757. Nabakrishna was rewarded spectacularly―he was made the dewan of Sutanuti village of Calcutta. The villages of Sutanuti, Gobindapur and Calcutta constituted the city then.

A visionary, Nabakrishna built what is North Kolkata today. At home, however, he was a disturbed man. He got married as a teenager, but did not have children. So he adopted Gopimohan, a nephew, as his son. Later, Nabakrishna married three more women, and had a biological son, Rajkrishna, in his third wife.

“The unfortunate part was, his adopted son, who was well established by then, did not accept it,” said Deb. Nabakrishna, who had become weak by then, was worried about the safety of his newborn, and he sent Rajkrishna to the boy's maternal uncles' house. The uncles, K.S. Ghosh and K.C. Ghosh, looked after him.

“Gopimohan bargained with Nabakrishna well,” said historian Amiya Nath Maity. “If Nabakrishna could deal with family matters with the same efficiency he had with the East India Company, there would not have been any trouble.”

Nabakrishna divided his estate equally between the adopted son and biological son. However, Gopimohan, who stayed with the father, had the opportunity to choose his share. Though Nabakrishna ruled only Sutanuti, he had properties all over Bengal. According to the will, Gopimohan received most of the land in Sutanuti, Gobindapur and Calcutta, and his descendants were left with no trouble.

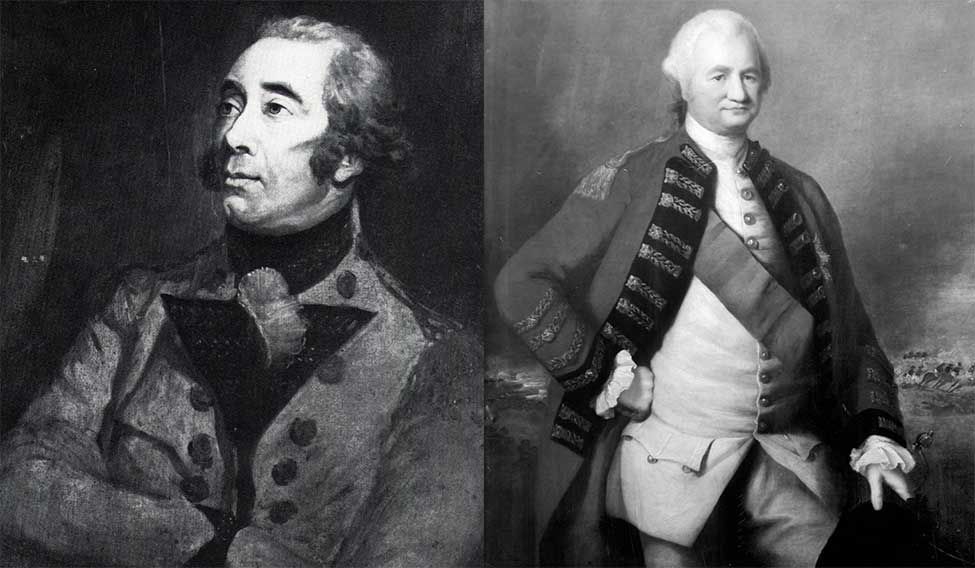

Nabakrishna had close associations with Warren Hastings and Robert Clive | Roger Viollet

Nabakrishna had close associations with Warren Hastings and Robert Clive | Roger Viollet

Rajkrishna received some houses in Sutanuti and most of the rural properties. A significant part of this is now in Bangladesh. This and Nabakrishna’s admission of the Ghoshes as legal guardians of Rajkrishna (he was minor when the will was executed) became the core of the legal battle later.

Nabakrishna, who died in 1797, was a patron of art and culture. Though deeply religious, he had a secular outlook. He gave the land for St John's Church, one of the oldest in Calcutta. Rajkrishna continued the legacy. He helped build many mosques and churches in the city, and made his palace the nerve centre of art and culture.

Unlike his father, however, Rajkrishna was a happy family man. He had seven sons. Some historians say he was so enamoured by Islam that he chose a Muslim girl as one of his wives. His life, however, did not last long. He died in 1823, at the age of 41. In his will, he gave seven palaces to his seven sons, and allocated some property to his family temple. He mentioned the rest―properties in South 24 Parganas, Murshidabad, Burdwan and Bangladesh―might be “distributed to his kin”.

