Anita Ghai loves shopping around for earrings and bindis, eating spicy chaat on the roadside and going for the latest movie. What would be a routine outing for most other city-dwellers, however, is an arduous journey that requires to factor in several considerations for her—the elevation of the shop on the pavement, availability of someone to help get on to the seat in the cinema hall and even the quantity of the beverage to drink in case an attendant is not there to help her to the washroom.

“There are times when I go without drinking water for hours because I don’t know if a washroom is available at a place and I’m able to use it,” says Ghai, 57. Online shopping sites are a boon, she says, and it is easier to get around in malls than in an open market. “But even there you need assistance to access the elevator or stairs, and I always have to sit in the front row in the theatre,” she says.

A highly regarded professor and academic, Ghai has been teaching and battling for disability rights for three decades. Polio crippled her at a young age. In 1980, at the age of 22, she tried for the civil services but was turned down because of her condition. Over the years she had two open-heart surgeries and in 2005 she survived breast cancer. She uses a motorised wheelchair to get around her ground-floor house in Rajouri Garden in West Delhi. She used to drive till the cancer was detected—she still keeps her old Maruti Zen. Now the family driver takes her in the family car to and from Ambedkar University Delhi, where she teaches in the department of human studies. “I was with Jesus and Mary College for a long time. I now teach two classes from 11am to 1pm at Ambedkar,” she says, offering to make me a cup of tea.

The wall of the corridor to her spick-and-span open kitchen has a large collection of family photos. When darkness falls, Ghai first switches on a light that falls on her late father’s photograph as an emotional ritual. “He was a great source of strength and support,” she says. “People would say things like ‘given her condition, why don’t you make a poor man your son-in-law’, but he refused. Eventually I became financially independent. Marriage didn’t happen. My grandmother would joke, ‘marriage can be hell, do you really want to get into it?’”

Delhi does not make things any better for Ghai or people like her. “There is barely any public park or hospital that is disabled-friendly,” she says. “Dilli Haat, India International Centre and India Habitat Centre are a few exceptions. I used to enjoy watching plays at Kamani Auditorium and Shri Ram Centre but have stopped going since it is not easy negotiating my way around. The Metro is supposed to be disabled-friendly but it loses out on the lack of last-mile connectivity. I haven’t been to a railway station in 15 years for this reason. It took more than 20 years for my earlier college to get a ramp. Also, you end up losing relationships. Most of my friends don’t live on ground-floor homes and many don’t have lifts.”

She wishes architects take more care. “Architecture emphasises more on aesthetics of a structure; there is nothing for bodies who can’t access,” she says.

What about people’s attitude? “Some people stare, some see me as an inspiration because I’m mobile,” she says. “What is disturbing is when someone wants to touch your wheelchair out of intrigue. They don’t realise it’s an extension of my body! It feels uncomfortable.”

In the kitchen, most things are at her eye level, from the stove to the wash basin and water filter. Fortunately for Ghai, her mother and two brothers live with their families in the house opposite to hers. She has a driver, a part-time cook and a cleaner, and she manages to lead a fairly self-contained existence. “Whether disabled or not, no one can be totally independent. We are all inter-dependent on each other, whether family, friends or society,” she says.

Ghai doubts if token gestures will make any difference in the lives of people like her. That is why she does not see much into Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s call to address the disabled as divyang (divine body) instead of viklang (disabled) in his Mann Ki Baat last December. “Where will you get divyashakti (divine power) if you don’t have infrastructure? I realise I’m one of the few fortunate ones who have a home, can afford a motorised wheelchair made in America.... I used to work in the slums of Jahangirpuri. There are disabled people there, too, living in the narrow lanes. How do you plan the city? In New York I could easily visit the Statue of Liberty. In Delhi I can’t even think of going to the Qutb Minar,” she says.

She had a horrible experience at the airport recently when she travelled from Dehradun to Delhi. Her wheelchair didn’t arrive in time and she was made to crawl on the tarmac. “It was undignified and humiliating,” she says.

