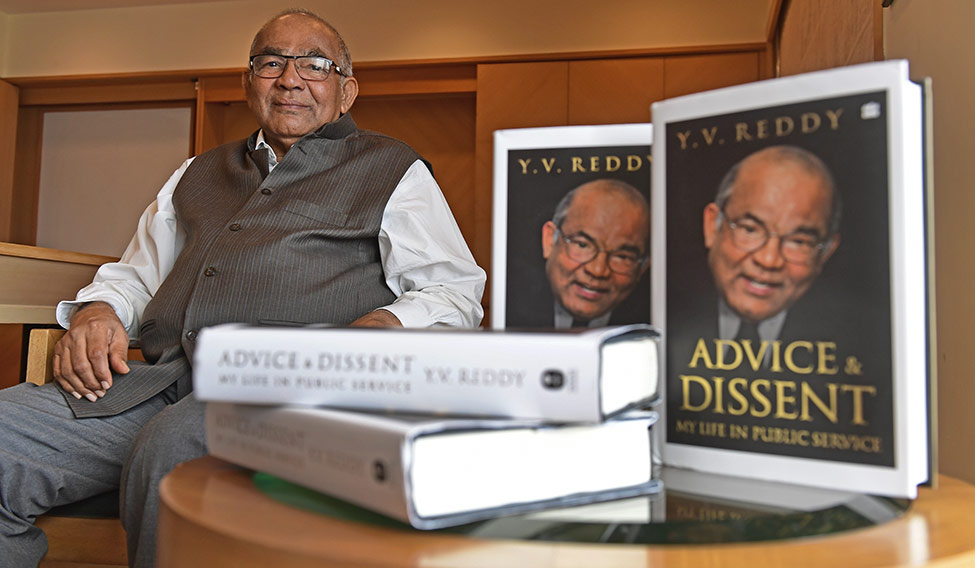

In his long career, Yaga Venugopal Reddy battled the worst of the crises and enjoyed the best of the good times. He was in the finance ministry when India faced the foreign exchange crisis in the early 1990s. He was the governor of the Reserve Bank of India from 2003 to 2008 when the economy grew in leaps and bounds. Reddy’s new book, Advice and Dissent: My Life in Public Service, which will be released on July 12, offers an insight into not just his career, but also his childhood and family. In an interview with THE WEEK, he talks about autonomy of Central banks, farm loan waivers and dealing with non-performing assets. Excerpts:

What was the thought behind the title ‘Advice & Dissent’?

It was an accident. The publishers and I had discussed many options; we couldn’t agree. The most preferred title from the publishers point of view was ‘Good as Gold’. So, he wanted to say the gold policy and whatever it is. I was very keen about ‘Destiny and Dharma’. I said, all of my life I went where my destiny took me and I did my dharma. But we couldn’t agree and we went round and round. Somewhere, this title was suggested and was agreeable. Not the first option, not even the second option, but acceptable to the publisher and me.

Talking of dissent, there is an instance when you even offered to resign over the issue of allowing foreign banks to acquire local banks. How did you finally get it your way?

Dissent should not be taken as defiance. There is a point of view. The government was legitimate in saying that it was a national commitment that we had to do. I was trying to convince. Many instances, I did not agree, but I said ok. Dissent yes, but you cannot defy. In this particular case, I felt so strongly that decision making was with the government; I felt that I would not put my heart and soul into the job. The government perhaps felt that if I was feeling [about it] so seriously, maybe there was some merit and maybe the government rightly felt perhaps it was a bit premature. And now, when I introspect, it appears that it was not an unwise decision.

How difficult is the tightrope walk of doing what a regulator must do but having political compulsions to meet?

The regulator or RBI is the creation of the government; it is given a mandate. The limited point is whether the government is sticking to the mandate. But, there is a lot of discretionary element that is of discussion and deliberation, and in a way, the RBI is given a trust of the people in money and finance. The government itself is saying it is autonomous. Therefore, if the RBI has to be effective, then it has to show that it is observing the objectives of the government.

In the recent times, the RBI’s autonomy has been questioned again.

The Central bank has been created by the government, and if it keeps agreeing with the government, it becomes superfluous. But, if it keeps disagreeing, it becomes obnoxious. So, it should be able to give a different point of view and also take a different view if necessary. My approach is that, in day-to-day matters, there should be operational autonomy. Even the current controversy should be seen in the context of changing approach. Only one thing I would say in the defence is that a lot of amendments that took place in the RBI Act up to 2008 strengthened the position of the RBI in the financial sector. And, almost all the amendments that took place after 2008 reduced the position of the Central bank.

Is this a dangerous trend being set?

I am not going into specifics, but these are the characteristics of what is happening.

You have raised issues over providing farm loan waivers. It happened during the Manmohan Singh government and it is a matter of debate today, too.

Fundamentally, in credit culture point of view, it doesn’t make sense. But, if there are broader social reasons, we can’t say anything much about it. The idea that farmer loan waivers are going to destroy the credit culture and fiscal position of India is overstating the problem. The amount of loans you are writing off for Air India or many of the private corporates where they have done restructuring, it goes into thousands of crores. So, morally you can’t say that it is a bigger problem than the other problems. There are a lot of people dependent on agriculture and agriculture is a risky business. But we are not solving the real problem, which is uncertainty of price, uncertainty of power supply, irrigation. So, in a way, we are not able to solve the real problems of the farmers, and we are only taking care of the credit problem.

Another important issue you have raised is related to non-performing assets, which has gone from bad to worse. Is it the regulator or the government who should find a solution? Shouldn’t it have been dealt with much earlier?

There are many reasons for NPAs. It is not simply a fraud or simply a policy; it may be macro policy or regulatory policy. I think some analysis has to be made to find out how much is the reason for what. I think that exercise is being done by the RBI. At the moment, you have NPAs on hand that have to be handled. Let us accept that, in the ultimate analysis, the moment you lend, all business will not succeed. Therefore, you have to take a more nuanced review of the NPAs. In the efforts now, the credit flow is being choked because of the NPA problem. As far as the stock problem is concerned, you are stuck with the problem. You have to find a solution, which doesn’t as far as possible compromise the credit flows.

Your career spans from working as a collector in Andhra Pradesh, to being in the finance ministry, the World Bank and the RBI. What was the best and most challenging time?

In my view, the best years were when I made some difference. It is not as governor. As a governor, I had a very good political leadership, economic leadership, deputy governors and professional staff. All I did was enable them to work. But it was as the joint secretary, balance of payments, in 1990-93, that was the most challenging. Three years there was a crisis. The whole nation could be put to shame. Political leadership was virtually a vacuum. In three years, there were three prime ministers, three finance ministers, three economic advisers, three governors. I had to brief the people whenever a new man came. It looked as if the whole thing was on me. The economists used to always take long-term solutions, I had to fix the immediate problem, without compromising.