According to historians, this was the seed of the legal battle. Since Nabakrishna himself mentioned the Ghoshes as Rajkrishna's legal guardians, K.S. Ghosh demanded that a part of the unregistered property be given to him. Soon, K.C. Ghosh also wanted a share, and the bickering took a legal turn when it reached the King's Court in Fort William in 1836. The case was registered as Ghosh versus Ghosh. Later, the sons of Rajkrishna also became a party to it, as they did not want to share the estate with the Ghoshes.

The King’s Court, which was the Supreme Court in Calcutta, found the matter controversial as it involved the property of a king. It passed the case to the Privy Council in London. But the Council declined to take a decision on it. “So it was sent back to the Supreme Court in Calcutta. When the Calcutta High Court was established in 1862, the Supreme Court sent the case to the High Court after 26 years of hearing,” said Deb.

Shortly after taking over the case, the High Court appointed a receiver to look after the property. The court refused to distribute the property to the sons of Rajkrishna even after the Ghoshes died, and appointed British legal luminary Elliot Macnaghten, who was president of the Indian Council, as the receiver.

Maity said it showed the regard the British empire had for Nabakrishna. “One of the foremost legal luminaries of that time looked after his properties,” he said.

Nabakrishna and the British shared a special bond. “He signified Calcutta to the British,” said Tirthankar Krishna Deb, a member of the royal family. According to family records, Nabakrishna received 10,000 horses, as many sepoys, thousands of elephants and hundreds of guards from the East India Company when he became dewan. Tirthankar said the court should have ended the case by distributing the estate among the inheritors so that every generation of the Debs did not have to spend money to continue with the litigation.

That the court is yet to resolve the case is baffling. Many historians say the court wanted to make the property a monument. “As years passed, British judges in the High Court thought the litigation had become a heritage litigation. So they tried to protect the property as a monument,” said Maity. And, with the death of the Ghosh brothers, the chances of an out-of-court settlement vanished.

In 1888, after the death of Macnaghten, the court appointed another receiver. Many more receivers followed. They collected taxes from the occupants and paid it to the government. In 1956, the government acquired a part of the estate through an act. Later, the court asked the government to release a part of the litigated property as well. Even after that, the total value of the estate is about Rs.4,000 crore, said a High Court source.

The British government took good care of the Shovabazar property during its rule. It spent money from its coffers to collect tax from occupants and keep encroachers away. Even after independence, the government spent huge amounts for the upkeep of the property. After the partition, however, the land in East Pakistan was out of bounds to the India government. When Bangladesh was formed, prime minister Mujibur Rahman declared Shovabazar royal property as enemy property (under Vested Property Act). The property, about 97,000 acres, is now known as Gangamandal.

It is still an unsettled argument among legal experts why the British judges in Calcutta High Court could not resolve the case. Bhagwati Prasad Banerjee, a retired judge of Calcutta High Court, said it could be because Britain faced a legal logjam after World War I owing to its vast colonies. A backlog of cases was created in India also as the British gave little importance to quick disposal of cases then. “However, in the fifties, the English realised that the legal logjam could hit their country’s growth. So they took decisive steps and liquidated long-running cases every week. In India, we never took such steps due to resistance from lawyers and a section of judges,” he said.

Krishnanda Mukherjee, the current receiver of the Shovabazar royal property, however, begged to differ. “There have been major differences within the royal family in the past which was the reason behind the continuance of the case even after independence,” he said. He, however, admitted that the case moved at a slow pace in the recent years. “That is what Indian judiciary is all about,” he said. “In fact, I had to spend a lot of time with this case which was not regular but continuous.”

Mukherjee was in favour of the property remaining in the government's custody. “It is better the High Court looks after the property as it is of national importance,” he said.

The royal family, however, has no kind words for the receiver administration. “The receivers did nothing all these years,” said Deb. “They did not collect taxes on time from occupants. Also, they were supposed to give us a part of the income from property. But they did not give that saying the properties did not earn much these days. Also, like the British receivers did, the receivers should look for fresh encroachments and evict them. The family must be paid a part of the income as annuity as our forefathers left this property for us.”

Tracing the family members, however, would not be an easy job. The family does not have a list of the living descendants. Around 200 of them still live in the Shovabazar palaces. “At least they should pay the people who are looking after the deities and living in the houses of the royal family,” said Deb.

Receiver Mukherjee does not see an end to the Shovabazar case anytime soon and calls it an “irreconcilable dispute”. But the royal family is unfazed and is willing to do whatever it takes to continue the battle. “Our family will not leave it. They will fight for it even for another 100 years,” said Tirthankar.

The royal family stands united not to withdraw from the case. “Our forefathers fought for it so hard,” said Deb. “We want our forefathers' properties back because they won it from British India. What they won how could we lose?”