At the university, Ghai wheels herself up the ramp, and her students help set up the laptop for her. She thinks movies are a great medium to sensitise people. “We’ve seen Barfi, Black, Wazir, Paa in recent times. We have always had some depiction of disability in our cinema, like Rajendra Kumar would always go blind... Or Barfi was about autism and deafness. But they mostly create sympathy or fear, not empathy. Popular media is an important way to create awareness,” she says.

Ghai points out that disability doesn’t differentiate between caste, religion, gender, age or nationality. “Anyone can have an accident or get afflicted with something that hinders her mobility or the senses. I don’t see it as a retribution for past sins, as some say. It is simply an existential condition,” she says.

On the campus, many a steep step to the washroom or a department has been smoothened into a small ramp. Besides Ghai, there is another wheelchair-bound professor and a few visually-challenged students in the university. Ghai’s office on campus has a small curio from a popular motivational poster designed by the British government in 1939 in preparation of World War II. As its popularity caught on, several of its parodies started circulating, making it a well-known meme over the years. This one is with the original message of the poster: ‘Keep calm and carry on’. She is doing just that.

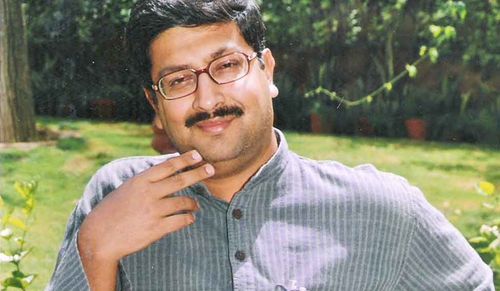

Interview/ Javed Abidi, director, National Centre for Promotion of Employment for Disabled People in India

Accessibility is the key to empowerment

How do you see the Accessible India campaign by the government?

I’m impressed with it. It is the first time someone has looked at accessibility in a big way. While it can be made better, it was the need of the hour. We have been saying for more than a decade that accessibility is the key to empowerment. Employment won’t be created out of thin air; the disabled must be skilled and educated in schools, colleges and universities. Right now it is limited to government buildings and they should put some pressure on the private sector, too. When I met Mukesh Jain [secretary at ministry of social justice and empowerment], who is leading the endeavour, he said first let’s make an example of it and then push the private sector.

Should design that allows accessibility for the disabled become a part of the architecture course?

Absolutely. If in the next two-three years, 2,500 buildings will be accessible assuming 100 per cent success rate, in the same period how many buildings will come up in the same cities which are hostile and inaccessible? From 1947 to 1995, we had the washout phase as far as disability was concerned with the exception of a little charity. From 1995 onwards, we pushed for the law that categorised public buildings and made transport accessible. We hadn’t thought of protecting the rights of disabled citizens earlier. From 1995 to 2015, how do we account for these 20 years? How many schools and colleges have come up that have accessibility for wheelchair users like me? In 2016, after ratifying the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, we now have a new law on the anvil. It’s a systemic issue. Enforce it firmly that all public spaces must be accessible. If the government is serious, we have the National Building Code, too. The message must go out. Besides taking care of the buildings, we should also look at policies.

What initiatives can be taken to sensitise people towards their disabled counterparts?

I have struggled with this question for the longest time. My challenge isn’t the common man; there is empathy in the general public, contrary to stereotypes. Stereotypes are more prevalent in families that think ‘now what will happen’. Parents can say study, get a job and the attitude changes. Problem is with policymakers and bureaucrats who don’t see disabled people as a vote bank. They might be well-meaning but when it comes to the crunch, it’s not a priority. There was nothing in any party’s manifesto for us till the 1990s. Farmers, women, caste, religion are all vote banks and that’s the bitter truth. The disabled have also failed to form into a collective, and even among us, there are divisions among the blind, deaf... there is no cross disability understanding in India. It was only from the 1990s that they were included in the census, allowed to take civil services exams, came under the right to education act.... I hope in the long run the 60-70 million people come together. Our milestones so far were because of allies in the media and judiciary.

Some people found the PM’s call on divyang versus viklang to be patronising.

He means well. Viklang has a negative connotation, divyang goes the other extreme. The rest is a debate. ‘Differently-abled’, ‘disabled’, ‘persons with disability’. The last one is the preferred term now since it implies, ‘people first, disability later’.