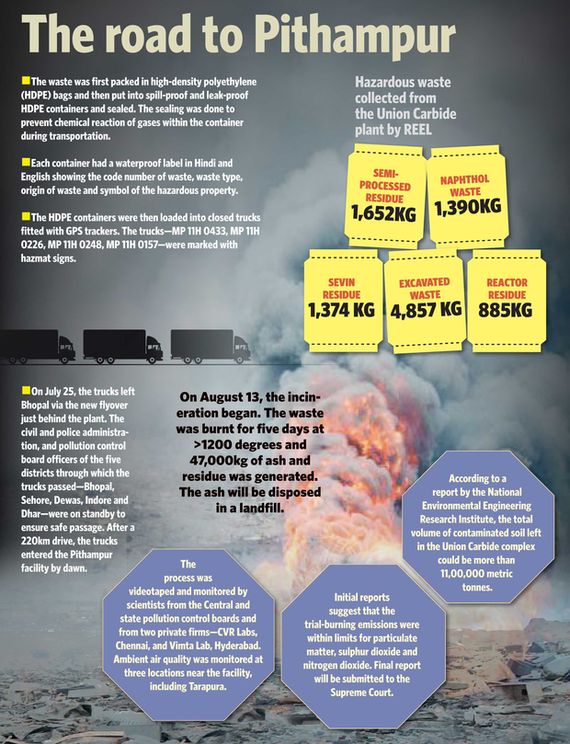

July 25. In the dead of night, four trucks drove out of the defunct Union Carbide plant in Bhopal carrying ten tonnes of toxic waste. Destination: an incinerator in Pithampur, near Indore.

The incinerator―technically, treatment-storage-disposal facility (TSDF)―is owned by Madhya Pradesh Waste Management Project, a division of Ramky Enviro Engineers Ltd (REEL). The consignment in the trucks was a sample from the 346 tonnes of waste left inside the Union Carbide plant, after it shut down following the 1984 Bhopal gas tragedy.

REEL quoted Rs.36 crore to dispose of the waste, and the Madhya Pradesh government awarded the contract to it. The sample of ten tonnes was incinerated to convince the Supreme Court that REEL’s process met emission standards. Scientists from the Central and state pollution control boards and from two private labs monitored the incineration.

But, the transportation of the sample and the subsequent incineration were kept a secret from the NGOs and gas victims who had been lobbying for decades for the safe disposal of the toxic waste. The transportation was done three days before schedule, with the full knowledge of the state administration (see graphics).

THE WEEK has correspondence, on the schedule advancement, between the state government and Arun Kumar Gupta, joint secretary, ministry of environment, forest and climate change. Sources said the operation was done hush-hush because Pithampur residents were opposing disposal of the waste in their village.

“The whole operation was kept under a veil of secrecy because the gas survivors’ organisations and the people of Pithampur are opposing the move to incinerate the waste in Madhya Pradesh. That, too, by a company which failed six times in the trial run of its incinerator,” said Rachna Dhingra, activist associated with Sambhavna Trust, an organisation for gas survivors.

Click here to read: The continuing tragedy

Earlier, the REEL facility had been fined by Madhya Pradesh Pollution Control Board, and its security deposit confiscated, for not meeting the norms for disposing hazardous wastes. It was even given notice for closure.

Graphics: N.V. Jose

Graphics: N.V. Jose

Once Pithampur residents came to know that the sample incineration was done, they upped the ante. Dr Hemant Kumar Hirode of Pithampur Bachao Samiti told THE WEEK that the residents would fast unto death if the remaining 336 tonnes of waste were brought to the village. Environmental organisations have approached the National Green Tribunal saying that the REEL facility is not equipped to process hazardous waste.

Even the Congress and the BJP have united to fight REEL. Dhar MLA Neena Verma is from the ruling BJP, but she raised the issue in the assembly, and the Congress supported her.

Toxic football After multiple studies showed that the toxic cesspool in Bhopal had to be cleared to prevent further contamination of soil and groundwater, the state government woke up and started looking for facilities. But, no one was willing to treat Union Carbide waste.

In July 2004, Alok Pratap Singh, a leader of gas victims, moved the Madhya Pradesh High Court seeking removal of toxic waste. (Alok died in a road accident in August 2015.) In June 2005, the High Court employed REEL to pack and store the hazardous waste lying inside the plant. REEL packed the waste and moved it to a Union Carbide warehouse, now in possession of the gas relief department of the MP government.

Satinath Sarangi, who has been fighting for the gas tragedy victims for decades, said, “The whole process of packaging was done with such callousness that more than 100 people from the neighbouring area had to be hospitalised over exposure to chemical dust.”

REEL identified 396 tones of toxic waste, of which 39 tonnes was lime sludge and 11 tonnes comprised “non-hazardous waste”. The remaining 346 tonnes comprised “tar, pesticides and intermediates”. The lime sludge was transported to REEL’s landfill site in Pithampur. That was when the protests started there.

In October 2006, a task force constituted by the High Court recommended that the bagged waste be sent to a facility owned by Bharuch Environmental Infrastructure Ltd in Ankleshwar, Gujarat. Initially, the Gujarat government green-lighted the move. But, it withdrew clearance after the residents of Ankleshwar protested.

On July 10, 2010, Union environment minister Jairam Ramesh visited Pithampur and apologised to the people for dumping the lime sludge there. It would happen no more, he said.

The state’s minister for environment and urban administration, who is today the finance minister, Jayant Malaiya, also said that toxic waste could not be dumped in Pithampur. Pithampur, he pointed out, was the catchment area of Yashwant Sagar Lake, which supplies drinking water to Indore town.

In June 2011, the Union government filed an affidavit before the High Court saying that the bagged waste could be sent to a Defence Research Development Organisation facility in Nagpur. Then, Nagpur residents opposed the move and the Vidarbha Environmental Action Group petitioned the Bombay High Court for a stay on the entry of toxic waste into Maharashtra.

In November 2011, the Maharashtra Pollution Control Board refused to give a no-objection certificate to the DRDO facility and it also stopped a facility in Tajola from incinerating a sample of the waste.

Click here to read: Survivors' saint

As the Union and state governments ran out of options, the ball rolled back to Pithampur on February 22, 2012. Around the same time, the German multinational GIZ offered to process the waste at its facility in Hamburg. It asked for Rs.25 crore, sources said.

The GIZ deal did not materialise even after six months of deliberations. Courts and governments had cleared the deal. Dhingra said, “The reason cited for termination of the offer by GIZ was ‘protest in Germany’. But the real reason was disputes over kickbacks.”

So, finally, on August 13, 2015, the ten-tonne sample was burnt at Pithampur. Sources in MP Pollution Control Board said the incineration was successful and the report of the process and monitoring of pollutants released would be presented before the Supreme Court.

In Pithampur THE WEEK put in multiple, futile requests to visit REEL’s 50-acre facility in Pithampur. Emails sent to REEL’s Hyderabad headquarters elicited no clear response. Eventually, this reporter turned up at the gates of the facility, but, as expected, was denied entry.

The facility was founded in 2006, but the road that leads to the main gate is still unsurfaced. The waste dumps are covered with tarpaulins weighed down with old tyres. Villagers said that during the rains the chemicals from the dump flowed downhill to Chirakhan village.

Kamil Mehar, a local environmentalist said, “Chirakhan suffers the most. Fields have become barren and the water is contaminated. Every house has had to invest in a water purifier.”

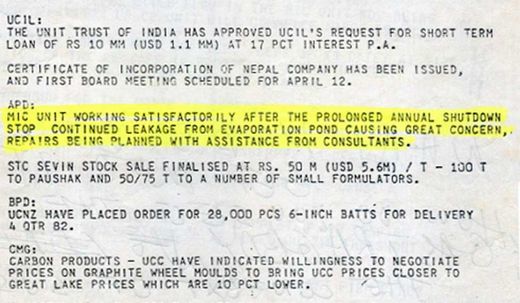

Leaked evidence: Excerpt from a 1982 telex sent by Union Carbide.

Leaked evidence: Excerpt from a 1982 telex sent by Union Carbide.

Tarapura village just outside the REEL facility suffers from exposure to toxic smoke and tainted water. Around half the villagers have skin and lung diseases. There are 200 houses in Tarapura. Hirode of Pithampur Bachao Samiti said, “People spend half of their income on health care.”

THE WEEK met Indra Bai, 52, who has developed a skin condition because of exposure to toxic water; Lakhan Singh, 56, and Shiv Narayan, 55, suffer from constant cough and stomach ailments. Subhash, who runs a tea stall, said he spent most of his income on health care as his wife and children had lung diseases. Chaman Chopda’s worry is about his toddler daughter, Ruby. “She is not gaining weight, despite being treated for the last two years,” he said. Most children in the village are sickly.

Sunderlal Patharia, who owns two acres near the REEL unit, showed THE WEEK two bags of groundnuts hanging from the handlebars of his motorcycle. “I sowed more than a quintal and got this,” he said.

Shahabaz Khan, a former employee of REEL, said in a signed affidavit before the MP Pollution Control Board: “Waste which should be sent to a landfill after treatment is sent there without treatment. [REEL] charges its clients for the treatment, but everything is done merely on paper.”

Journalist Rajesh Johri said, “Empty containers of chemicals and other toxic liquids are sent here by industries for disposal. The guidelines say that these have to be compressed and sent to a landfill. But, REEL sells the containers to scrap dealers.”

The quality of landfills is also under question, said Mehar. “There are evident leakages in the landfill,” he said. A well on the Gopeshwar temple premises provides ample evidence of the contaminated groundwater.

Poisoned by water Sarangi, who was THE WEEK’s Man of the Year in 2010, said, “The clandestine disposal of toxic waste at Pithampur is just the tip of the iceberg.” The iceberg is the toxic waste lying in solar evaporation ponds in the Union Carbide complex.

In the past three decades, the chemicals have eaten through the substandard linings of the ponds and have contaminated the soil and groundwater, said Rashida Bi of Chingari Trust, which works with gas victims.

Kesri Singh was 27 when tragedy struck Bhopal. The 58-year-old lives in Atal-Ayub Nagar, just outside Union Carbide. He said, “First it was the gas, and then the contaminated water.” Ramesh Chandra Pathak, a retired police officer and gas victim, said, “The government has forgotten the ponds spread over 32 acres.”

It is not that the state government is unaware of these ponds. Babulal Gaur, current home minister, mediated between Union Carbide and protesting farmers in 1982. The farmers had gone to court saying that their cattle had died after drinking water poisoned by these ponds. Gaur, a lawyer and MLA, stepped in and effected an out-of-court settlement.

1982 was just a flashpoint. The poisoning issue was a regular hassle in the monsoons, when the ponds would overflow and poison the surface water in the area. Gaur became chief minister in 2004-2005, but did nothing to clear the ponds.

The ponds were built in 1977, when Union Carbide was producing Sevin, a pesticide. THE WEEK has copies of two telex messages sent by Union Carbide to its headquarters in the US in 1982 and 1983. One says the “continued leakage from evaporation pond is causing great concern.” The gas tragedy in 1984 took the focus off the ponds.

Relatively recent studies have showed that the soil around the ponds is contaminated to a depth of 4 metres to 8 metres. A joint study by the National Environmental Engineering Research Institute (NEERI) and the National Geophysical Research Institute (NGRI) in June 2010 confirmed the contamination and advocated appropriate remediation. The study highlighted the presence of hexachlorocyclohexane and mercury in groundwater.

Dhingra said, “According to the NEERI report, the total volume [of contaminated soil] could be more than 11,00,000 metric tonnes. We have been demanding a proper study of the whole issue by a non-partisan agency like the United Nations Environment Programme, but the [Central] government is not listening. UNEP has agreed to do the study, but they want a formal request from the Union government. We met Union Environment and Forests Minister Prakash Javadekar and asked him to write a letter, but he is noncommittal.”

A Greenpeace study found heavy concentration of carcinogens and heavy metals like mercury. In some places, mercury contamination was 20,000 times to 6 million times the expected level.

In 2013, the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE) took a fresh look at 15 studies conducted over 30 years to asses soil and water contamination around the Union Carbide plant. CSE’s opinion was that the ponds were contaminating the surface water and groundwater. Based on the analyses, CSE released an action plan on environmental remediation in and around the Union Carbide plant. Two major suggestions were to prevent runoff from the ponds during the monsoons, and collection of soil contaminated by mercury and other hazardous waste.

As a result of these studies, activists took up the cry for potable water to be supplied to localities around the plant. But, the affected people started getting piped municipal water only in 2014.

According to estimates made by NGOs, more than 2,000 children born in the immediate vicinity of the Union Carbide plant have deformities. The Chingari Trust runs a rehabilitation centre for children who are physically and mentally challenged. Around 500 children from 26 gas-affected localities are registered with the centre.

Chingari Trust has profiled 765 special kids born to gas victims or to those who drank contaminated water. An example is Shilandra Ahirwar, 4. His father, Jitendra Ahirwar, a machine operator, said that they had been staying in Kalyan Nagar for the past 12 years. “Initially, we did not know that the water we drank was contaminated,” he said. “Even when we came to know, we had no option but to stay there.”

It is a strange situation in Bhopal. The waste has nowhere to go to. The people have nowhere to go. And, neither waste nor people seem to matter to the Centre and the state.